BACKGROUND

Lipid transfer proteins (LTPs) are allergens widespread in plant foods. They represent the main cause of food allergy in adults living in the Mediterranean Basin.1,2 The manifestation and severity of LTP hypersensitivity are extremely variable. Given the peculiarities of this allergy and the unpredictability of its clinical manifestations, epinephrine auto-injector prescription and its actual use has become an important clinical issue.

AIMS

The purpose of this study was to investigate LTPs in patients, and the actual use of prescribed epinephrine auto-injector, as well as the appropriateness of its prescription according to the European Academy of Allergy and Clinical Immunology (EAACI) guidelines.3

In addition, the authors investigated the following in patients: (1) the occurrence of new food reactions in patients with a diagnosis of LTP allergy from at least 3 years prior; (2) the number of patients requiring access to emergency services; (3) presence of possible predictive factors to additional food reactions; and (4) patient adherence to annual follow-up visits.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

The present study was carried out on 165 adult subjects with at least a 3-year prior diagnosis of LTP allergy, presenting at the outpatient Allergy Unit of IRCCS Agostino Gemelli University Policlinic, Rome, Italy, between 1st January 2018 and 31st December 2020. All data were collected by medical records.

RESULTS

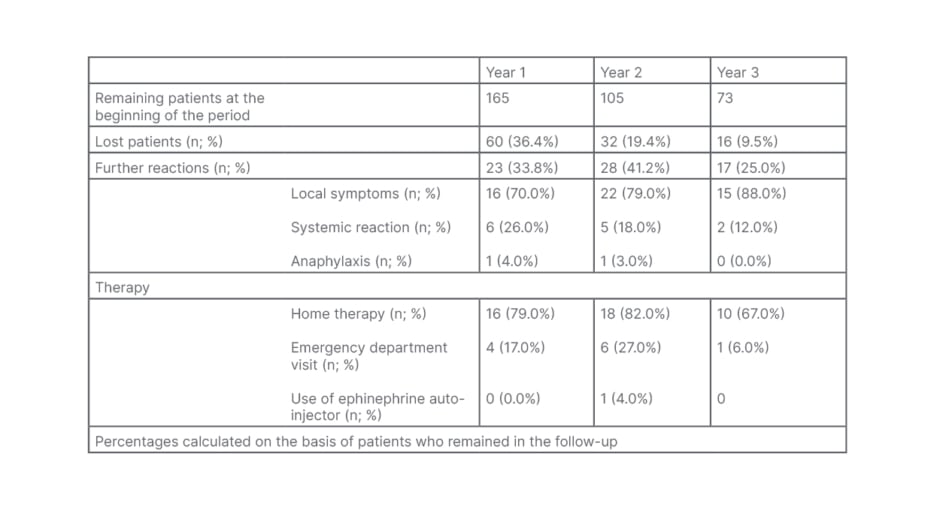

A total of 165 patients were included in the study, 110 females (66.7%) and 55 males (33.3%), with a mean age of 37.8±12.4 years. Epinephrine auto-injectors were prescribed in 108 patients (65.5%), in face of 67 (40.6%) patients having a strict indication to an ephinephrine autoinjector prescription. Based only on the clinical history, the authors recorded an epinephrine over-prescription of 25%. They monitored the onset of further reactions over the following 3 years of follow-up (Table 1), recording 68 new reactions during this time. In particular, they noted 33.8% (23 patients) had further reactions during the first year, 41.2% (28 patients) during the second year, and 25% (17 patients) during the third year. Most reactions (53/68; 77.9%) were characterised by local symptoms that promptly receded with home therapy (oral antihistamines and corticosteroid); systemic symptoms were recorded in 19.1% (13/68) cases, and 2.9% (2/68) of cases were anaphylactic. The patients rarely required an emergency department visit (16.1%), and only one patient (1.7%) used the epinephrine auto-injector whilst waiting for medical attention. Moreover, the authors observed an association between platanus pollen sensitisation (Pla a3) and severity of further reactions during the follow-up (p=0.026). Overall, 108 patients (65.5%) were lost during follow-up; 60 patients (35.7%) during the first year, 32 (19%) during the second year, and 16 (9.5%) during the third year. A large proportion of patients (86%) who attended the annual follow-up had an epinephrine auto-injector prescription. Logistic regression analysis revealed that five times more patients without epinephrine auto-injector prescription were lost, compared with patients with this prescription (p=<0.0005, hazard ratio: 5.08, 95% confidence interval: 2.2–11.7).

Table 1: Clinical severity and therapy of further reactions recorded during the follow-up.

CONCLUSIONS

The actual use of the epinephrine autoinjector alongside an incidence of severe allergic reactions seem be low in patients with LTP who had been previously diagnosed by an allergy unit. The relative epinephrine over-prescription rate could be justified by the peculiar and unpredictable features of this allergy. Further investigations would be useful to phenotype these patients, defining their risk profile and need for epinephrine autoinjector prescription, optimising individual treatment.