Meeting Summary

A virtual symposium at the European Academy of Allergy and Clinical Immunology (EAACI) Digital Congress 2020 addressed breakthroughs in the understanding of the role of the IgE pathway in the inflammatory process, which leads to chronic spontaneous urticaria (CSU) symptoms, and discussed treatments that target this pathway. Two anti-IgE antibodies (omalizumab and ligelizumab) have distinct molecular properties and modes of action. Ligelizumab has an approximately 90-fold higher affinity for IgE than omalizumab, and inhibits the IgE/FcεRI pathway, which plays an important role in CSU. Adding to data presented during the symposium, several presentations throughout the congress reported data from a Phase IIb study and/or its extension. In this study, patients with moderate/severe CSU were randomised to receive ligelizumab 24, 72, 240 mg; omalizumab 300 mg; or placebo every 4 weeks (q4w) for 20 weeks. Complete hive control (weekly Hives Severity Score [HSS7]=0) was achieved by 30.2%, 44.0%, 51.2%, 42.4%, and 0.0% of patients, respectively, at 12 weeks. In severe CSU, weekly Urticaria Activity Score (UAS7=0) was achieved by 38.1% and 41.1% of patients on ligelizumab 72 and 240 mg, respectively, versus 20.0% on omalizumab 300 mg, increasing to 60.0% and 40.7% versus 34.4%, respectively, in moderate CSU. Among patients with baseline angioedema, those on ligelizumab achieved rapid and sustained weekly Angioedema Activity Score (AAS7), UAS7, and Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI) score improvements. Among patients who received omalizumab 300 mg in the core study followed by ligelizumab 240 mg in the 1-year extension, 30.2% achieved UAS7=0 after 12 weeks of omalizumab, but 43.4% achieved UAS7=0 after 12 weeks of ligelizumab. Lastly, the median time to loss of UAS7=0 during a treatment-free period after the core study was longest after ligelizumab 240 mg (10.5 weeks). Median time to loss of UAS7≤6 was also longest after ligelizumab 240 mg: 14.0 and 21.0 weeks after the core and extension, respectively. Ligelizumab is currently undergoing further investigation in Phase III studies.

Introduction

CSU is the sudden, spontaneous appearance of itchy wheals (hives), angioedema, or both in the absence of specific external stimuli, for >6 weeks.1 Worldwide, the prevalence of this debilitating disease is approximately 0.5–1.0%.2-4 CSU is associated with a significant burden, not only on the patients (in terms of daily activities, functioning, emotional and psychological distress, loss of energy, and disturbed sleep), but also on society (with impacts including loss of productivity, absence from work, and direct and indirect healthcare costs).2

Current Treatment Options

The overall goal of CSU treatment is to “treat the disease until it is gone,”1 which is crucial for patient quality of life.5 However, CSU can be difficult to treat, which is frustrating for both patients and physicians.6 The therapeutic approach can involve identifying and eliminating eliciting factors, and pharmacological treatment directed at mast cells and mast cell mediators.1

The recommended first- and second-line therapy for CSU is a standard-dosed and updosed second-generation, nonsedating H1-antihistamine, respectively.1 However, this fails to control symptoms in >50% of CSU patients.2,7 Although updosing of H1-antihistamines improves treatment responses,1 many patients remain symptomatic.8 After failure of H1-antihistamines, the third-line treatment option is to target IgE with omalizumab;1,9 however, complete symptom control is not achieved in >50% of CSU patients even after 12 weeks of treatment with omalizumab 300 mg.10

Aetiology

CSU symptoms occur because of mast cell activation and the release of proinflammatory mediators (e.g., histamine).11 There are two types of autoimmunity that drive the pathogenesis of CSU.11 In patients with Type I autoimmune CSU (autoallergy), autoimmunity is IgE-driven, with IgE autoantibodies that bind to mast cells. When the autoallergen is bound by this IgE, there is cross-linking of IgE receptors.11 Type IIb autoimmunity is characterised by IgG or IgM autoantibodies that are directed to the mast cell itself, with either the IgE receptor on mast cells or the IgE bound to them.11 Both types result in downstream mast cell activation or degranulation and hives and/or angioedema.

