Decentralised clinical trials are held in higher regard than their traditional counterparts when it comes to climate impact. That said, industry experts are challenging trial designers to take a deeper look into the sustainability of DCT practices

Words by Cheyenne Eugene

Decentralised clinical trials (DCTs) are the pharmaceutical industry’s answer to the traditional, often climate-unfriendly randomised control trial (RCT) model. There are plenty of positives to suggest that DCTs trump traditional trials in terms of sustainability, including removing the need for patients to travel to trial sites, but experts are still urging the industry to take a close look at their impact. Are the environmental benefits being undermined by ill-thought-out practices?

The tech and device footprint

A heavy question mark is lingering over the sustainability of DCTs due to the technology and devices that are involved in their execution. The beginning and end of a product’s life cycle is where much of the concern lies.

New tools are often manufactured for DCTs, but this process can cancel out any potential emission reductions. “If you provide a patient with a smartphone so that they can participate in a DCT,” says Jason LaRoche, Director, Janssen Clinical Innovation, “some 80% of the emissions generated lie with the manufacturing.” He adds that these emissions are the equivalent of participants attending “57 GP visits”, indicating a potential fault in the DCT model.

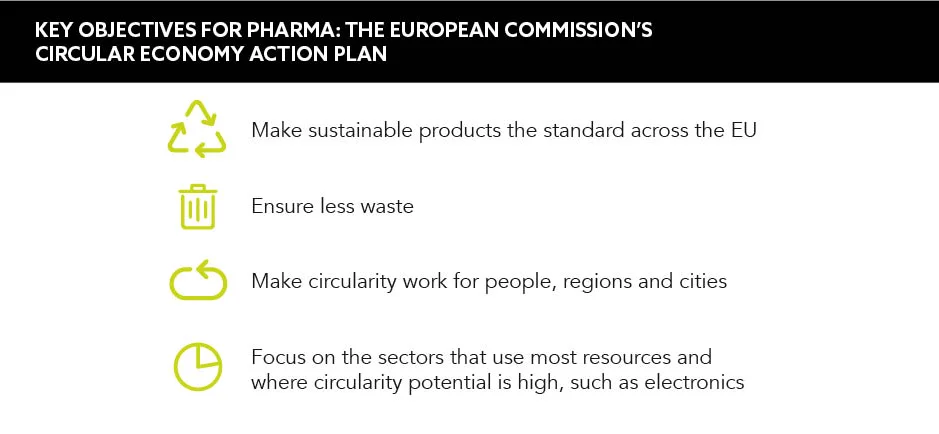

The end of a device’s life cycle also perturbs some experts as technology such as wearables come into close contact with patients and may hold a trace amount of a drug or biological material. This means that conventional recycling pathways are not always suitable. “It’s this unique contamination risk that prevents these types of devices from going down the traditional recycling route,” says LaRoche. As such, the default option for many of these devices is incineration, which has its own environmental consequences. “This is gaining the attention of regulators,” he continues. Earlier this year, for example, the European Commission presented its legislative proposals for fostering product circularity for digital health devices.

You can reduce the energy consumption of a process by simplifying it

Solutions must be developed to allow DCTs to reach their sustainability potential and alleviate emission concerns. One such solution is the ‘new software, same hardware’ approach, in which experts argue that pursuing software solutions that leverage existing devices and avoiding introducing new hardware is a viable solution. Manufacturers also need to actively design devices for circularity, allowing them to be cleaned, refurbished and reused. “Recycling [should] only be the last resort when we’ve fully depleted the device’s utility,” urges LaRoche. This grants maximum usage and minimal carbon footprint.

“Sustainability and carbon footprint questions do arise when wearables and other devices are used only or exclusively for the duration of the trial,” says Van Zyl Engelbrecht, Director of Clinical Operations, Lindus Health. He tells GOLD about an existing solution called ‘Bring Your Own Device’ or BYOD. Platforms that use BYOD principles are already being employed by Lindus Health, and they have led to no hardware waste within their studies – a solution that other pharma companies could benefit from harnessing, too, if they haven’t already.

Simplifying trial logistics

One of the great benefits of DCTs is that the trial is taken to the patient, meaning that their potential travel emissions are taken out of the equation. However, LaRoche warns: “Distribution and logistics, if not done right, could generate more emissions than the traditional model.” For example, as many trials include the need for at-home visits, a healthcare professional may have to travel just as far to reach the patient as the patient would travel to the trial site, or further. One potential solution put forward by Engelbrecht is to “design and develop DCT protocols that require at-home visits only when it is absolutely essential, cutting down [emissions] and logistical complexity”.

If you provide a patient with a smartphone so that they can participate in a DCT, 80% of the emissions generated lie with the manufacturing

When at-home check-ups are necessary, LaRoche suggests assigning HCPs who are based closer to the patient and combining multiple patient visits in one trip. “You’re maximising the number of patient visits you achieve compared with the amount of emissions that are generated from travel,” he highlights.

Finding sustainable suppliers

DCTs rely heavily on supply networks and potentially suspect suppliers that may not be prioritising sustainability. As environmental degradation impedes patient health, “DCT service providers should actively select suppliers that prioritise sustainability and lower the patient burden”, urges Engelbrecht. Unfortunately, this approach is not yet widely adopted within DCTs. If this isn’t addressed, “we will continue to see a reliance on suppliers that push for higher service fees to the detriment of sustainability”, Engelbrehct adds.

LaRoche therefore encourages sustainability to be established as a “pre-competitive space”. In short, the focus should be on the planet, not profits. Agreeing with Engelbrecht, LaRoche urges DCT providers to “start with the suppliers that are already thinking about sustainability, engage with them and amplify reductions while building knowledge and experience”.

Efficiency, efficiency, efficiency

If executed correctly, bids to improve clinical trial efficiency should always lead to hitting sustainable goals. “Emissions can be significantly lowered when clinical trials are designed to be as logistically efficient as possible,” notes Engelbrecht. All processes require energy, and this, directly or indirectly, involves the generation of emissions. “You can reduce the energy consumption of a process by simplifying it and reducing any transportation or movement of goods,” says LaRoche, emphasising that this is the formula for a more sustainable system. “Focus on efficiency and that’s going to help you reach the right outcome,” he concludes.

Ultimately, for the most sustainable DCT practices, the principles of reduce, reuse, recycle; simplified logistics; and finding partners with mutual respect for the mission are crucial. DCTs have the potential to be greener than the traditional RCT, but pharma must avoid falling into the plentiful potholes. These solutions are just the tip of the iceberg and could spell a triple win for pharma, the environment and patient health.