Exploring the pharmaceutical landscape in South Africa, GOLD considers several areas that are shaping the nation’s role in the future of global pharmaceuticals

Words by Cheyenne Eugene

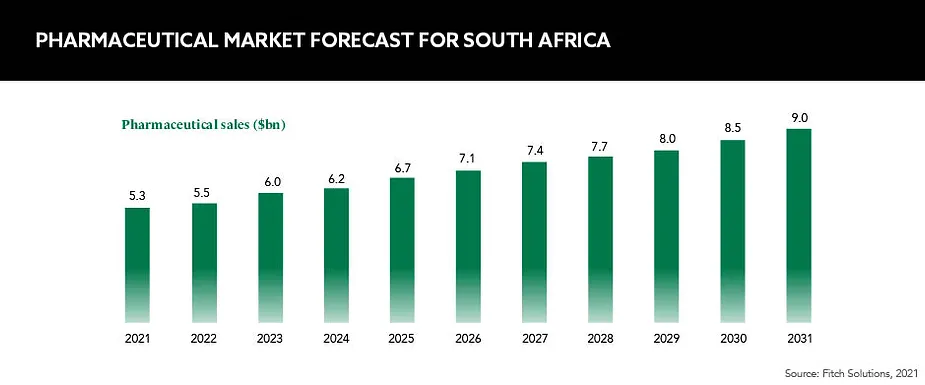

South Africa is one of the pharmaceutical leaders on the African continent and is considered to be one of 21 global pharmerging markets by IQVIA – those that have a low position within the global pharma market but are enjoying a high pace of growth. Currently, the South African market is dominated by generic drugs and its manufacturing capabilities, but is this set to shift?

The South African government has had a rocky relationship with the global pharmaceutical industry. This came to a head when the government signed the Medicines and Related Substances Control Amendment Act in 1997 in a bid to import generic versions of branded antiretrovirals for HIV.

The following year, 39 pharma companies waged a legal battle with the South African government, arguing that the law infringed on patent rights, and reportedly cancelled investments in the country and closed factories. After years of public outcry worldwide, the pharma companies agreed to drop the lawsuit in 2001, and a renewed relationship between the two entities began.

South Africa remains the epicentre of the modern-day AIDS epidemic, yet its resoluteness to treat its population and eradicate HIV has been instrumental in cultivating a high-tech hub primed for the distribution and manufacturing of pharmaceuticals.

Market access issues

One challenge seen confronting the nation’s pharma industry is its access to the international market. Lenias Hwenda, Founder and CEO, Medicines for Africa, explains that South African companies have limited access to international market channels, such as those run by multilateral organisations like Gavi, the Vaccine Alliance and UNICEF. “Because these international markets are buying for most of the countries on the African continent, when they don’t buy from domestic manufacturers, this limits the access by South African companies to the African market as well,” she says.

Many innovative MNCs look at South Africa as a ‘regional hub’

Overcoming this on a local level, Hwenda suggests that the South African government use public procurement to recalibrate its market and provide greater protection for domestic manufacturers. Leveraging regional structures, such as the African Continental Free Trade Agreement, may also help to harmonise the African market.

“African countries need to have a conversation with international organisations that control the African market to make sure that they procure medications in a way that does not exclude [African] manufacturers,” says Hwenda. Protecting South African manufacturers is vital for strengthening both local and global supply chains and securing national access to medicines during health crises, such as pandemics.

Intellectual property

Another challenge of particular significance is the protection of intellectual property (IP). As the largest pharma market in sub-Saharan Africa, South Africa has a big stake in the pharma sector. “Ensuring strong IP protections will be fundamental to fostering South Africa’s biopharmaceutical sector, and, in turn, achieving the government’s goals of increasing local production of pharmaceuticals to meet domestic needs, as well as creating export opportunities within the continent and beyond,” explains Bada Pharasi, CEO, Innovative Pharmaceutical Association of South Africa (IPASA).

IP is particularly important for promoting the development of new technologies such as biologics, which may not be adequately protected by patents alone. “Strong IP protections increase opportunities for clinical research, which improves medical research infrastructure and provides opportunities for growth,” Pharasi adds, and this benefits both South African companies and patients.

