AI has deep roots in science fiction. Traditionally painted as a power-hungry monster, it is understandable that people have tended to mistrust these algorithmic machines. Far from being Frankenstein’s creation, however, AI could be set to revolutionise drug discovery

Words by Jade Williams

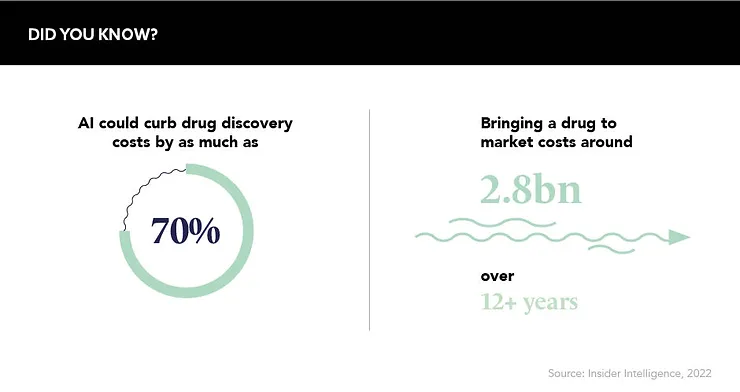

Increasingly more pharmaceutical companies are investing in artificial intelligence technology to save time, money and manpower during the many phases of R&D. Bids to develop new drugs can result in failure rates of 96%, leading to the high costs associated with bringing these to market. As a result, increasing efficiencies and accuracy are major considerations. According to a new report by Research and Markets, the use of AI in drug discovery has a projected market value of $9,293m by 2031 – undoubtedly impressive, but a question remains as to whether AI is the answer to pharma’s drug development problems.

Decisions, decisions

Adopting AI in pre-clinical stages involves implementing tools to read and analyse existing data and literature to find similar molecules and pathways that have previously launched successfully, thus finding drug candidates for potential development pathways.

“A lot of people like to think of drug discovery as being a cycle in which you design a molecule which then gets manufactured,” notes Allan Jordan, Vice President and Director, Oncology Drug Discovery, Sygnature Discovery. “AI is actually just about speeding up the design and discovery process, so it’s a way of accelerating the progression.”

Artificial intelligence is actually just about speeding up the design and discovery process

As well as speed, efficiency and accuracy are also key benefits in terms of decision making and modelling. “AI undertakes that data analysis, it generates a predictive model to suggest a series of hypotheses, those hypotheses are tested in the lab and then that information is fed back to improve the model. That’s actually what chemists and drug discovery scientists have been doing for the past 50 years. It’s just the machine version,” explains Jordan. “It takes some of the thinking away and allows you to think about more factors at any one time than you would be able to do as just a person.”

Using AI in this way also means that a mass of manual labour is freed up for other tasks within those initial research stages. Without AI, Jordan comments that researchers can “analyse three, maybe four different pieces of data at any one time around a particular hypothesis”, whereas “machines can handle 20 to 40 different variables”. Not only does AI accelerate the speed of drug development, but it can carry out far more in-depth analysis than a manual team, allowing them to focus on the more intricate details of discovery, and the accuracy it brings has the potential to improve the probability of approval, too.

A poorly oiled machine?

The benefits of utilising AI platforms in early research stages are palpable, but Jordan conveys that the algorithms are not yet perfect. One of the main challenges is that an AI model and its output “is only as good as the data” and current AI models are “based on data from historical literature, and, as such, you often don’t really know what the machine is building this data on”, he explains. For example, AI cannot necessarily assist in research for first-in-class drugs as it has no historical data to build upon.

Automation and AI does not replace human evaluation

As is the case with human operators, mistakes can also occur. An example of this was seen in a pneumonia screening study entitled ‘Variable generalization performance of a deep learning model to detect pneumonia in chest radiographs’, in which the AI image recognition was flagging patients based on where the images were taken, not on the image results themselves. Images taken in one hospital were deduced by the algorithm to show pneumonia simply based on the location, which could have led to false diagnoses. Image recognition procedures, and, as an extension, AI, still needs fine tuning before it can be seamlessly integrated into pharmaceutical processes.

Working hand in hand

The fear of AI, no matter its benefits and pitfalls, is still prevalent. The concept of the AI overlord has taken centre stage for decades, preying on human fears of becoming not only subservient but second best to algorithms. If AI can carry out human tasks better than humans themselves, then where does that leave us in a future society?

Pav Rishiraj, Director and Head of Pharmacovigilance, Ipsen, alleviates some of these fears. “Automation and AI do not replace human evaluation,” he says. “Human participation and contribution are still required to evaluate insights and decisions to the welfare of those whom we serve.” And this leaves ample space for human input in the rapidly-approaching automated future.

Jordan argues that the public experienced the same fears of obsoletion at the introduction of computers into daily routines, however, “tools don’t necessarily replace people, but augment what we are able to do in a certain amount of time”. One day, AI algorithms may be discovering first-in-class drugs at scale, for example, but the technology will surely always need humans to pick up the baton and carry the drug through from development to market.

Working side by side with AI could become the next normal, but for now, it is playing a valuable role in assisting discovery. As Jordan states: “AI is just a tool among the toolbox of things used to discover drugs.” Pharma companies should grasp hold of AI when seeking to streamline their drug discovery processes. The work of humans is unlikely to ever be outshone by machines, but together they could discover things the world could never expect.