GOLD travels to the bustling shores of India, known by some as ‘the pharmacy of the world’. But what has shaped this company’s ascension to pharmaceutical powerhouse status, and what access challenges exist across its wide expanse?

Words by Jade Williams

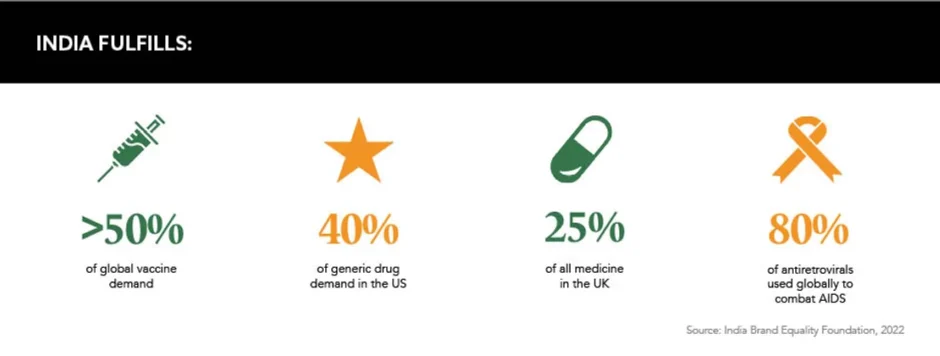

India: the home of colour. From the Ganges to the Himalayas, to Holi festival and cricket, this diverse nation is also a striking pharmaceutical powerhouse and stands, by far, as one of the largest. With an estimated value of $42 billion in 2021, India holds the impressive title of the world’s largest provider of generic medicines and is the biggest vaccine supplier on the planet.

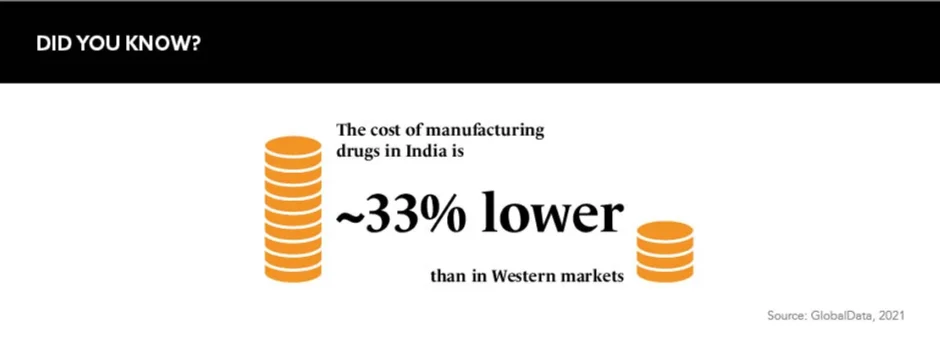

The country has a rich and varied history in pharma, and many multinational companies outsource their manufacturing processes to India, making use of the low-cost services associated with the country and its prime location for active pharmaceutical ingredient procurement

India serves as the base of operations for over 3,000 drug companies and around 10,500 manufacturing units

Known by some as ‘the pharmacy of the world’, the vibrant and bustling landscape of India serves as the base of operations for “over 3,000 drug companies and around 10,500 manufacturing units”, according to Ulrich Deutschmann, Chief Commercial Officer, DFE Pharma. The wide expanse of the country houses a plethora of large pharma companies including Sun Pharma, Divi’s Laboratories, Cipla, Dr Reddy’s Laboratories. And many more companies are opening additional facilities, such as DFE Pharma’s new India-based Center of Excellence providing fast-track formulation services from product conception to successful commercialisation.

“Many countries look to India as a major emerging market with its population approaching 1.5 billion, of which a larger proportion are entering the middle class,” comments James Hazel, Research Programme Manager, Access to Medicine Foundation. “Some figures state that by 2027 the country will have a larger middle class than the US, China and Europe.” This rapidly evolving population positions India as an ideal base for operations and an increasingly attractive and lucrative consumer market for pharma.

