Abstract

Drug allergies, also termed adverse drug reactions (ADRs), are a problem for individuals of all ages, from paediatric to geriatric, and in all medical settings. They may be a predictable reaction to a specific drug (termed Type A) or particular to the individual (termed Type B). Health professionals, especially those caring for patients at the point of entry into the medical system, have a very important role in determining if and when a patient is having an ADR. The purpose of this article is to review the pathophysiology of ADRs, describe the signs and symptoms of different classifications of ADRs, and present the medical and wound treatment for patients with systemic and cutaneous reactions to drug allergies.

INTRODUCTION

An adverse drug reaction (ADR) is defined by the World Health Organization (WHO) as “a response to a medicine which is noxious and unintended, and which occurs at doses normally used in man.” ADRs account for 3–6% of all hospital admissions and occur in 10–15% of hospitalised patients.1 Drug allergies are one type of ADR and are defined by the Joint Task Force on Practice Parameters (representing the American Academy of Allergy, Asthma and Immunology [AAAAI]; the American College of Allergy, Asthma and Immunology [ACAAI]; and the Joint Council of Allergy, Asthma and Immunology [JCAAI]) as “an immunologically mediated response to a pharmaceutical and/or formulation (excipient) agent in a sensitized person.”2 This definition implies that the reaction can have both immunoglobulin (Ig)E-mediated and non-IgE-mediated mechanisms.

Incidence and prevalence of ADRs is uncertain because of the variability in studies. For example, the setting, patient population, age, and case verification all differ in the following reported studies. The Boston Collaborative Drug Surveillance Program, established in 1966, is a pharmacoepidemiologic research programme that continues to conduct studies on pharmaceutical drug reactions in a variety of settings and patient populations. An extensive list of their publications can be accessed at http://www.bu.edu/bcdsppublications.3 Early studies of 15,438 in-patients reported an overall 2.2% reaction rate, with the highest rates causes by amoxicillin, trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, and ampicillin (51.4/1,000, 33.8/1,000, and 33.2/1,000, respectively).4 A 6-month French study of cutaneous allergic reactions from systemic drugs occurring in a hospital setting found a rate of 3.6 per 1,000 patients had reactions.5 A similar 10-month study in Mexico found a prevalence of 7 per 1,000 patients.6 Two studies have reported both systemic and cutaneous reactions that were confirmed by allergists in an in-patient setting. One study in Singapore reported 366 cases from 90,910 admissions, and one in Korea reported 2,682 cases among 55,432 admissions.1 Numerous other studies and meta-analyses have been reported in the literature on drug allergies for patients in various settings, on both adults and children, and on various individual medications.1,7-9

