Authors: Reuven Zimlichman,1 *Elena Scotti,2 Giuseppe Plebani2

1. Harm Reduction Consultant, Director of the Institute for Quality in Medicine, Israeli Medical Association, Tel Aviv, Israel

2. PMI R&D, Philip Morris Products S.A., Quai Jeanrenaud 5, CH-2000 Neuchâtel, Switzerland

*Correspondence to [email protected]

Disclosure: All authors are employees of Philip Morris International.

Acknowledgements: The authors would like to thank Amanda Barrell, Brighton, UK, for medical writing assistance and Editage (www.editage.com) for providing English editorial support.

Support: Philip Morris International is the sole source of funding and sponsor of this research.

Received: 19.04.22

Accepted: 26.07.22

Keywords: Cardiovascular disease (CVD), heated tobacco, tobacco heating system (THS).

Citation: EMJ Cardiol. 2022;10[Suppl 6]:2-10. DOI/10.33590/emjcardiol/10124537. https://doi.org/10.33590/emjcardiol/10124537.

Abstract

Cigarette smoking is a major risk factor for the development of cardiovascular disease (CVD). Cigarette smoke contains toxicants that cross the alveolar barrier into the blood stream and elicit systemic oxidative stress and inflammatory responses, which can lead to an abnormal lipid profile and affect normal vascular functions. These changes predispose smokers to the development and progression of atherosclerosis, leading to various types of CVDs, such as ischaemic heart disease, cerebrovascular disease, peripheral artery disease, and aortic aneurysm. While the best choice a smoker can make is to stop smoking altogether, unfortunately not all smokers make that choice. In recent years, alternative products to cigarettes have been developed to offer a better alternative to continuing to smoke. However, new products representing a better alternative must be scientifically substantiated to understand how they present less risk to users compared with cigarettes. This literature review summarises the results of in vitro, in vivo, and clinical studies that, taken together, show the CVD risk reduction potential of switching from cigarette smoking to these smoke-free products.

INTRODUCTION

Cigarette smoking is one of the leading preventable causes of morbidity and mortality. Most of the smoking-related mortality results from atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (CVD), lung cancer, and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Since 1990, there has been only a slight decline in smoking prevalence. However, the number of smokers has plateaued in recent years. In 2019, an estimated 1.1 billion individuals smoked tobacco products worldwide, comprising 33% of men and 7% of women.1 In addition to morbidity and mortality, this population imposes a heavy burden on health services and significant health-related economic costs worldwide.

The cumulative duration of smoking is associated with the risk for coronary heart disease events, with a longer duration and higher number of cigarettes yielding a greater risk.2

The direct effect of smoking on the development of atherosclerosis is evident in numerous studies, including studies of patients using surrogate markers (i.e., intima-medial thickness) and autopsy studies that provide a direct pathologic demonstration of atherosclerotic plaques.3

BENEFITS OF SMOKING CESSATION

Smoking cessation can save millions of lives annually. It prolongs life expectancy by approximately 10 years, increases the individual’s quality of life, and is a major benefit for a healthy life.4

There is no question that smoking cessation is by far the best way to reduce the progression of CVD at any age. However, the cardiovascular benefits are perhaps less well-known and accepted amongst the public of various countries. Amongst individuals without known coronary heart disease, the reduction in the rate of cardiac events associated with smoking cessation ranges from 7% to 47%.5-7 The cardiac risk associated with cigarette smoking diminishes within a few years after smoking cessation and continues to fall over time.

In the original and offspring Framingham Heart Study, 8,770 individuals (including 5,308 ever smokers) were followed for a median of 26.4 years. The risk of a major adverse cardiovascular events (including CVD, death, myocardial infarction, stroke, and heart failure) was significantly lower within 5 years of quitting smoking (hazard ratio: 0.61; 95% confidence interval: 0.49–0.76) compared with active smokers.8 However, it takes at least 10 years, and perhaps up to 15 years, for the incidence rates of major adverse cardiovascular events in former smokers to approach those in never smokers.8 More intensive smoking cessation efforts have been more successful in achieving sustained abstinence and lowering future CVD risks.9

Despite these facts, a significant proportion of the adult population worldwide continues to smoke, and there has been little change in the prevalence of smoking since 1990.10 In both sexes, smoking rates are higher in less educated and poorer segments of the population.

Approximately 70% of cigarette smokers state that they would consider quitting smoking. However, despite knowing the harm caused by tobacco smoking, there are people who continue to do so. Multiple factors can influence why people continue to smoke, mainly habitual and psychological factors, pleasure, and nicotine addiction. For example, some individuals may be in psychological denial of the health risks and wish to continue enjoying the sensory and ritual experience of smoking.

