Abstract

Over the last decade, intravitreal anti-vascular endothelial growth factor (anti-VEGF) agents have been increasingly used in the management of various retinal diseases, especially diabetic macular oedema. Diabetic macular oedema is one of the leading causes of legal blindness among patients with diabetic retinopathy, meaning these patients are eligible for associated medical benefits. It is essential that diabetic macular oedema is managed with an effective and safe treatment for good long-term prognosis. Over the past decade, focal/grid laser photocoagulation has been the gold standard treatment. However, evidence supporting the superior clinical benefits and relative safety of anti-VEGF agents has driven a recent shift in treatment paradigm, favouring anti-VEGF over laser treatment. Previous studies involving systemic anti-VEGF treatment in cancers have identified an associated increased risk of arteriothrombotic events, such as myocardial infarction and stroke, which are potentially fatal. Hence, it is important to evaluate whether such risks, which will significantly alter the safety profile, persist with intravitreal administration. A comprehensive literature review was performed and concluded that no significant increase in risk of ocular or non-ocular adverse events, particularly arteriothrombotic events, were associated with anti-VEGF agents, predicting an overall favourable safety profile. A summary of some of the possible adverse events recorded in the various studies, albeit at relatively low rates, are also included. Additionally, it is briefly discussed how real-world concerns of cost and affordability can influence treatment choice, thereby affecting how clinical evidence is transferred into practice.

INTRODUCTION

Over the last decade, intravitreal anti-vascular endothelial growth factor (anti-VEGF) agents have been increasingly used in the management of various retinal diseases, especially diabetic macular oedema (DMO). DMO is one of the leading causes of legal blindness among patients with diabetic retinopathy, meaning these patients are eligible for associated medical benefits.1 Hence, choosing an effective and safe treatment is crucial for long-term prognosis. Over the past decade, focal/grid laser photocoagulation (hereafter referred to as ‘laser’) has been the gold standard treatment for DMO. Recent evidence from multiple trials reporting the superior clinical benefits and relative safety2 of anti-VEGF agents has driven a shift in the treatment paradigm towards their usage. In terms of safety, previous studies involving systemic anti-VEGF treatment in cancers have identified an associated increased risk of arteriothrombotic events (ATE), such as myocardial infarction (MI) and stroke,3 that are potentially fatal. Consequently, the ocular and systemic safety profile of intravitreal anti-VEGF agents should be well evaluated to determine if they are safer compared to other available treatments for DMO. An example is intravitreal corticosteroid injections or implants, which are effective but associated with increased risks of elevated intraocular pressure (IOP) and premature cataracts.4,5 The efficacy of anti-VEGF agents is presented elsewhere;6 hence, this review discusses the safety profile and real-world cost concerns of anti-VEGF therapy to aid the selection of treatment.

METHODS

Using Medline, PubMed, and Cochrane databases, a comprehensive literature review was performed to identify relevant studies on anti-VEGF treatment in DMO. Search terms included anti-VEGF, bevacizumab, ranibizumab, aflibercept, trap-eye, pegaptanib, diabetic macular edema, effectiveness, efficacy, safety, and cost. Studies published in English from 2004–2016 were selected, after reading their abstracts and full-texts, to include seminal papers and landmark trials. Eventually, 52 studies were collated, comprising 26 clinical trials, 3 systematic reviews, 20 review articles, 2 retrospective studies, and 1 case series/report.

A BRIEF HISTORY OF INTRAVITREAL ANTI-VASCULAR ENDOTHELIAL GROWTH FACTOR USE

The use of intravitreal anti-VEGF for treatment of ocular neovascularisation arose when studies identified the pivotal role VEGF had in the pathogenesis of wet age-related macular degeneration (AMD). Trials testing pegaptanib (anti-VEGF) in patients with wet AMD demonstrated a safe reduction in the associated visual loss, resulting in US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approval in late 2004.7 This marked the first approval of an anti-VEGF for the treatment of a disease due to ocular neovascularisation.7

In early 2004, bevacizumab (BVZ) was the first anti-VEGF to be FDA approved for the systemic treatment of colon cancer, following successful trials. Yet, there were concerns over BVZ structure, diminishing the drug properties of penetration, efficacy, and safety during intravitreal use.8 This led to ranibizumab (RBZ), a small truncated variant of BVZ, being created. Contrary to these concerns, off-label use of intravitreal BVZ proved to be effective too,7 although the treatment was never approved by the FDA for intraocular use. Instead, it was the smaller molecule, RBZ, which attained FDA approval in 2006, following pegaptanib, for the treatment of wet AMD after large trials proved its efficacy and safety.7