IgE binds to two main receptors: high-affinity FcεRI receptors and low-affinity CD23 (FcεRII) receptors.12 The resultant IgE cross-linking leads to cell activation and degranulation.12,13 The released proinflammatory and vasoactive mediators result in the clinical manifestations of CSU. This can also be triggered directly by autoantibodies attaching to the FcεRI receptors. Either way, the IgE receptor is key to mast cell activation in CSU.13,14 Therefore, an anti-IgE drug that prevents mast cell activation reduces the symptoms of CSU.

Anti-IgE Antibodies

As the IgE/Fcε RI axis plays a central role in allergen and autoantigen-driven inflammation in CSU, the goal of the anti-IgE approach is to bind and neutralise free IgE in a patient’s serum.15 The anti-IgE antibodies thus block the binding of IgE to the high-affinity receptors on mast cells and basophils, resulting in reduced hypersensitivity reactions and fewer CSU symptoms (hives, itching, and angioedema).

Two anti-IgE antibodies have shown efficacy in CSU: omalizumab, which is currently licensed for the treatment of CSU; and ligelizumab, which is a next-generation, high-affinity, humanised monoclonal anti-IgE antibody that is currently in development for the treatment of patients with CSU who are inadequately controlled by an H1-antihistamine.16 These two antibodies have distinct molecular properties and modes of action, as discussed in this article.

In a Phase I double-blind study, atopic subjects were randomised to receive 2–4 doses of subcutaneous ligelizumab 0.2, 0.6, 2.0, or 4.0 mg/kg or placebo every 2 weeks, and the results were compared with an open-label omalizumab arm.17 At a dose of 4.0 mg/kg, ligelizumab reduced the amount of free IgE to a much greater extent than omalizumab, and the reduction persisted for considerably longer.17 There was a concomitant rapid increase in total IgE with ligelizumab because of the formation of stable complexes between IgE and ligelizumab, and this persisted for longer than with omalizumab.17

A recent binding study has shown that ligelizumab has an approximately 90-fold higher affinity for IgE than omalizumab.15 This is partly because of the higher association constant of ligelizumab’s antigen-binding fragment compared to omalizumab’s antigen-binding fragment (9.2×106 versus 1.5×106 M–1s–1, respectively), but mainly because of the much lower dissociation constant (3.2×10–4 versus 4.6×10–3 s–1, respectively), resulting in a considerably lower equilibrium dissociation constant (35 versus 3090 pM, respectively).15 This likely explains the more stable complex seen in the previous study.

By examining the crystal structures of complexes between IgE and either ligelizumab or omalizumab, it has been shown that ligelizumab binds to a different IgE epitope than omalizumab.15 Although both antibodies bind in the same IgG domain (Cε3), ligelizumab binds more proximally to the Cε2 domain and has an important overlap with the binding site for the high-affinity FcεRI receptor.15 In contrast, omalizumab binds closer to the Cε4 domain, i.e., further from the FcεRI site, instead directly competing with the low-affinity CD23 receptor.15 Of note, ligelizumab can bind to IgE that is already bound to CD23, but not IgE that is bound to FcεRI.15 Lastly, ligelizumab preferentially binds to an open conformation of IgE, in a similar way to when it binds to the high-affinity receptor.15 These data predict better inhibition of an interaction between IgE and FcεRI with ligelizumab, and better inhibition of an interaction between IgE and CD23 with omalizumab, and this has been confirmed in functional assays.15 Because of its stronger inhibition of IgE binding to FcεRI, ligelizumab is predicted to be more effective than omalizumab in CSU.

Ligelizumab also suppresses the production of IgE by B cells (in peripheral blood mononuclear cells stimulated with anti-CD40 and IL-4) to a greater extent than omalizumab,15 which could further explain the prolonged suppression of free IgE in patients receiving ligelizumab.

Overall, omalizumab is more efficient at suppressing CD23-related pathways, which are heavily involved in allergic asthma, while ligelizumab is more efficient in FcεRI-mediated pathways, which are heavily involved in CSU and food allergies.

