Food allergy poses a significant clinical and public health burden, affecting 2–10% of infants, and T cell dysfunction has been previously reported in children with food allergies. Work from this group,1 and by others,2 suggests that suboptimal T cell response capacity to mitogens and allergens is an important premorbid factor in the development of food allergies. This group has previously described differences in neonatal total CD4+ T cell activation gene-response capacity and proliferative potential in children who eventually develop food allergies in the first year of life.1 These differences are apparent at birth, an age that is unrelated to allergen exposure, and therefore of unknown clinical significance.

In the current study, this work is extended to focus on naïve CD4+ T cells, which are mature multipotent precursors with the capacity to adopt a range of different T cell effector and memory phenotypes depending on intracellular signalling factors and extracellular cytokine cues. After activation, naïve CD4+ T cells establish heritable transcriptional programmes that enable progression to short or long-lived effector or memory phenotypes. The initial phase of naïve CD4+ T cell priming involves epigenetic remodelling of chromatin, which is crucial for mounting effective immune responses and influencing T cell lineage decisions.3

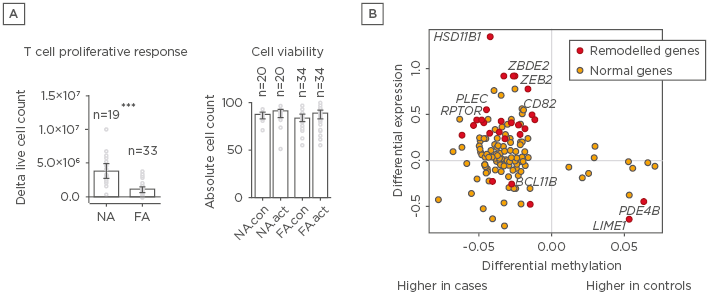

In this study, we investigated the epigenetic regulation of the naïve CD4+ T cell activation response among children with immunoglobulin E-mediated food allergies. Using integrated DNA methylation and transcriptomic profiling, it was found that food allergy in infancy was associated with dysregulation of T cell activation genes. Reduced expression of cell cycle-related targets of the E2F and MYC transcription factor networks and remodelling of DNA methylation of metabolic (RPTOR, PIK3D, MAPK1, FOXO1) and inflammatory (IL1R, IL18RAP, CD82) genes were associated with poorer T lymphoproliferative responses in infancy after polyclonal activation of the T cell receptor (Figure 1). These molecular changes associated with food allergy were revealed post-activation and were not detectable in quiescent cells. Infants who failed to resolve food allergy in later childhood exhibited cumulative increases in epigenetic disruption at T cell activation genes and poorer lymphoproliferative responses compared to children who resolved food allergy.

Figure 1: A) Depictions of proliferation responses and T cell activation and B) methylation and gene expressions for individuals with and without food allergy.

A) Proliferative responses and cell viability following T cell activation. Data are expressed as fold-change calculated as post and preactivation cell counts, with bars showing median and interquartile range. Groups were compared using the Mann–Whitney test. B) Relationship between differential methylation and gene expression. X-axis shows delta value expressed as percent methylation (10-2) for the comparison of cases and controls. Y-axis shows the log2 fold-change. Points in red were differentially methylated and expressed (remodelled genes) at the genome-wide level.

FA: food allergy; FA.act: food allergy activated; FA.con: food allergy quiescent; NA: nonallergic; NA.act: nonallergic activated; NA.con: nonallergic quiescent.

***p<0.001.

These data indicate that gene–environment interactions mediated through epigenetic changes associated with food allergy overlap T cell activation pathways.