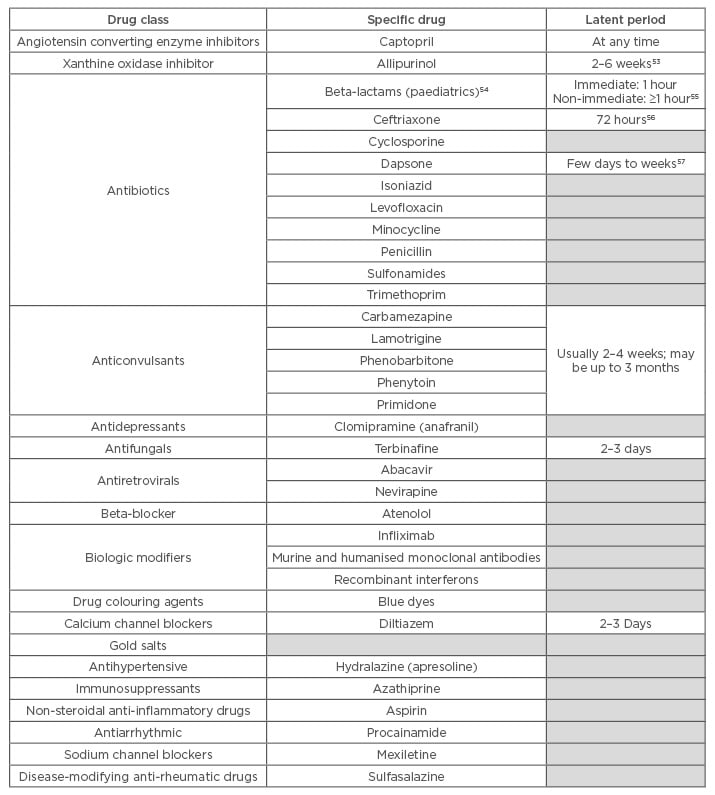

For example, the incidence of drug hypersensitivity syndrome (DHS) with anticonvulsants has been estimated at 1 in 10,000 exposures.10 Table 1 shows a list of the most common drugs that have been found to induce drug allergies.2,11-13

Table 1: Most common drugs that induce drug hypersensitivity reactions.

Multiple DHS (MDH) was first described by Sullivan et al.14 in 1989 and is defined as a drug allergy to two or more chemically different drugs, mainly antibiotics. Chiriac and Demoly15 further described the multiple drug intolerance syndrome in which patients reported “various adverse drug reactions to three or more chemically, pharmacologically, and immunogenically unrelated drugs, taken independently, and who display certain negative allergological tests.” Two subtypes of MDH syndrome were proposed by Gex-Collet et al.,16 one which develops against different drugs given simultaneously and a second which develops when sensitisations appear sequentially, sometimes years apart. Using both a skin patch test and the lymphocyte transformation test, they found sensitivity to antibiotics as well as anti-epileptics, hypnotics, antidepressants, local anaesthetics, and corticosteroids.16 Studies have shown that 1–5% of all patients with drug allergies have MDH syndrome.17

Risk factors that have been associated with ADRs can be host-related or drug-related. Host-related factors include female sex,18 concomitant diseases (such as HIV, reactivation of herpes virus, and renal or liver disease), ethnicity, polypharmacy, alcoholism, and genetic predisposition.1,19 Certain classes of drugs tend to be associated with a higher incidence of drug allergies, based upon their ability to act as a hapten, prohapten, or covalent binder to immune receptors.1 The method of drug administration can also affect the frequency of ADRs; topical, intramuscular, and intravenous (IV) methods are more likely to cause hypersensitivity reactions than oral medications.19

PATHOPHYSIOLOGY OF DRUG ALLERGIES

The pathophysiology of drug allergies is not fully understood; however, the cell-mediated immune reaction and the activation of T cells is proposed to occur through three different mechanisms:

- The hapten/prohapten hypothesis,

- The pharmacologic interaction with immune receptor (p-i) model

- The altered peptide repertoire hypothesis8

According to the hapten/prohapten hypothesis, the causative drug acts as either a hapten (a small chemical molecule that forms covalent attachment to a protein), prohapten (a chemical that can be converted to a hapten), an antigen, a co-stimulatory agent, an immunogen, or a sensitogen (a chemical that can elicit hypersensitivity in humans).20,21

The drug acting as a hapten binds covalently to serum or cell-bound proteins, including peptides embedded in major histocompatibility complex (MHC) molecules.22 The chemical reaction activates the T cell, thereby initiating an immune response that can cause systemic or cutaneous reactions, and immediate or delayed side effects. Although drug–hapten complexes have been detected in vivo for a number of drugs, the exact mechanism of MHC molecule binding and T cell activation has not yet been defined.20

The p-i model was proposed by Pichler23 and is based on the direct binding of the parent drug to the T cell receptor or the human leukocyte antigen (HLA) which results in T cell activation and a subsequent immune response.

