Poland is somewhat of an unsung hero on the international pharma stage, but it is the emerging star of eastern Europe. Why is Poland’s pharma market flourishing, what challenges are being faced and what’s the future outlook?

Words by Isabel O’Brien

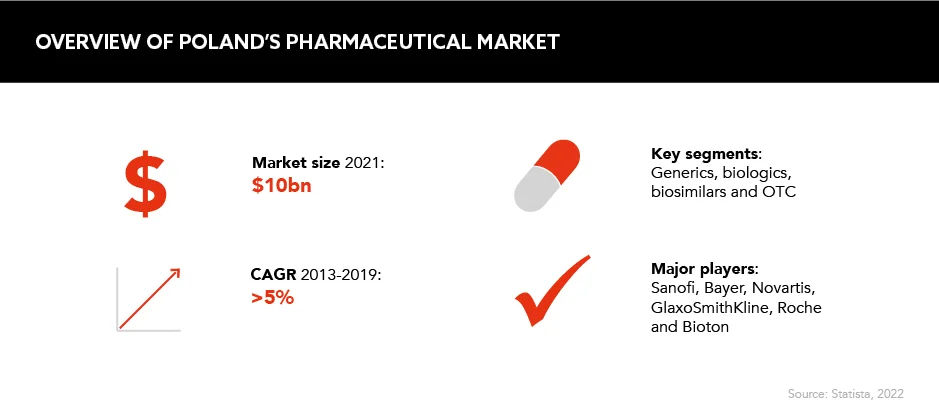

As the fifth largest pharmaceutical market in the EU – ranking after Germany, France, Italy and Spain – Poland’s life sciences sector is growing at a quicker pace than any other country in central and eastern Europe (CEE). The industry’s value was pinpointed at 10bn USD in 2021, and Poland has been dubbed a ‘pharmerging’ nation by IQVIA.

This term was coined in 2021 and describes countries with a low GDP and rapidly expanding pharma sector. Poland is one of the few European countries to feature on the list of 22, but others include China, South Africa, Brazil and India.

So, why is this? Sebastian Cudny, Former General Manager Poland, Ukraine and Baltic Countries, Ferring Pharmaceuticals, has a few ideas. “Poland is a pharmerging country because of its potential,” he begins. “We have 38 million inhabitants; we contribute more and more every year to healthcare, and we can copay for products.”

As it stands, the pharma industry contributes 1.7% to Poland’s overall GDP

Indeed, many pharmerging nations have large populations, meaning plenty of patients to treat with products and participate in clinical trials, plus the population’s willingness to invest in their healthcare creates further clout. On the flip side, however, copayment implies access to medicine issues, which is another commonality among pharmerging countries, and places risk on their future success if this is not dealt with appropriately.

So, while Poland’s pharma sector holds promise, there are certainly challenges facing its future growth.

An economic hub

A key driver of Poland’s up-and-coming pharma status is its healthy economy. According to the World Bank, the country has the highest GDP in CEE, and it contributed the lion’s share to total GDP for the region in 2021 – totalling 679.4bn USD. The figure is low in comparison to western Europe, but it clearly shows that Poland is more financially secure than its neighbours. For example, the Czech Republic and Ukraine only made around a third each of what Poland did in 2021. Their GDPs totalled 281.1bn USD and 200.1bn USD respectively.

The nation is also the largest beneficiary of the EU’s Cohesion Fund – an initiative offering financial support to member states with a gross national income per capita below 90%. The fund has pledged €160bn in subsidies and loans to Poland until 2027, which was allocated after the UK exited the EU in 2020.

Such economic stability provides internal resources for local pharma companies, but it also positions Poland as an attractive destination for foreign investment. As it stands, the pharma industry contributes 1.7% to Poland’s overall GDP.

Domestic pharma firms

Like many other pharmerging nations, “the Polish pharmaceutical industry is based mainly on producers of generic and bio-substitutes”, says Magdalena Bojko, Former Senior Regional Manager, Cross-functional Medical, Marketing and Compliance Role, Biogen. One of its oldest firms, Polpharma, is one of the top 20 generics producers globally and dates back to 1935.

According to Cudny, though, the local pharma sector in Poland didn’t truly prosper until “the moment when communism ended”, which was after the Revolutions of 1989, in which uprisings began in Kazakhstan and spread across eastern Europe.

The pharmaceutical market in Poland is one of the most strategic industries in the country

Indeed, several new firms have sprung up since the late 1980s, including a notable boom in the number of biotechnology firms. Bioton is one biotech company of note. It is one of the top eight manufacturers of recombinant human insulin in the world and sells its products internationally.