Aflibercept was marketed as an alternative agent, with a lower dosing frequency and better pharmacokinetics of VEGF binding; compared to RBZ or BVZ, the VEGF binding affinity of aflibercept is 100-fold stronger. Results from these trials demonstrated non-inferiority, despite its lower dosing frequency, culminating in aflibercept approval by the FDA in 2011.7 A comparison between the molecular properties of the four anti-VEGF agents has previously been summarised.6

PATHOGENESIS OF DIABETIC MACULAR OEDEMA

In diabetes, pathophysiological mechanisms such as synthesis of advanced glycation end-products and protein kinase C activation contribute to many diabetes-related microvascular complications,9 including DMO. These biochemical abnormalities cause intracellular hypoxia and increased VEGF expression,10 resulting in an imbalance of pro-angiogenic and normally expressed VEGF-A isoforms. Several other growth factors and inflammatory mediators also contribute to the pathogenic process of DMO, leading to breakdown of the blood-retinal barrier.11 Consequently, retinal vascular permeability increases and plasma proteins leak into the neural interstitium, resulting in an oedematous retinal layer. This affects visual processing and thereby visual acuity. Intravitreal anti-VEGF therapy achieves its therapeutic effect by downregulating circulating VEGF, a critical molecule in the angiogenesis and inflammatory processes that occur in DMO.3,11 Hence, it is possible that consequent lower levels of VEGF may interfere with its normal physiological role of stimulating vasculogenesis and angiogenesis in hypoxic conditions, resulting in an increased risk of systemic adverse events (AE), such as ATE and hypertension,3 which have been reported with systemic anti-VEGF use. Currently, four intravitreal anti-VEGF agents are available to treat DMO: namely, RBZ, BVZ, aflibercept, and pegaptanib. Herein, we discuss their safety profiles with a focus on landmark trials.

SAFETY OF ANTI-VASCULAR ENDOTHELIAL GROWTH FACTOR AGENTS

Ranibizumab

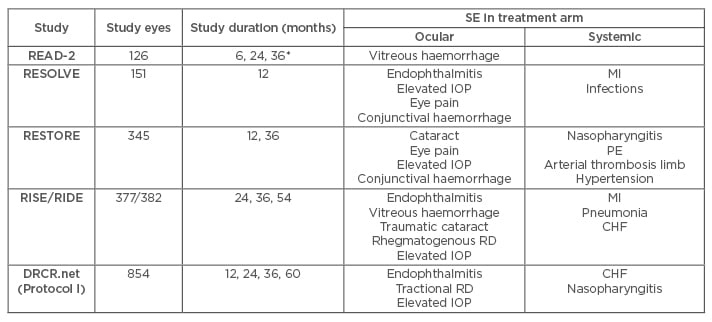

RBZ (Lucentis™, Genentech, Francisco, California, USA; Roche™, Basel, Switzerland) is a recombinant, humanised, monoclonal antibody fragment that has only antigen binding domains specific to all isoforms of VEGF-A. It is approved by the FDA and European Medicines Agency (EMA) for the treatment of AMD, retinal vein occlusion, and diabetic retinopathy. Among the four agents, RBZ is well-studied with extensive Level I evidence supporting its efficacy and safety.9 We reviewed and summarised its safety profile in Table 1, based on five important randomised controlled trials (RCT). Additionally, DRCR.net (Protocol T), which compares the relative safety of RBZ and two other anti-VEGF agents in patients with DMO, will be discussed separately.

Table 1: Summary of adverse events with ranibizumab treatment in DMO patients in RCT.

*Safety data was only reported at 6-month intervals in READ-2.

CHF: congestive heart failure; DMO: diabetic macular oedema; IOP: intraocular pressure; MI: myocardial infarction; PE: pulmonary embolism; RCT: randomised clinical trial; RD: retinal detachment; SE: side effects.