Phase IIb Ligelizumab Study

Study Design and Patient Disposition

In a key Phase IIb, randomised, double-blind, dose-finding study of ligelizumab for CSU,18 following a 2-week screening period, 382 adult patients with moderate-to-severe CSU (UAS7≥16 on a scale of 0–42, with higher scores indicating more severe disease) that was inadequately controlled with an H1-antihistamine were randomised to recieve:16

- Ligelizumab 24 mg q4w (n=43)

- Ligelizumab 72 mg q4w (n=84)

- Ligelizumab 240 mg q4w (n=85)

- Omalizumab 300 mg q4w (n=85)

- Placebo q4w (n=43)

- One dose of ligelizumab 120 mg followed by placebo q4w (n=42) (for pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic characterisation).

The treatment phase lasted until Week 20, with treatments given subcutaneously at Weeks 0, 4, 8, 12, and 16, after which patients were followed up to Week 32–44 without treatment. From Week 32, patients could enrol in a 1-year extension study19 on ligelizumab 240 mg q4w if their UAS7 was ≥12. They were then followed up for a further year without treatment to assess the durability of the treatment effect. Of the 226 patients who entered the extension study, 201 completed this open-label phase.

Core Study Results

At Week 12, HSS7=0 (primary outcome measure) had been achieved by 30.2%, 51.2%, and 42.4% of patients on ligelizumab 24, 72, and 240 mg, respectively, compared with 25.9% of those on omalizumab and no patients in the placebo arm.16 Similarly, UAS7=0 at Week 12 was achieved by 30.2%, 44.0%, and 40.0% of patients on ligelizumab 24, 72, and 240 mg, respectively, compared with 25.9% of patients on omalizumab and no patients in the placebo arm.16 Mean changes in UAS7 scores from baseline to Week 12 were -16.5 with ligelizumab 24 mg, and -22.0 and -21.8 with ligelizumab 72 and 240 mg, respectively, compared with -17.9 with omalizumab and -13.4 with placebo.20