The altered peptide repertoire hypothesis states that low-molecular-weight drugs bind non-covalently to parts of the HLA molecules within the antigen-binding cleft, thereby altering the shape of the cleft and the repertoire of peptides that are presented. If the subject is not tolerant to the new peptides presented, a T cell response is initiated with an immune response via interaction with a MHC.8 No sensitisation is required in this case because there is direct stimulation of memory and effector T cells.2

A study by Bellón et al.24 supported the T cell-mediated hypothesis by identifying 85 genes that were differentially expressed during the acute phase of drug-induced hypersensitivity syndrome (DIHS). Most of the genes upregulated in the acute phase were encoding proteins involved in the cell cycle, apoptosis, and cell growth functions; nine were involved in immune response and inflammation. They also found that histone messenger RNA levels were statistically significantly increased in severe and moderate reactions. Genes that were strongly upregulated in syndromes that include both cutaneous and mucosal involvement were those involved in inflammation, now termed alarmins or endogenous damage-associated molecular patterns.24

Associations have been discovered between HLA alleles and many of the serious cutaneous adverse reaction syndromes. This includes abacavir hypersensitivity reaction; allopurinol drug reaction, eosinophilia, and systemic symptoms (DRESS)/DIHS; and Stevens–Johnson syndrome (SJS)/toxic epidermal necrolysis (TEN) associated with aromatic amine anticonvulsants.9 Two studies (PREDICT-1 and SHAPE) have shown 100% negative predictive value of HLA-B*5701 for abacavir hypersensitivity across both Caucasian and African-American populations. Other specific correlations that have been found include nevirapine reactions with HLA-B*3505/01 and HLA-DRB1*0101; allopurinol with HLA-B*5801, carbamazepine with HLA-B*1502 and HLA-B*5701; abacavir, flucloxacillin, and neviraine with HLA-B*3505/01.9

A study by Picard et al.25 also detected Epstein-Barr virus (EBV), human herpes virus 6, or human herpes virus 7, reactivation in 76% of the patients with DRESS in response to carbamazepine, allopurinol, or sulfamethoxazole. Circulating CD8+ T lymphocytes were activated in all of these patients and nearly half of the expanded blood CD8+ T lymphocytes sharing the same T cell receptor repertoire detected in the blood, skin, liver, and lungs, recognised one of several EBV epitopes. They concluded that “cutaneous and visceral symptoms of DRESS are mediated by activated CD8+ T lymphocytes, which are largely directed against herpes viruses such as EBV.”25

The reaction to anticonvulsant medications, termed anticonvulsant hypersensitivity syndrome (AHS), has been linked to the presence of arene oxides. Arene oxides are intermediate metabolites produced by the metabolisation of the drugs by cytochrome P-450 and usually detoxified by epoxide hydroxylase; however, there is evidence that individuals who develop AHS are unable to detoxify arene oxides.26,27

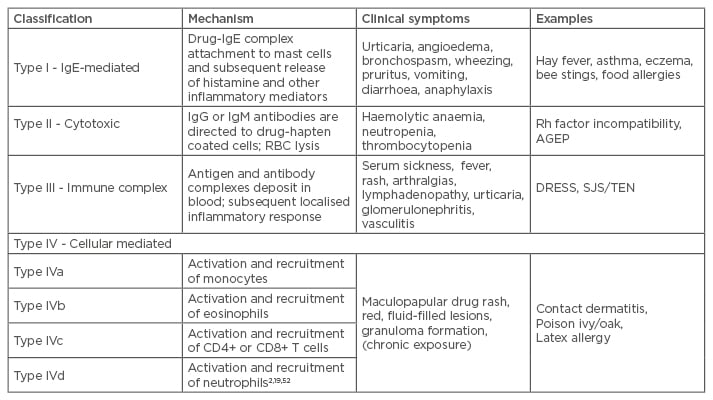

ADRs have been classified as Type A: those that are predictable and dose dependent reactions, including overdose, side effects, and drug interactions (e.g. a gastrointestinal bleed following treatment with non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs [NSAIDs]); and Type B, those that are unpredictable, more likely to be dose independent, and may include immunologically mediated drug hypersensitivity or non-immune mediated reactions, thus being considered allergic reactions.1,8 A more extensive classification, the Gell and Coombs system, describes the predominant immune mechanisms that lead to the clinical symptoms of hypersensitivity and is presented in Table 2.19 The table also reflects recent modifications based upon the cells recruited and activated in Type IV reactions.

