Non-adherence to medication can be caused by a range of factors, including unconscious biases. Pharma companies can tackle this challenge by reworking current models to ensure they are connecting with patients’ personal motivations and individual biases

Words by Isabel O’Brien

Playing out against a musical backdrop of grunge, rave and hip hop, the 90s was a decade defined by progress and discovery. Not only did the iconic Nokia 1011 hit the market as the first mass-produced mobile phone, Google came online for the first time. The way people consumed and communicated information changed forever.

Alongside these cultural and technological revolutions, two psychologists, Mahzarin Banaji and Anthony Greenwald, sought to build on existing research to decode why people choose to undertake certain behaviours – particularly seeking to unpack the unconscious motivations behind decision-making.

In 1995, the duo coined the phrase ‘implicit bias’, which describes attitudes or stereotypes that affect people’s understanding, actions and decisions in an unconscious way. Today, the theory is also known as ‘unconscious bias’ or ‘implicit social cognition’, and the concept can go a long way to explain why many people struggle to make positive decisions in relation to their health.

The more biases you have, the more cognitive friction there is. It’s like you can’t get out of your own way

“In the last few years, there has been a lot of attention regarding unconscious bias as it relates to diversity and inclusion,” says Dr Peter Piliero, Vice President, Medical Affairs, Melinta Therapeutics. “However, I don’t think patients’ unconscious biases about their condition leading to impacting inertia is well understood by the pharmaceutical industry.”

Indeed, the industry is at the very start of a journey to understand how unconscious influences could be impacting adherence within different patient populations, but enormous potential could be unlocked if pharma can start tapping into personal motivations and individual biases with its activities.

Types of unconscious bias

“Unconscious biases are incredibly prevalent in non-adherence,” says Katy Irving, Global Head of Behavioural Science, Healthcare Research Worldwide. She highlights the two key strains of non-adherence: intentional and non-intentional, explaining that while each type is separated by distinct differences, unconscious bias can play a significant role in both.

Intentional non-adherence could be triggered by an authority bias, where a person doubts the credibility of medical advice and therefore refuses to follow the recommended treatment regimen. “This may appear as people not considering their doctor or the pharma industry as a credible source and therefore distrusting the recommendations,” Irving clarifies.

Likewise, in non-intentional non-adherence, an optimism bias could be an influencing factor. This involves a patient believing their condition is less severe than it really is. “This bias leads patients to underestimate the risk posed by their condition overall and therefore lack urgency to adhere to treatment,” Irving continues.

Other biases include: ego threat, defined by a struggle to see oneself as a patient; learned helplessness, characterised by a sense of burnout due to the obstacles of chronic illness; the appeal to nature fallacy, which stems from a belief that natural treatments are ‘good’ and unnatural ones are ‘bad’; and feedback loops, where the brain needs a reward to complete a treatment regularly and successfully.