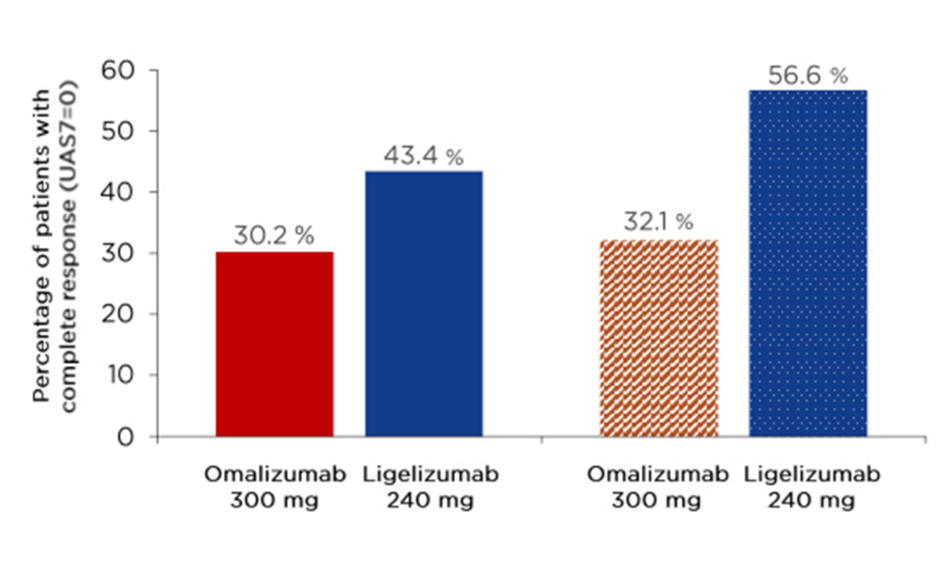

In an exploratory analysis, which included the ligelizumab 72 and 240 mg groups and the omalizumab group, efficacy results were examined according to baseline CSU activity. CSU disease activity was categorised into five groups based on UAS7 scores: 0 (urticaria free), 1–6 (low activity), 7–15 (mild), 16–27 (moderate), and 28–42 (severe). At baseline, most patients had severe CSU activity (58.8–75.0% in the three reported treatment groups) or moderate CSU activity (23.8–37.6%). Among those with moderate CSU activity at baseline, a complete response (UAS7=0) was achieved by Week 4 in 35.0% and 25.9% of patients on ligelizumab 72 and 240 mg, respectively, compared with 12.5% of patients on omalizumab. A further 35.0% (ligelizumab 72 mg), 22.2% (ligelizumab 240 mg), and 21.9% (omalizumab) of patients achieved UAS7 1–6. Achievement of UAS7=0 increased to 60.0% (ligelizumab 72 mg), 40.7% (ligelizumab 240 mg), and 34.4% (omalizumab) of patients by Week 12; a further 20.0% (ligelizumab 72 mg), 14.8% (ligelizumab 240 mg), and 25.0% (omalizumab) of patients achieved UAS7 1–6. Up to 90% of patients decreased by ≥1 activity level, and up to 70% and 80% of ligelizumab-treatment patients at Week 4 and Week 12, respectively, were considered well controlled. Among those with severe CSU activity, most patients achieved improvements in UAS7 scores, with 38.1% (ligelizumab 72 mg), 41.1% (ligelizumab 240 mg), and 20.0% (omalizumab) achieving UAS7=0 by Week 12 (Figure 1). Up to 70% of patients improved by ≥1 activity band.

Figure 1: Among patients with severe chronic spontaneous urticaria, more ligelizumab- than omalizumab-treated patients achieved a complete response.

*The percentages do not add up to 100% as some subjects discontinued the study early or data from their visit were missing.

q4w: every 4 weeks; UAS7: weekly Urticaria Activity Score.

Quality of Life Outcomes

Quality of life outcomes were studied amongst a subgroup of CSU patients with angioedema at baseline (ligelizumab 72 mg [n=43], ligelizumab 240 mg [n=46], omalizumab 300 mg [n=48], or placebo [n=28]). Patients in the two ligelizumab groups achieved dramatic and sustained improvements in UAS7 as early as Week 4 (i.e., after just one dose): baseline → Week 4 → Week 12 → Week 20 mean UAS7 were 33 → 12 → 10 → 9 with ligelizumab 72 mg and 30 → 13 → 9 → 7, respectively, with ligelizumab 240 mg. Scores also improved in the omalizumab group, but to a somewhat lesser extent (30 → 16 → 13 → 11, respectively). Patients in the placebo group also experienced some improvement (32 → 26 → 17 → 16, respectively), caused by spontaneous resolution of symptoms. Improvements in mean AAS7 followed a generally similar pattern, with those in the ligelizumab 72 mg (42 → 8 → 6 → 6, respectively) and ligelizumab 240 mg (33 → 12 → 7 → 5, respectively) groups achieving large, rapid reductions in AAS7, with similar results in the omalizumab group (31 → 12 → 7 → 4, respectively), and a smaller spontaneous improvement in the placebo group (40 → 22 → 14 → 14, respectively). Mean DLQI scores at baseline were approximately 15 in each of the four groups. At Week 4, these had decreased to 5 (ligelizumab 72 mg), 6 (ligelizumab 240 mg), 7 (omalizumab), and 11 (placebo). At Week 12, mean DLQI scores were 4–6 in all four groups, and at Week 20, the mean DLQI score in the ligelizumab 240 mg group was 3, compared to 6–7 in the other three groups. Therefore, the decreases in the UAS7 and AAS7 that were observed over time in each treatment arm were accompanied by improvements in DLQI.

Pearson correlation coefficients (r-values) for UAS7 and AAS7 with DLQI were calculated for each treatment group, using pooled data from baseline to Week 20. Significant correlations between UAS7 and DLQI were observed in each treatment arm, with r-values of 0.85 (ligelizumab 72 mg), 0.81 (ligelizumab 240 mg), 0.78 (omalizumab), and 0.69 (placebo) (all p<0.001), indicating stronger correlations in the ligelizumab groups. Similarly, r-values for the correlations between AAS7 and DLQI were 0.66 (ligelizumab 72 mg), 0.66 (ligelizumab 240 mg), 0.59 (omalizumab), and 0.52 (placebo) (all p<0.001). These results indicate that a reduction in symptoms (itch, hives, and angioedema) based on effective treatment correlates with an improvement in quality of life, and therefore wellbeing.