Table 2: The Gell and Coombs classification system for drug hypersensitivity.

RBC: red blood cell; DRESS: drug rash with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms; SJS/TEN: Stevens-

Johnson syndrome/toxic epidermal necrolysis; Ig: immunoglobulin; Rh: rhesus; AGEP: acute generalised exanthematous pustulosis.

Clinical Presentation

Signs and symptoms of allergic reactions usually occur 1–3 weeks after the first exposure or ingestion of the causative medication and can either be local (caused by contact dermatitis), systemic, or cutaneous. The local erythema, rash, and pruritis associated with contact dermatitis (Type IV) will follow the pattern of contact with the offending substance, e.g. an allergic reaction to a silver dressing or elastic wrap (Figure 1). This type of reaction is more easily identified than an ingested drug, and is effectively treated with discontinuation of the causative solution or material and the application of a topical anti-inflammatory cream.

Figure 1: Contact dermatitis. The distinct line of erythema at the distal leg is indicative of an allergic reaction to the elastic compression used to manage chronic oedema.

Typically, the erythematous, maculopapular rash that appears within 1–3 weeks after drug exposure will occur first on the trunk and then spread to the extremities. Urticaria is typically a manifestation of a Type I allergic reaction; however, it may also appear with Type III or pseudo-allergic reactions.19

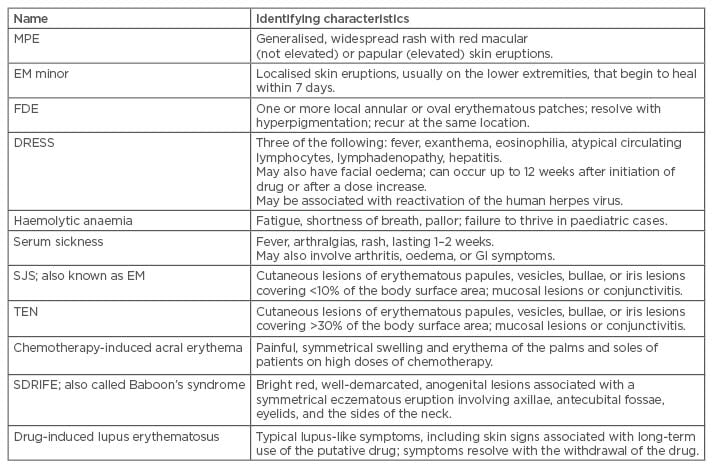

Systemic symptoms vary from mild to severe, and can involve the liver, kidneys, lungs, bone marrow, and other autoimmune phenomena.20,22 The most common syndromes involving both systemic and cutaneous events are listed in Table 3. Warning signs of a severe life-threatening reaction due to cardiovascular collapse include urticaria, laryngeal or upper airway oedema, wheezing, and hypotension.19 Fever, mucous membrane lesions, lymphadenopathy, joint tenderness and swelling, and abnormal respiratory examination are also signs of serious systemic reactions.

Table 3: Drug hypersensitivity reactions based on severity of symptoms.

MPE: maculopapular exanthemas; SJS: Stevens-Johnson syndrome; EM: erythema multiforme; FDE: fixed drug eruption; DRESS: drug rash with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms; TEN: toxic epidermal necrolysis; SDRIFE: symmetrical drug related intertriginous and flexural exanthema; GI: gastrointestinal.