Reforms and strategy

In June 2017, South Africa’s drug regulatory agency was replaced with a modernised alternative – the South African Health Product Regulatory Authority (SAHPRA). This was created with the aim of streamlining South Africa’s regulatory process and with the initial task of getting its teeth stuck into a staggering backlog of almost 16,000 drug applications accumulated by its predecessor.

Although the impact of this backlog, containing applications dating back as far as 1992, is still looming over the SAHPRA, the body has a clear strategy and is working collaboratively to wipe the slate clean. Already, thousands of applications have been liberated from the long queue and those still remaining are being prioritised based on public health needs.

The coming into effect of the NHI is likely to significantly increase the consumption of medicines

In 2012, a promising National Health Insurance (NHI) Bill was passed by the South African government, with a plan to implement its objectives in three phases over the following 14 years. Having the aim of modernising healthcare across the nation, the NHI functions as a health financing system that is designed to pool funds and buy services on behalf of the entire population. This funding comes via a combination of various mandatory prepayment sources, primarily based on general taxes. The NHI, much like the UK’s NHS, hopes to provide access to quality, affordable and personal health services for all South Africans based on their individual health needs, irrespective of their socio-economic status.

Such an ambitious and broad system is of great significance to the global pharma industry. “The coming into effect of the NHI is likely to significantly increase the consumption of medicines,” Hwenda tells GOLD. “Policymakers are contemplating how the increased demand could be leveraged to enhance domestic supply to the majority of the country’s needs and to make South Africa a globally competitive pharmaceutical industry.”

Pharasi suggests that certain provisions of the NHI Bill, particularly around the pricing and procurement of medicines, “may affect sustainability of the industry as a source of innovative medicines to the South African population”. He says: “The growing incidence of diseases such as cancer will also likely result in the increased use of patented medications including biologics, but I expect the national health insurance will be concerned about the cost and affordability, which will affect what the government is willing and able to buy in order to treat the maximum number of people.”

The IPASA, along with other stakeholders, has submitted its views to Parliament’s Portfolio Committee on Health, which is “expected to re-publish the Bill at some stage, hopefully with amendments demonstrating that our views have been taken into consideration”.

Future and opportunity

There are specific facets of South Africa’s pharma industry that are breaching the horizon and bringing with them great promise for the nation’s status as a pharmaceutical powerhouse. The first is the country’s emerging biotechnology sector.

Biotech companies emerging in South Africa are not only expected to contribute to the global value chain by creating a selection of new pharmaceutical products, but also by developing diagnostics and active ingredients for global markets. “A number of South African biotech companies involved in formulation and bioprospecting are likely to develop into important strategic sources of pharmaceutical ingredients for the African and global pharma industry,” confirms Hwenda.

Another promising portion of the nation’s potential lies with genetics. “South Africa has world-class genomic sequencing and genomic surveillance infrastructure that will make it likely to contribute significantly to global pharma in the future,” says Hwenda. The region is already contributing to genomic surveillance, and Hwenda explains that this is critical for global outbreak responses and product development.

Overall, South Africa’s future within global pharma is bright. “The investment landscape looks very attractive at the moment because of the tremendous opportunity that the South African market presents both in its own right but also as a gateway to the rest of the continent,” explains Hwenda. This is reiterated by Pharasi, who says: “Many innovative multinational corporations (MNCs) look at South Africa as a regional hub for managing pan-African commercial operations and centralising functions.” By encouraging MNCs to base their regional headquarters in South Africa, the socio-economic benefits could even outweigh the South African market value, he says, “with enhanced employment, knowledge transfer and investment value into the country”.

As part of its commitment to establishing a competitive environment, “the government has put its money where its mouth is”, and is focusing on programmes that promote local R&D and manufacturing, Hwenda explains. Hubs for regional R&D and manufacturing can expand the availability of drugs, lower costs and strengthen local health systems, leaving the country less reliant on imports and able to leverage local demand.

South Africa has no desire to be an island and it is encouraging MNCs to invest in its future as an innovation hub, a dependable manufacturer and as a channel into the rest of the continent. With its rigorous regulatory reforms and nascent NHI, it’s clear that the nation is serious about defining its place on pharma’s global stage.