Extension Study Results

Four weeks after the first dose of ligelizumab 240 mg in the 1-year extension study, 35.4% of patients had achieved UAS7=0,21 which increased steadily to 53.1% after 1 year of treatment.22 Similarly, 54.4% achieved UAS7≤6 (i.e., mild disease) after one dose, increasing to 61.1% after 1 year.22

At the start of the 1-year extension study, 33.2% of patients had angioedema, which fell to 10.8% by Week 4 and 7.0% by Week 52.21 Mean changes from baseline in AAS7 (on a scale of 0–105, with higher scores indicating higher severity) increased from -23.2±23.7 at Week 4 (equating to a 71.9% reduction from baseline) and from -27.4±24.6 at Week 52 (equating to an 86.3% reduction from baseline).22

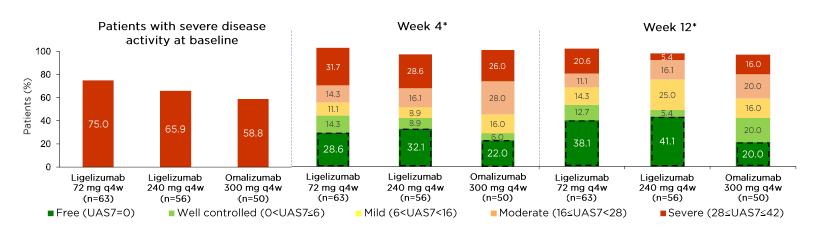

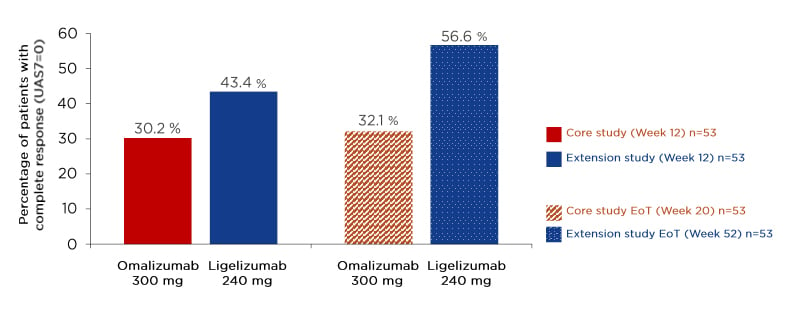

There were some interesting results among the 53 patients who received omalizumab 300 mg in the core study and then went on to receive ligelizumab 240 mg in the extension study. After 12 weeks of omalizumab 300 mg treatment in the core study, 30.2% of these 53 patients had achieved UAS7=0, and this increased slightly to 32.1% after 20 weeks. However, after 12 weeks of ligelizumab 240 mg in the extension study, 43.4% of these same patients achieved UAS7=0, increasing to 56.6% after 52 weeks (Figure 2). Therefore, while the core study demonstrated greater improvements with ligelizumab than omalizumab in a parallel-group design, the extension study results showed that patients who received omalizumab followed by ligelizumab were more likely to achieve a complete response with ligelizumab.

Figure 2: Patients who received omalizumab 300 mg during the core study followed by ligelizumab 240 mg in the extension study were more likely to achieve a complete response on ligelizumab.

EoT: end of treatment; q4w: every 4 weeks; UAS7: weekly Urticaria Activity Score.

Post-Treatment Follow-Up Results

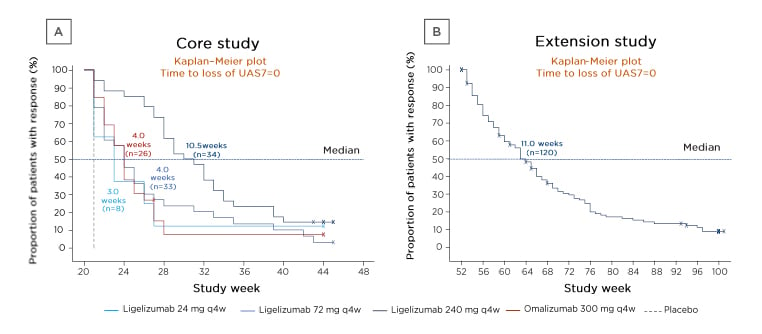

There were two treatment-free follow-up periods, which occurred between the 20-week core study and the 1-year extension study (n=349), and during the 1-year treatment-free follow-up after the 1-year extension study (n=201). The Kaplan–Meier median method was used to calculate the median times to: a) loss of complete control (UAS7=0) for each treatment group after the core study, and after the 1-year treatment period of the extension study; b) loss of well-controlled urticaria activity (UAS7≤6) after the core and extension studies; and c) relapse (UAS7≥16) during the follow-up period after the 1-year extension study.