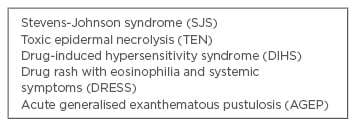

Cutaneous reactions can also vary from mild itching to severe syndromes such as SJS, TEN, DRESS, or acute generalised exanthematous pustulosis (AGEP). Serious cutaneous adverse reactions are associated with a high rate of morbidity and mortality (Table 4).1

Table 4: Severe cutaneous adverse reactions.

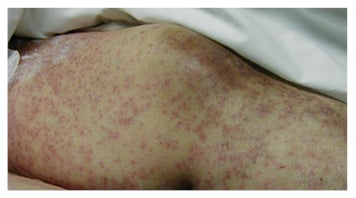

SJS and TEN begin with a fever, sore throat, and stinging eyes for 1–3 days, followed by mucosal lesions involving conjunctive, oral and genital mucosa, trachea, bronchi, and gastrointestinal tract. Cutaneous lesions develop next with erythematous macules, progressing to flaccid blisters that tear easily (Figure 2).28 Because of the target appearance and two zones of colour, these initial lesions are referred to as targetoid lesions;29 they involve almost all of the body, including the head, anterior and posterior trunk, upper and lower extremities, and may also progress to the lower back and gluteal region. Signs of impending severe cutaneous reactions are skin pain, epidermolysis, and a positive Nikolsky sign (slight rubbing of the skin causing epidermal/ dermal separation).30

Figure 2A: Sloughing blisters on the skin of a patient with toxic epidermal necrolysis.

Figure 2B: Vasculitic cutaneous reaction on the lower extremities in response to ingestion of an antibiotic.

AGEP is characterised by numerous small, primarily non-follicular, sterile pustules that present within large areas of oedematous erythema; however, unlike SJS they do not occur in the mouth and vagina. AGEP is also accompanied by fever, neutrophilia, and sometimes by facial oedema, hepatitis, and eosinophilia.31

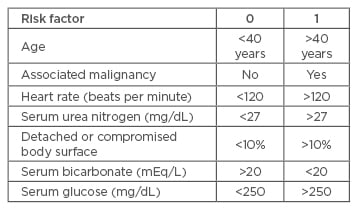

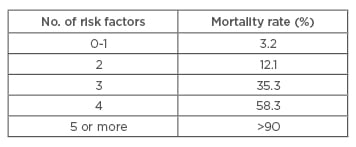

The SCORTEN scale (SCORe of Toxic Epidermal Necrosis) is a severity-of-illness scale that can be used to determine the mortality risk of an individual patient.32 Although it was initially developed for patients with SJS and TEN, it has been validated and used for patients with burns and other exfoliative disorders. Calculations should be performed within the first 24 hours after admission and on Day 3.32 Table 5 and Table 6 list the risk factors and mortality scores, showing that more risk factors result in a higher score on the SCORTEN scale, thereby indicating a higher mortality rate.

Table 5: SCORTEN (SCORe of Toxic Epidermal Necrosis) Scale risk factors for determining mortality rates of patients with toxic epidermal necrolysis or Stevens-Johnson syndrome.

Table 6: Interpretation of the SCORTEN (SCORe of Toxic Epidermal Necrosis) Scale.

DIAGNOSIS

Any patient who exhibits the signs of drug allergy should first have an extensive review of their subjective medical history and be evaluated for a differential diagnosis which would include close scrutiny of all medications, both prescribed and over-the-counter. Special attention is advised to the temporal relationship between initiating a drug and the onset of clinical symptoms. Any report of previous allergies may be an indicator of risk for a newly-observed allergic reaction. For example, this author found that patients who reported allergies to latex may be more likely to develop allergic reactions to dressings with topical antimicrobials. The medical history is accompanied by an intensive integumentary examination for any skin changes; the type of skin reaction is critical for providing clues to the immune-mediated mechanism of the drug reaction.19