READ-2

This clinical trial was a Phase II, 14-site, investigator-initiated study that randomised 126 patients into three groups (0.5 mg RBZ, laser, and combination of RBZ with laser) and reported results at three intervals (6, 24, and 36 months); however, safety data were only reported at the 6-month interval. Systemically, one death from stroke occurred in the combination arm, but was judged to be unrelated to RBZ treatment. Notably, vitreous haemorrhage occurred in all three arms with no significant difference in incidence.12

RESOLVE

RESOLVE, a Phase II, multicentre, sham-controlled trial studying the effects of two doses of RBZ (0.3 mg and 0.5 mg) against placebo in 151 patients, found no significant differences in the incidence of ocular and systemic serious AE (SAE) or AE between RBZ and sham. However, an episode of MI (1%) within the study group was suspected to be related to RBZ. Also, two RBZ-treated patients (2%) were discontinued due to endophthalmitis. Common ocular AE reported included conjunctival haemorrhage, elevated IOP, and eye pain.13

RESTORE

RESTORE was a Phase III, multicentre (across 13 countries) trial that studied efficacy and safety of 0.5 mg RBZ against laser only and RBZ combination with laser, and involved 345 patients assessed over a 12 to 36-month period. In terms of ocular SAE, cataract was most common with no statistically significant difference between groups, while endophthalmitis did not occur. Several non-ocular SAE were suspected, including pulmonary embolism and arterial thrombosis in the limb. Overall, there were 14 deaths over 3 years, but none were related to RBZ or the procedure. Common ocular AE included eye pain, while reported non-ocular AE included nasopharyngitis.14,15

RISE/RIDE

RISE/RIDE were two parallel, methodologically identical, Phase III, multicentre trials that compared the efficacy and safety of RBZ with sham at 2, 3, and 5-year intervals by randomising patients into three groups (0.3 mg RBZ, 0.5 mg RBZ, or sham injections). RBZ was generally safe over 5 years, with relatively low rates of ocular and non-ocular AE. Ocular SAE were uncommon but included vitreous haemorrhage, endophthalmitis, and traumatic cataract. Common ocular AE reported were similar to those in the aforementioned trials. Systemically, the most common SAE were MI and congestive heart failure, but these events were related to the disease rather than RBZ. Additionally, the incidence of Anti-Platelet Trialists’ Collaboration (APTC) events at 24 months in all RBZ-treated patients was 2.4–8.8% (versus 4.9% [RISE] and 5.5% [RIDE] in sham). Despite this difference in incidence between RBZ and control, no associated increase in risk was found.16-18

DRCR.net (Protocol I)

This study was designed to compare both RBZ and intravitreal steroid treatment against laser over 5 years at four intervals (1, 2, 3, and 5 years). Of relevance, there were no associated differences in systemic or ocular events between RBZ-treated eyes and control over the 5-year period. Systemically, in terms of APTC events, lower rates were observed in the RBZ group than sham group. Locally, the 5-year safety data reported four cases of endophthalmitis in RBZ-treated patients, which was not significantly different from laser-treated patients.19-22

Bevacizumab

BVZ (Avastin™, Genentech; Roche™) is a recombinant, humanised, full-length monoclonal antibody that binds the same targets as RBZ, since both are derived from the same parent mouse antibody. Unlike RBZ, BVZ is licensed for the treatment of several different cancers only in the USA and the European Union (EU). Despite this, off-label usage is common in the management of wet AMD and DMO.23

DRCR.net

This trial was the first Phase II, multicentre RCT comparing intravitreal BVZ treatment against laser in 109 DMO patients for 24 weeks. Its small sample size and short follow-up time limit its suitability for drawing conclusions regarding BVZ’s safety profile. Nonetheless, the safety data are still useful as an indication of some of the ocular and systemic AE or SAE that might be expected with BVZ treatment. In terms of ocular complications, a case of both endophthalmitis and transient elevated IOP was reported following BVZ. Additionally, although two cases of MI and three cases of hypertension occurred in the study group, the authors judged them to be unrelated to the study drug, because the involved patients had pre-existing comorbidities predisposing to susceptibility.24

BOLT

This study was a Phase II, single-centre RCT, designed to compare intravitreal BVZ and laser at 12 and 24-month endpoints among 80 patients. At 12 months, no cases of endophthalmitis or retinal detachment were reported with BVZ treatment, while most ocular AE were ocular surface disturbances related to the injection procedure, including eye pain, watering, and subconjunctival haemorrhage. Although evidence showed that BVZ was not associated with an increased risk for hypertension or ATE, it is worth noting that severe hypertension developed in one patient following BVZ treatment.25 Findings reported after 24 months were largely similar, with notable occurrence of one case of ocular hypertension (2.7%) and two cases of MI (5.4%). Nonetheless, no trends in systemic safety events related to BVZ were observed.26