After the end of the double-blind treatment period in the core study (Week 20), the median time to loss of completely controlled CSU (UAS7=0) was longest amongst the 34 patients who had achieved complete control on ligelizumab 240 mg (10.5 weeks) (Figure 3A). So, after stopping treatment at the end of the 20-week core study, it took 10.5 weeks for 50% of the patients on ligelizumab 240 mg who achieved UAS7=0 to lose this control. Median time to loss of complete control was similar amongst patients who had achieved complete control on ligelizumab 72 mg (4.0 weeks), ligelizumab 24 mg (3.0 weeks), and omalizumab (4.0 weeks) (Figure 3A).23

During the treatment-free follow-up period after the 1-year extension study, in which all patients received ligelizumab 240 mg, the median time to loss of UAS7=0 was 11.0 weeks amongst the 120 patients who had achieved this (Figure 3B).23

Figure 3: Kaplan–Meier plots of the times to loss of weekly Urticaria Activity Score (UAS7=0) during the treatment-free follow-up periods after the two treatment periods.

A) The 20-week core study and B) the 1-year extension study.23

X indicates censored patients who left the study without an observed loss of response.

q4w: every 4 weeks; UAS7=0: weekly Urticaria Activity Score.

Similarly, the median time to loss of well-controlled CSU (UAS7≤6) was longest amongst the 38 patients who had achieved this control on ligelizumab 240 mg (14.0 weeks), followed by 7.0 weeks amongst those on ligelizumab 72 mg (n=51) or omalizumab (n=36), and 4.0 weeks for ligelizumab 24 mg (n=17).23 After the end of the 1-year extension study (ligelizumab 240 mg), the median time to loss of UAS7≤6 was even longer (21.0 weeks) (n=138).23

The median time to relapse (UAS7≥16) amongst patients whose symptoms were previously well controlled (UAS7≤6) at the end of ligelizumab 240 mg treatment during the 1-year extension study was 38.0 weeks (n=138).23

Safety

All tested ligelizumab doses were well tolerated, with a safety profile that was comparable to those of omalizumab and placebo.24 In the core study, in all treatment groups combined, adverse events were predominantly mild (39.8%) or moderate (30.6%).24 Severe adverse events were less frequent in the ligelizumab groups (3.5–9.3%) than with placebo (16.3%).24 Serious adverse events were reported by 7.0%, 2.4%, and 2.4% of patients on ligelizumab 24, 72, and 240 mg, respectively; 3.5% of those on omalizumab; and 9.3% of those on placebo in the core study, as well as 5.8% of patients on ligelizumab 240 mg in the extension study.25 Adverse events only led to treatment discontinuation in 0.0%, 1.2%, and 1.2% of patients on ligelizumab 24, 72, and 240 mg, respectively; 2.4% of those on omalizumab; and 4.7% of placebo patients in the core study, as well as 3.5% of patients on ligelizumab 240 mg in the extension study.25

Conclusion

The efficacy and safety of omalizumab are well established,26 and it is the third-line treatment option in international guidelines.1 However, ligelizumab is more effective at inhibiting the IgE/FcεRI pathway than omalizumab, has a higher affinity to IgE, and results in deeper suppression of IgE.15 Phase IIb data indicate that patients can achieve greater symptom improvements with ligelizumab versus omalizumab, when compared in a parallel-group design and when patients who received omalizumab subsequently received ligelizumab. Ongoing Phase III ligelizumab clinical trials include PEARL 127 and PEARL 2,28 in which patients inadequately controlled with H1-antihistamines are being randomised to ligelizumab, omalizumab, or placebo; and an open-label extension study.29 These will evaluate the efficacy and safety of ligelizumab treatment for up to 1 year in patients with CSU that is inadequately controlled with H1-antihistamines at approved doses. Although ligelizumab is not yet approved for use, it is hoped that these new ligelizumab data may impact upon the CSU guidance algorithms in the future.