Patch or skin tests to detect antigen-specific IgE are useful in most forms of DIHS, specifically for Types I and IV, but not for SJS/TEN and vasculitis. Type II cytotoxic reactions can be detected by a complete red blood count, as haemolytic anaemia, thrombocytopenia, or neutropenia will be evident.19

Diagnostic laboratory values can play a role in prognosis of the disease, especially TEN and SJS. Neutropenia and lymphopenia can occur and may be a negative prognostic factor.33 The use of granulocyte-colony-stimulating factor in the treatment of TEN has been shown to reverse the neutropenia with a corresponding increase in re-epithelialisation.30 Hyperferritinemia as a result of acute liver failure can be a useful marker for the severity of DIHS.34 Fujita et al.35 developed a rapid immunochromatographic test for detection of granulysin, a cytotoxic lipid-binding protein that causes apoptosis and is present in the blister fluid of patients with SJS/TEN. The granulysin was found to be elevated before skin and mucosal detachment occurred, suggesting that it may be a useful marker for detection of SJS/TEN in the early stages.

A retrospective study by Watanabe et al.36 suggested distinct differences between SJS/TEN and erythema multiforme major (EMM) which can be helpful in making a definitive diagnosis. SJS/TEN patients were more likely to have mucous membrane involvement, higher C-reactive protein levels, and hepatic dysfunction. EMM patients had stronger mononuclear cell infiltration and required lower doses of systemic corticosteroids.

Sun et al.37 studied the potential of the drug-induced lymphocyte test in patients with tuberculosis, and found that it has high specificity and limited sensitivity in the diagnosis of anti-tuberculosis drug-induced ADRs, suggesting that it may have predictive validity for ADRs, especially when the result is positive. The basophil activation test (BAT) has been used to detect an immediate reaction to pristinamycin38 as well as neuromuscular blocking agents, antibiotics, NSAIDs, and iodinated radiocontrast media.39 Both authors concluded that more large-scale multicentre studies are needed to validate the use of BAT as a diagnostic test in drug allergies.

The drug provocation test (DPT) is used to detect immediate hypersensitivity reactions, and can be beneficial in predicting immediate reactions in children who have a history of non-immediate reactions to amoxicillin.40 Alvarez-Cuesta et al.41 studied the use of DPT with patients who were on anti-neoplastic or biological agents. They found that the DPT was helpful in excluding hypersensitivity in 36% of referred patients and avoided unnecessary desensitisation in non-hypersensitive patients in 30–56% of the subjects tested, depending upon the culprit drug.

TREATMENT OF DRUG ALLERGIES

The first and foremost medical strategy is identification and cessation of the causative agent, usually the last one the patient initiated 1–3 weeks prior to onset of symptoms. An exception is DRESS which can occur after a longer latent period (1–8 weeks), in these cases it is recommended to consider medications started within the 6 months prior to onset of symptoms.42 Thereafter treatment is predicated upon the severity of the symptoms, both cutaneous and systemic. Reactions that cause drug fever, a non-pruritic rash, or mild organ system reactions may require no treatment other than discontinuance of the medication.22 Corticosteroids are used for both treatment of symptoms and prevention of progression. Recommended systemic corticosteroids dosing begins at 0.5–1 mg/kg/day and is tapered over 6–8 weeks; for SJS, 1 mg/kg/day of prednisolone or 1–2 mg/kg/day of methylprednisolone.43 Topical steroid ointments and oral histamines are also beneficial for dermatologic symptoms, and may be sufficient in milder cases. Steroid therapy for TEN is reported as both controversial and no longer recommended; if used, it should be within the first 48 hours of treatment due to the increased risk of septic complications with an anti-inflammatory agent. Strict control of blood glucose levels is needed for patients with history of diabetes or on corticosteroids.44