A generics giant

When it comes to India’s main strength and differentiator, Hazel states: “The enlarged generics market in India certainly sets it apart from its counterparts.” Indeed, India was able to build a sizeable generics market because patent laws were only present in the country for the production processes, rather than the finished product. This was until 1995 when the Agreement on Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights – or TRIPS agreement – was introduced to all member nations of the World Trade Organization (WTO) and adversity hit the market. This agreement, which is still in place, seeks to protect patent status for innovative pharma companies’ novel products for 20 years in order to prevent generic versions reaching production stages before a patent expires.

Hazel notes that “before this agreement was enforced, India only had patent laws on the production process” for drug manufacturing, meaning that if another route to produce the medicine was found, any potential claims could be circumvented. As a result, India had the ability to develop its generics market exponentially until the new patent law was enforced. The country was, however, granted a grace period until 2005 to take the necessary measures to ease this transition, in which India was given a three-stage framework for strengthening its intellectual property regime.

The enlarged generics market in India certainly sets it apart from its counterparts

Despite the TRIPS agreement initially acting as a setback for the country, R&D investments by Indian firms increased rapidly as a result. Its global enforcement spurred companies to focus more of their efforts on R&D to discover more novel drugs. In 2020, however, conflicts re-emerged over patents.

Covid response

In 2020, India, along with South Africa, proposed that the WTO grant a temporary waiver on the TRIPS agreement to allow for more widespread production of COVID-19 vaccines that would allow the nations to manufacture their own. More than 100 developing countries supported this endeavour, but G7 members decided to stop it in its tracks, meeting scrutiny and criticism from organisations including Médecins Sans Frontières and the European Parliament.

While this was not granted, India did eventually purchase vaccines in their worldwide rollout as of January 2021. The country then kicked off its own international shipment just four days after starting this vaccination programme, sending free doses to Bangladesh, Nepal, Bhutan and Maldives – 3.2 million doses in total.

“One of the impacts of COVID-19 has been the creation of a strong demand for medicines and local manufacturing,” comments Deutschmann. If a novel pandemic were to rear its ugly head again, he expects “a strong focus on issues such as security of supply” and encourages the industry to set in place “more resilient supply chains” to combat the production and access bottlenecks witnessed in 2020.

Despite this renewed focus on local manufacturing, Hazel highlights that not all regions within India were able to achieve sufficient access to vaccines. “Unfortunately, we did not see that equitable distribution this time around. In a future pandemic, I do however think India could certainly play a better role,” he says.

Health disparities

With a country as large and diverse as India, it is hardly surprising that a huge proportion of the population does not have equitable access to medicines. In rural towns and villages, accessibility, quality of treatment and affordability are lacking. Hazel laments that “companies will say that they could provide their medicine at cost or even donate it free of charge to a country, but this does not necessarily mean that it would reach patients” in lesser developed regions. These products may end up being distributed to larger towns and cities where people can generally already afford to pay health expenses, leaving those in more rural areas high and dry.

Pharma companies are uniquely positioned to have a positive impact in the regions they export to, and Hazel urges companies sending products to India to look beyond the big cities. He comments that “there is a question about what role companies themselves have in terms of strengthening healthcare systems versus governments, NGOs and funders”. If they engaged more with capacity building and health system strengthening in India’s rural areas, they could help to greatly improve the nation’s health disparities. Half of India’s population is receiving some of the best pharmaceutical offerings the world can provide, while the remainder have access to very little.

India has one of the highest levels of AMR

Fatema Rafiqi, Research Programme Manager, Access to Medicine Foundation, alongside Hazel, offers her perspective on India’s antimicrobial resistance (AMR) struggles. “While the Indian population is one of the biggest consumers of antibiotics, it is also important to understand that they are not getting access to the right medicines,” she says. Indeed, India has one of the highest levels of AMR because of readily available over-the-counter antimicrobials, which give way to misuse, plus the inadequate treatment of wastewater. While efforts to combat this have been initiated, they remain at preliminary stages.

A hopeful future

While the pharma industry in this dynamic region of the world is a strong and prevalent force, there is much to iron out in the finer details of its colourful landscape. Despite being one of the largest manufacturers of modern medicines, it falls short of the mark in providing adequate access to the right medicines to India’s ever-growing and dispersed population. However, one thing is certain, according to Hazel: “India is going to continue to be a leader in generics and manufacturing.”

With some fine-tuning, advantageous governmental policies and access campaigns, India could progress to become not only the pharmacy of the world but one of the world’s greatest pharma stages.