PACORES

The PACORES study was a multicentre retrospective study that offers 5-year safety data, the longest available, on BVZ treatment in 201 patients with DMO (296 study eyes). Similar low rates of ocular and non-ocular SAE or AE were reported, consistent with other studies. Notable ocular complications included tractional retinal detachment (8 eyes; 2.7%), glaucoma (6 eyes; 2.0%), uveitis (4 eyes; 1.4%), rhegmatogenous retinal detachment (3 eyes; 1.0%), vitreous haemorrhage (2 eyes; 0.7%), and endophthalmitis (1 eye; 0.3%), while non-ocular complications included stroke (10 eyes; 3.4%), and MI (5 eyes; 1.7%).27

Aflibercept

Aflibercept (Eylea™, Regeneron, Tarrytown, New York, USA; formerly known as VEGF trap-eye) is a high affinity, recombinant fusion protein capable of binding multiple signal proteins involved in angiogenesis, specifically all isoforms of circulating VEGF-A, VEGF-B, and placental growth factor. It contains VEGF-binding domains of human VEGF receptors 1 and 2, fused to the Fc domain of human immunoglobulin-G1. Currently, aflibercept is licensed in the USA, EU, Japan, Switzerland, and Australia for several different vascular retinal diseases, including DMO.28

DA VINCI

DA VINCI was a multicentre, active-controlled RCT designed to compare four different aflibercept regimens to laser at 24 and 52-week intervals involving 221 patients. The most common ocular AE were 33 cases of conjunctival haemorrhage (18.9%), 17 cases of increased IOP (9.7%), and 15 cases of eye pain (8.6%). Two cases of endophthalmitis (1.1%), and one case of uveitis and retinal tear (0.6%) were reported with aflibercept treatment. However, no significant difference in the incidence of ocular SAE or AE was identified between aflibercept and laser. Notably, several cases of hypertension, MI, and cerebrovascular accident (CVA) occurred with aflibercept treatment, but were unlikely to be attributable to the study drug because all had significant underlying comorbidities that increased their cardiovascular risk.29 After 52 weeks, seven aflibercept-treated patients died, but this was unrelated to the study drug or procedures.30

VISTA/VIVID

VISTA (USA) and VIVID (Europe, Japan, Australia) are similarly designed Phase III, multicentre, active-controlled RCT comparing two aflibercept regimens to laser. Generally, the 52 and 100-week results were very similar, with similar incidences of ocular and non-ocular SAE or AE between aflibercept and laser. No cases of endophthalmitis were reported, while several cases of intraocular inflammation occurred. Additionally, there was no obvious trend in non-ocular serious AE, especially ATE, despite some slight imbalances in the incidence of various events between aflibercept and laser.31,32 Overall, the safety profile remained consistent after 148 weeks, with no new associated increased risk of any AE. Notably, three (0.5%) new cases of endophthalmitis occurred between 100 and 148 weeks in the original RBZ arms.33

Pegaptanib

Pegaptanib sodium (Macugen™, Eyetech™, New York City, New York, USA) is a ribonucleic acid aptamer licensed for wet AMD only in the USA and Europe.34 It specifically binds to the VEGF165 isoform to reduce ocular angiogenesis. Two main trials that studied pegaptanib in DMO patients produced results suggesting there was no significant difference in the incidence of AE between treatment and sham. Most ocular AE that occurred were mild-to-moderate, injection-procedure related, and expected. Notably, a case of endophthalmitis (0.8% per patient) was reported by Cunningham et al.,35 25 cases of increased IOP (17.4%) were reported by Sultan et al.,36 and no retinal detachment was reported. Systemically, no evidence of increased risk of ATE related to pegaptanib was noted, despite incidences of SAE like CVA/coronary artery disease/angina pectoris (1.40% each) and hypertension (0.07%).36

COMPARISON OF ANTI-VASCULAR ENDOTHELIAL GROWTH FACTOR AGENTS

DRCR.net (Protocol T) was the first and only RCT that published results directly comparing more than two different anti-VEGF agents, allowing us to understand their relative safety. This multicentre RCT was carried out over 2 years and randomised patients into three groups (0.3 mg RBZ, 1.25 mg BVZ, 2 mg aflibercept). Incidence of all AE over 2 years was similar across all groups except for APTC events, with incidence of 12%, 8%, and 5% in RBZ, BVZ, and aflibercept, respectively. Pairwise comparisons showed significant differences, which disappeared after accounting for potential baseline confounders, between RBZ and aflibercept only. Hence, caution should be taken to observe for APTC events when using RBZ.37

DISCUSSION

The shift in treatment paradigm from laser to intravitreal anti-VEGF as first-line therapy in DMO makes it paramount that they are safe with minimal side effects. Concerns over the safety profile of intravitreal use are understandable, considering how systemic usage is associated with an increased risk of ATE.3 Hence, it is essential that sufficient evidence shows that the risk of ATE is not increased with intravitreal anti-VEGF.