Recent advances in science and technology have made it possible to develop innovative smoke-free products that could present less risk and are better alternatives to continued smoking. Smoke-free alternatives, such as heated tobacco products (HTP), heat tobacco without burning it, which produces significantly fewer and lower levels of toxicants compared with cigarette smoke.11,12 This is because the majority of harmful chemicals found in cigarette smoke and linked to smoking-related diseases are generated by tobacco combustion.13-17 These products provide a similar taste, ritual, and nicotine uptake as those of conventional cigarettes, providing smokers with better alternatives. There are different categories of smoke-free products, but the most widely used are e-cigarettes and HTPs.

SMOKING AND RISK OF CARDIOVASCULAR DISEASE

Harmful and potentially harmful constituents (HPHC)18 are generated at high levels by tobacco combustion.19 They include oxidising chemicals, acrolein, butadiene, metals (such as cadmium), polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons, particulates, and carbon monoxide (CO). HPHCs increase free radicals, lipid peroxidation, and contribute to several potential mechanisms of CVD, including oxidative stress and inflammation. These mechanisms, in turn, cause perturbations in biological networks linked to endothelial dysfunction, lipid metabolism, and platelet activation, leading to atherosclerotic plaque formation and an increased risk of CVD. These processes increase the risk for thrombosis and the rate of atherosclerotic progression in the arterial system.13

HEATED TOBACCO PRODUCTS VERSUS COMBUSTIBLE CIGARETTES: REDUCED LEVEL OF HARMFUL AND POTENTIAL HARMFUL CONSTITUENTS

HTPs are designed to generate a nicotine-containing aerosol by heating tobacco to temperatures sufficient to release nicotine and tobacco flavours but low enough to prevent burning of tobacco. Under the concept of heat-not-burn, heated, rather than burned, tobacco significantly reduces the levels of HPHCs generated, while retaining a satisfactory sensory experience for adult smokers who would otherwise continue to smoke. This of course needs to be substantiated on a product-by-product basis. The current review concentrates on the research results generated in relation to the tobacco heating system (THS; commercialised under the IQOSTM brand name) commercialised by Philip Morris International (PMI; New York City, New York, USA) in 2014.

Due to the absence of combustion, on average the levels of HPHCs in THS aerosol are reduced by >90% relative to cigarette smoke.12,20,21 Importantly, relative to smoke from a reference cigarette, the levels of International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC) Group 1 carcinogens are reduced by >95% in THS aerosol. This reduced exposure to HPHCs is evident across multiple in vitro and in vivo studies,12,22-37 where, compared with cigarette smoke, it demonstrates a significantly reduced biological impact. This also includes reduced perturbations in biological processes that lead to CVDs (e.g., oxidative stress, inflammation, and monocyte–endothelial cell interaction) and reduced monocyte adhesion to endothelial cells in vitro.28,38