Still, the Polish government is ambitious for further growth. Following Bioton and other biotechs’ successes, the government is seeking to transform the country into a regional leader in biotechnology. How? In March 2022, it announced plans to create a more investor-friendly ecosystem and promote innovation through new laws and financing programmes.

In addition, researchers applying for funding for the domestic production of generic or biosimilar medicines will receive a grant of 150 million Polish złoty, worth 31.2m USD, as part of the plan, showing the government’s continued dedication to expansion in this area.

“The pharmaceutical market in Poland is one of the most strategic industries in the country,” confirms Bojko. “It is considered one of the most innovative.”

International players

Poland has attracted a variety of foreign pharma companies to establish offices within its borders, including five of the top 10 global pharma firms: Sanofi, Bayer, Novartis, GlaxoSmithKline and Roche.

This international presence has injected vital funds into the country’s pharma sector, as well as contributing to the 100,000 jobs that have been created directly and indirectly by the industry for Polish citizens. Despite this success, Poland is keen to attract additional investment from companies based overseas.

The US is a particular target, and Poland has announced plans to emulate the US medical model with a 10-year development strategy. The nation hopes to attract more US players by adapting its regulatory and commercialisation landscape to become a more attractive location for innovative drug makers to set up a home.

Access to medicine

While this is all largely positive, Poland’s access to medicine framework is considered substandard, particularly for a country hell-bent on expansion. “Affordability and unmet medical needs are key concerns in Poland,” says Bojko. While not an exhaustive list, the main issues link to drug costs and the number of medical staff in the healthcare system.

“The biggest challenge is the price of the product,” offers Cudny. “In Poland, purchase power is lower compared to the EU, but prices remain the same.”

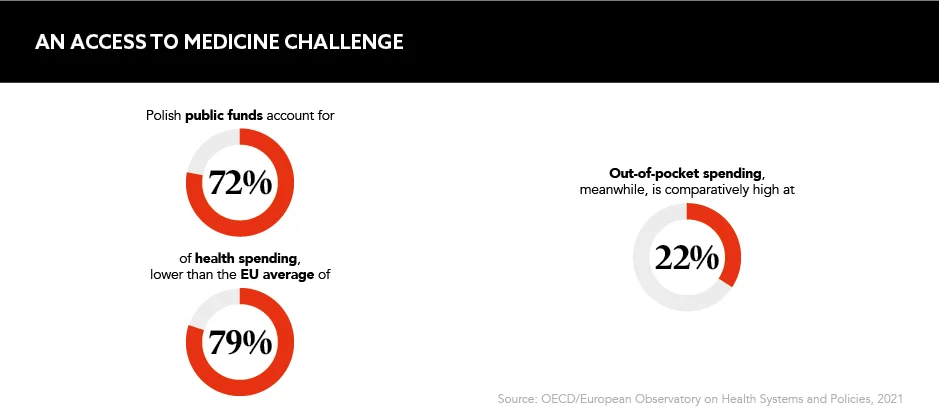

He believes product prices should be reduced in Poland compared to western Europe. Within the current system, the government can only cover 72% of overall medical spend. Not only is this below the EU average, it is the reason out-of-pocket spending for the public is high.

A shortage of healthcare professionals is driving access levels lower still. “The availability of services is constrained by the low number of healthcare practitioners,” confirms Bojko. “The result is that Poland has the longest waiting times in the EU for [certain] healthcare interventions.” For example, the average wait for an MRI medical examination amounted to 51 days in January 2022.

Clearly, pricing reform and higher numbers of physicians, nurses and other HCPs are urgently needed in Poland, but the latter challenge may have at least a temporary solution.

Some eight million people have fled to Poland since the Russia-Ukraine conflict began in February 2022, with many settling in the country and looking likely to stay. To put this figure into context, “it’s [roughly equivalent to] 20% of the total population in Poland”, says Cudny. Migration has been tough for those displaced, and for Poland, but it isn’t all doom and gloom for either party.

At least for now, there is a positive by-product of the influx: refugees have gained access to free healthcare, and Poland’s healthcare system is being boosted as Ukrainian healthcare professionals sign up to the workforce. This could offer temporary respite from shortages, but only time will tell if the increase in population size will taper improvements.

The bottom line

Poland’s pursuit of pharmerging status is proving rocky but ambitious. It could falter due to its access to medicine issues, but the government is showing willingness to evolve and rethink its approaches to raise more capital for its healthcare system. The country is certainly the most promising market in the CEE region, and it has the potential to hold onto this acclaim for the foreseeable future.