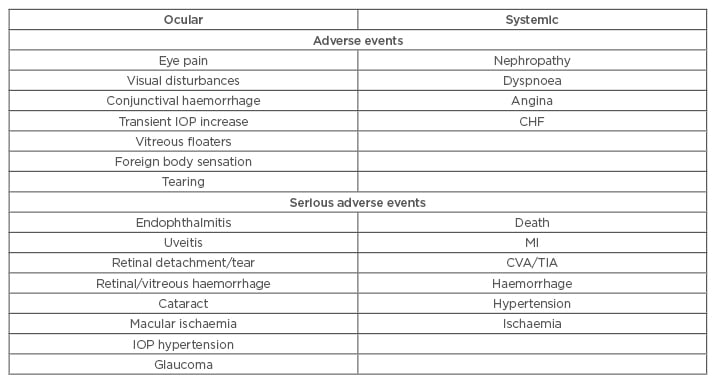

Overall, intravitreal anti-VEGF agents in DMO have been shown to be generally well-tolerated and safe,38 with a safety profile similar to results from trials evaluating their usage in other retinal diseases. No significant trend relating to the occurrence of ocular and non-ocular SAE or AE was specifically identified for any anti-VEGF agents. However, the caveat lies in that these trials are not powered to demonstrate safety, and more large-scale safety trials are needed before being certain about its safety. Table 2 shows a short summary of possible AE. Notably, most ocular AE are mild and injection-procedure related, making it possible to reduce occurrences by taking extra precaution during the procedure using aseptic technique for preparation and injection. This is particularly relevant to off-label BVZ use, as the need for individual repackaging/compounding makes sterile preparation especially crucial to avoid foreign body deposition, as described in a case report.39 Although systemic AE were reported, most are likely attributable to the patient’s pre-existing comorbidities. A meta-analysis by Avery et al.3 interestingly suggests that prolonged treatment with anti-VEGF might increase risk of CVA, vascular, and non-vascular death. Hence, precaution might be warranted when treating patients with significant cardiac and stroke history, or those with persistent DMO requiring repeated intravitreal anti-VEGF injections.

Table 2: Possible ocular and systemic, adverse, and serious adverse events with anti-VEGF as occurred across the RCT.

CHF: congestive heart failure; CVA: cerebrovascular accident; IOP: intraocular pressure; MI: myocardial infarction; RCT: randomised clinical trial; TIA: transient ischaemic attack; VEGF: vascular endothelial growth factor.

A Cochrane review also concluded that anti-VEGF agents are generally safe, apart from in high-risk patients, in whom their use still requires more research.2 Despite this, some differences do exist between individual agents as established in Protocol T, with results suggesting that aflibercept is relatively safer compared to the other two agents.37,40 However, this is not reflected in real life due to cost concerns. According to the 2015 American Society of Retina Specialists (ASRS) Preferences and Trends survey, BVZ is the most commonly used intravitreal anti-VEGF agent in the USA. Huge price differences exist between BVZ, RBZ, and aflibercept ($60, $1,170, and $1,850 per dose, respectively).41-44 Considering that diabetes maculopathy is a chronic disease and treatment of DMO requires multiple repeated injections, these cost differences can be significant. With raising medical costs and limited healthcare budgets, there is pressure on doctors to choose the most cost-effective option, especially in public-funded health systems. Several independent reviews have agreed that BVZ is indeed the most cost-effective option, even after using an analytical model to account for the raised concerns of increased risk of endophthalmitis or vascular complications.41

CONCLUSION

This review has consistently identified results across pivotal studies to support a favourable long-term safety profile among intravitreal anti-VEGF, with no significant increased risk of ATE. Though we agree that more large-scale safety trials are needed to be conclusive, doctors can still recommend anti-VEGF treatment to most patients, as clinical benefits of visual improvement and resolution of macular oedema outweigh the possible ocular risks. Notable cases where greater consideration should be given before starting anti-VEGF therapy include patients with significant comorbidities that increase their overall cardiovascular risk, as well as chronic persistent DMO. Lastly, besides considering the clinical evidence of efficacy and safety, cost practicality can be a huge influencing factor when choosing treatment in practice.