For patients with extensive skin involvement, supportive care in an acute burn or intensive care unit is recommended for prevention of infection, life support measures, and pain management.45 Mechanical ventilation, fluid resuscitation with IV fluids such as Ringer’s solution for electrolyte balance, anti-coagulation with heparin to prevent thromboembolism, and supplemental nutrition via a nasogastric tube may be needed in severe cases.12,46 Antibiotic therapy is not given as a prophylactic measure but dependent upon clinical symptoms, including positive skin cultures, sudden drop in temperature, or deterioration of the patient’s medical condition.2,45 In order to prevent caloric loss and an increase in metabolic rate, a room temperature of 30–32°C is also recommended.46

Clinical studies on the use of IV lg for patients with SJS and TEN have shown mixed results. Successful treatment appears to be dose dependent (1 g/kg/day for 3 days with a total of 3 g/kg over 3 consecutive days) with early treatment recommended.47 Other medications which have been studied and found beneficial include IV infleximab, cyclosporin, and IV N-acetylcysteine.28 Aciclovir has been suggested for lesions that occur in the oral cavity of patients with TEN.48

Desensitisation is a possible treatment strategy, especially for patients with IgE-mediated drug allergies (e.g. certain antibiotics, platinum salts, monoclonal antibodies), as well as those on taxanes or chemotherapy. Desensitisation involves administering a low dose of the drug and gradually increasing the dose every 15–30 minutes until the therapeutic dose is reached. The dose is then administered at regular intervals for the duration of treatment which also maintains the desensitised state.8,49 All patients with known drug allergies require education regarding future episodes, cross-reacting drugs to avoid, and the benefit of wearing a medical-alert device.

WOUND MANAGEMENT

For severe cases involving loss of epidermis, wound management goals are to prevent fluid loss, prevent infection, and facilitate re-epithelialisation. Although patients with SJS/TEN are best treated in an acute burn centre, there are some definite differences in their clinical presentation that affects treatment. For example, SJS/TEN epidermal involvement may continue to spread after admission; subcutaneous necrosis is deeper in burns, thereby creating subcutaneous oedema that is not observed in SJS/TEN; fluid requirements for SJS/TEN are usually two-thirds to three-quarters those of burn patients with the same area involvement; and re-epithelialisation is usually faster in SJS/TEN due to more sparing of the hair follicles in the dermal layer.46 Skin lesions can be expected to heal in an average of 15 days; oral and pharyngeal lesions may take approximately 4 weeks longer.47

Debridement of detached epidermal tissue is controversial and usually not advisable in patients who have a positive Nikolsky sign.46 Collagen sheet dressings,29 Biobrane® (Dow B. Hickam, Inc., Sugarland, Texas, USA),48 and other occlusive non-adhesive wound coverings that prevent fluid loss and minimise pain with dressing changes have been recommended. These biological dressings create a physiological interface between the wound surface and the environment that is impermeable to bacteria, thus helping to prevent local wound infection.50 In addition, the collagen sheets are non-inflammatory, facilitate fibroblast migration to the wound site, assist in extracellular matrix synthesis, are non-toxic, and minimise scarring.26

Oral topical anaesthetic gel (lignocaine 2%) and chlorhexidine mouth rinse have been used for oral lesions, and dexamethasone (0.1%) eye drops for ocular lesions.47 Post-healing, artificial tears and lubricants may be needed.46

Skin care after full closure includes use of sun screens and/or avoidance of sun exposure. Re-administration of the causative medication should also be avoided. A second episode due to the same drug may have a shorter onset than after the first episode; however, the symptoms may be more severe.51

SUMMARY

In summary, ADRs can be immediate or non-immediate, in which case symptoms will appear 1–3 weeks after the first exposure to the causative medication. The most immediate and important medical treatment involves identification and cessation of that medication. Appropriate medical and wound care is dependent upon the severity of the cutaneous and systemic reactions, and in severe cases may involve hospitalisation. The morbidity, mortality, and socioeconomic costs of ADRs are significant and further research on pathology, diagnosis, and prevention is warranted.