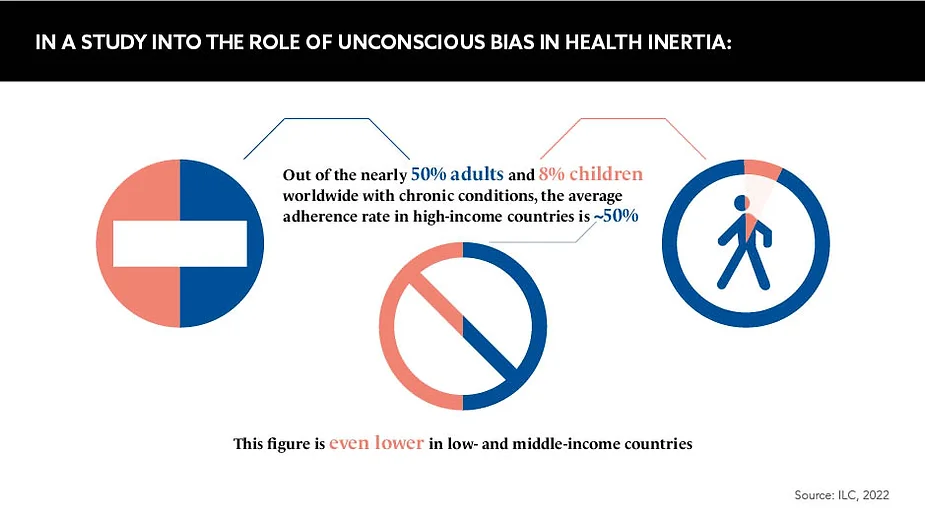

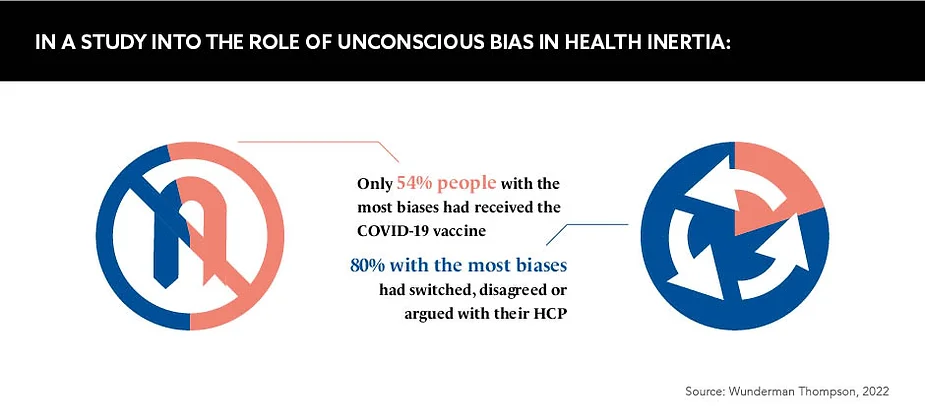

People living with chronic conditions are likely to have several of these biases about their health, according to Wunderman Thompson’s 2021 Health Inertia report, which examined the biases of people with conditions ranging from cancer to depression. Michael Duke, Chief Data and Analytics Officer, Wunderman Thompson Health, who worked on the project, reveals: “The more biases you have, the more cognitive friction there is. It’s like you can’t get out of your own way.”

The same pattern was observed across different disease areas – even in routine health care decisions, such as whether to get vaccinated. “We saw that people who have more cognitive biases were less likely to have got the COVID-19 vaccine,” adds Mark Truss, Chief Research Officer, Wunderman Thompson Data. He also reveals that only 2% of people they studied exhibited no signs of unconscious bias.

The associated challenges

It is clear that unconscious bias is both a prevalent and influential factor in non-adherence, but the question remains as to how the pharmaceutical industry can address a problem that, in most cases, even patients themselves are unaware of.

“It’s difficult for patients to directly report when non-conscious factors are at play,” says Irving. The measures that pharma typically relies on to understand non-adherence are inadequate in this context because “they rely on self-reporting, so stop short of uncovering the role of non-conscious factors”, she adds.

The logical solution, then, would be to step up education initiatives about the role unconscious bias can play. But, as Trishna Bharadia, Consultant on Patient Engagement, Chronic Illness, Disability and Diversity, points out: “No amount of education is going to change someone’s thinking.” This is a widely held view, with Duke stating: “Education doesn’t always work. Education does not motivate.”

Unconscious bias is a complex factor in non-adherence that is easier to influence than a patient’s socio-economic status or systemic failures in the healthcare system, but it is a challenge that continues to trouble the industry as a whole.

Influencing unconscious bias

For most pharma companies, better segmentation could be the answer. Much like HCPs are divided and conquered, they could seek to segment patients by bias type and create activities to target each.

For example, Irving suggests that companies could harness the power of patient influencers to appeal to those with authority biases. By enabling them to “leverage the social proof that comes from their peers”, they turn the power dynamic on its head. Messaging could also be reworked to adopt a “gentle and approachable tone”, she adds, stressing the importance of communicating the risks of medicines in a “positive and non-scary way” to address biases such as ego threat, optimism bias and learned helplessness.

“Pharma companies have to start working on this,” urges Truss. “Understanding it, studying it and bringing in experts who know this space and what it means relative to healthcare.”

Missing a trick

Reflecting on the adherence challenge overall, Caitlin Rich, Medical Consulting and Patient Partnerships, VMLY&R Health, says: “Lack of adherence leads to worse outcomes, and although this is not the fault of the product, it leads to patients and doctors losing faith in a product and switching to another, so the industry loses the business.”

If unconscious bias is as prevalent as research suggests, the pharma industry is missing a trick by sticking their head in the sand. Unconscious bias may have only entered the world’s vocabulary in the last 30 years, but people have been under the influence of these unconscious forces since time immemorial.