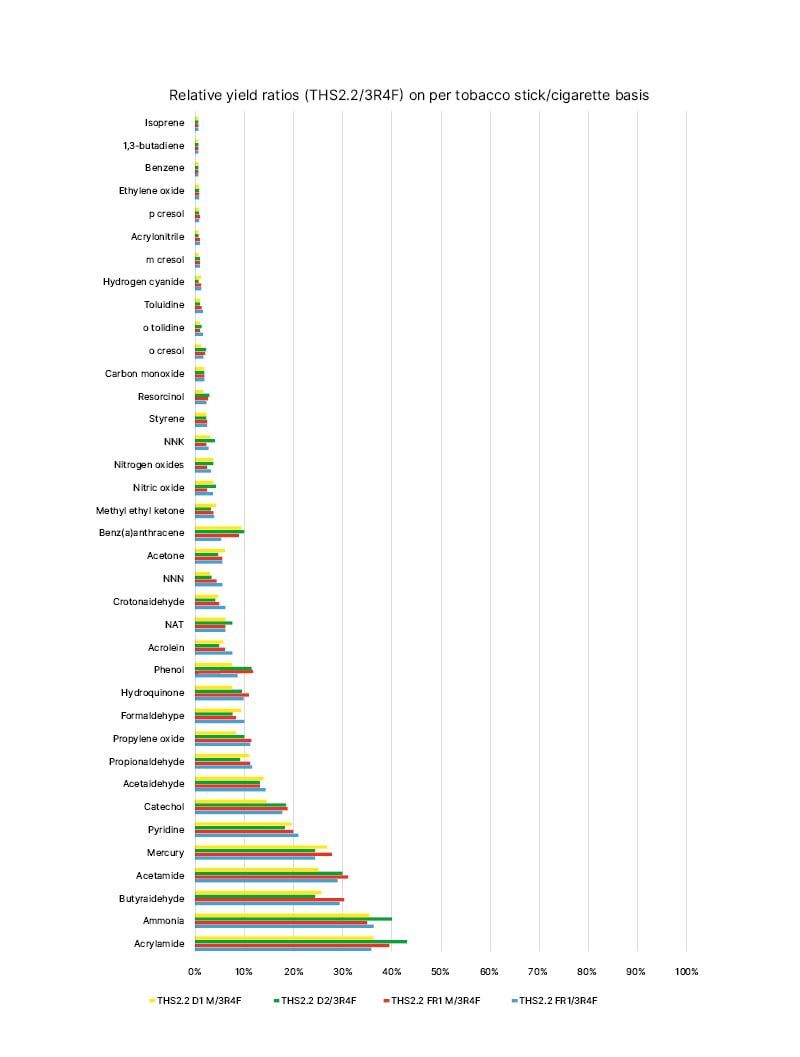

This HPHCs reduction in THS aerosol translates into a substantial reduction in exposure to toxic chemicals (Figure 1), as shown in animal and human studies. In fact, studies in mice have shown reduced exposure to harmful chemicals with both regular THS and the THS mentholated version.39,40

Figure 1: Mainstream aerosol harmful and potentially harmful constituents from the tobacco heating system compared with the mainstream smoke harmful and potentially harmful constituents from the 3R4F reference cigarette (constituent levels set at 100%) on a per-unit basis under the Health Canada (HC) intense machine-smoking regimen.

Four different tobacco stick variants were used for aerosol characterisation: two versions of the THS2.2 Regular (THS2.2 FR1 and THS2.2 D2) and two versions of the THS2.2 Menthol (THS2.2 FR1 M and THS2.2 D1 M).

NAT: N-nitrosoanatabine; NNK: nitrosamine ketone; NNN: N-nitrosonornicotine; THS: tobacco heating

system.

Figure republished from Schaller JP et al.12

HEATED TOBACCO PRODUCTS VERSUS COMBUSTIBLE CIGARETTES: CLINICAL EVIDENCE

Several clinical studies have validated this reduced exposure to HPHCs, including cardiovascular toxicants,41-43 even under conditions of concomitant cigarette use (of up to 30%).44

A series of randomised clinical trials were conducted by PMI in an ambulatory setting over a period of 3 months in Japanese and American smokers who switched from cigarettes to THS use.41,43,45,46 These studies defined the effects of reduced exposure to HPHCs after THS use on the human body. They showed that, after 5 days, the levels of 15 biomarkers of exposure to HPHCs linked to oxidative stress, inflammation, endothelial function, lipid metabolism, and platelet activation were substantially reduced in adults who switched completely to THS use and in a similar direction as that following smoking abstinence.

In a 6-month clinical study conducted by PMI in the USA, participants who predominantly used THS (≥70% THS use on average) experienced substantially reduced exposure to a broad range of HPHCs, while retaining the same nicotine exposure as those who continued smoking cigarettes. Given that the THS users also used cigarettes (~30% of use), the results are significant because they reflect the changes that can occur during the adoption and conversion phase for adult smokers in real-life settings.44

These reduced exposure results have also been validated by the findings of an independent study in healthy Japanese participants.47

HEATED TOBACCO PRODUCTS VERSUS COMBUSTIBLE CIGARETTES: EFFECTS ON SMOKING-RELATED CARDIOVASCULAR DISEASE

Preclinical and clinical studies have been conducted to assess whether reduced HPHC exposure could reduce the risk of developing smoking-related diseases. In in vivo studies, ApoE-/- mice initially exposed to cigarette smoke and subsequently switched to either THS aerosol or fresh air exposure showed very similar reductions in atherosclerotic plaque growth rates.48

The previously mentioned 6-month clinical study among smokers in the USA also examined whether switching to THS leads to favourable changes in biomarkers that reflect pathways involved in the development of smoking-related diseases.44 In this clinical trial, current adult smokers who switched to THS for the study duration showed improvement in clinical risk endpoints associated with CVDs, such as lipid metabolism, endothelial function, oxidative stress, and platelet function, in the same direction as that after smoking cessation (Figure 2). Switching to THS impacted lipid metabolism favourably, with significant increases in the levels of high-density lipoprotein cholesterol, and, similar to the impact of smoking cessation,49-51 oxidative stress and inflammation were reduced, as reflected by the significant reduction in white blood cells and 8-epi-PGF2α levels.52-54 Only slight changes were observed in vascular function (clotting, thrombosis, and endothelial function). In general, the trends of reduction in sICAM-1 and 11-TBX2 levels were more pronounced in the THS-use group compared with those in the dual-use group (that used both THS and cigarettes). These findings mirror the data reported following smoking cessation, in which individuals demonstrated a decrease in the levels of 11-TBX255 and sICAM-1. Altogether, the changes observed in this 6-month study indicate that completely switching from smoking cigarettes to THS use could have benefits from a CVD perspective, as indicated by the favourable changes observed in the clinical risk endpoints related to the main pathways underlying the development of CVD.

Figure 2: All eight primary clinical endpoints improved in smokers who switched to the tobacco heating system.44

Five of these eight endpoints (lung function, oxygen delivery, inflammation, carcinogenicity, and lipid metabolism) showed a statistically significant difference between people who switched to THS compared with those who continued smoking.

THS: tobacco heating system.

These findings are also supported by a clinical trial conducted by a research group at the Sapienza University of Rome, Italy. This crossover, randomised trial included 20 cigarette smokers allocated to different cycles of THS use, e-cigarette use, and conventional cigarette smoking. All participants used all the above products, with an intercycle washout of 1 week. The endpoints were oxidative stress, antioxidant reserve, platelet activation, flow-mediated dilation (FMD), blood pressure, and satisfaction scores.56 The study demonstrated that single use of e-cigarettes and THS (one product use per session) causes less detrimental acute changes than cigarette smoking in clinical markers involved in the development of smoking-related CVD (including oxidative stress, platelet activation, FMD, and blood pressure).

Another recent independent clinical trial on the effects of THS use on several cardiovascular parameters aimed to evaluate the effects of THS on vascular function, myocardial deformation, and ventriculo-arterial coupling in 75 current adult smokers without CVD.57 In the acute study, 50 smokers were randomised into groups who either smoked a single cigarette or used THS and, after 1 hour, crossed over to the alternate group. For the chronic phase, 50 smokers switched to HTP and were compared with an external group of 25 cigarette smokers before and after 1 month of HTP use. The acute and chronic studies both evaluated the following four parameters: exhaled CO level, pulse wave velocity, malondialdehyde level, and thromboxane B2 level. The chronic study also assessed global longitudinal strain, myocardial work index, wasted myocardial work, coronary flow reserve, total arterial compliance, and FMD. Acute THS use was associated with a smaller increase in pulse wave velocity, without any change in CO or biomarker levels, in contrast to cigarette smoking. In the chronic study, switching to THS improved the CO, FMD, coronary flow reserve, total arterial compliance, global longitudinal strain, wasted myocardial work, malondialdehyde, and thromboxane B2 values. The authors concluded that replacing cigarettes with HTP had a less detrimental effect on vascular and cardiac function than continuing to smoke cigarettes.

Independent reviews of the cardiovascular effects of HTP products have been published. In particular, a recent paper58 reviewed the potential impact of THS on CVD. Despite acknowledging that THS aerosol has a lower content of toxicants than cigarettes smoke, the authors underlined the cardiovascular effects observed in clinical trials with HTPs and highlighted the need for more data so health authorities could make fully informed decisions on the use of this category of products. However, the review did not mention that the magnitude of reduction of HPHCs is above 90%, and the authors did not cite important data from clinical trials where the biomarkers showed a positive evolution after switching to THS. Last but not least, the review mentioned that the effects on haemodynamic parameters observed in vivo and in clinical trials with THS use are well known to be nicotine effects.

Another HTP product has recently been shown to have beneficial effects on cardiovascular parameters, similar to THS.59 In a randomised controlled study conducted in the UK, healthy volunteer smokers were assigned to either continue smoking or switch to a HTP product. The study also included a control group of smokers who abstained from cigarette smoking. The aim of this study was to investigate whether biomarkers of exposure and of potential harm are modified when smokers switch from smoking cigarettes to exclusive use of a THP in an ambulatory setting. Various biomarkers related to oxidative stress, cardiovascular and respiratory disease, and cancer (such as total 4-[methylnitrosamino]-1-[3-pyridyl]-1-butanol level, 8-epi-PGF2α level, fractional concentration of exhaled nitric oxide, and white blood cell count) were assessed at baseline and up to 180 days. In continuing smokers, these biomarkers remained stable between baseline and Day 180. Conversely, in HTP users, the levels reduced significantly and became similar to those in the control group. This further corroborates the notion that the deleterious health impacts of cigarette smoking may be reduced in smokers who completely switch to using HTP.

CONCLUSION

In conclusion, a growing number of scientific studies have demonstrated that, relative to cigarette smoke, THS aerosol significantly reduces the effects on mechanisms that are causally linked to atherosclerotic plaque formation in human-derived in vitro systems. In addition, switching from cigarette smoke to THS aerosol exposure causes reduced atherosclerotic plaque growth in an animal model of disease. Importantly, the above referenced clinical data clearly show that switching from cigarette smoking to THS use results in favourable changes in clinical risk endpoints, which shift in the similar direction as they would upon smoking cessation.

As previously stated by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC),60 HTPs are not risk-free and they have not been scientifically demonstrated to help smokers quit. However, as demonstrated by industry-sponsored and independent research, switching to these products represents a potentially less harmful alternative for adults who would otherwise continue smoking.