Landmark science has provided ample opportunity for new transformative therapies, but concern is mounting about how the market can sustain the huge number of products being developed in some areas. So what might the future hold?

Words by Danny Buckland

Stampedes start with a murmur then gather an irresistible pace, and cell therapy is rapidly becoming the pharmaceutical industry’s runaway success, as well as a beacon of hope for the treatment of cancers and rare diseases.

Ground-breaking discoveries in 2006 revealed that stem cells could be reprogrammed genetically, and fired-up research teams got to work. They created a range of therapies – treating diseases from multiple sclerosis to macular degeneration – and also worked out how to re-engineer T cells to target and fight cancers to create a revolutionary landscape for immunotherapy.

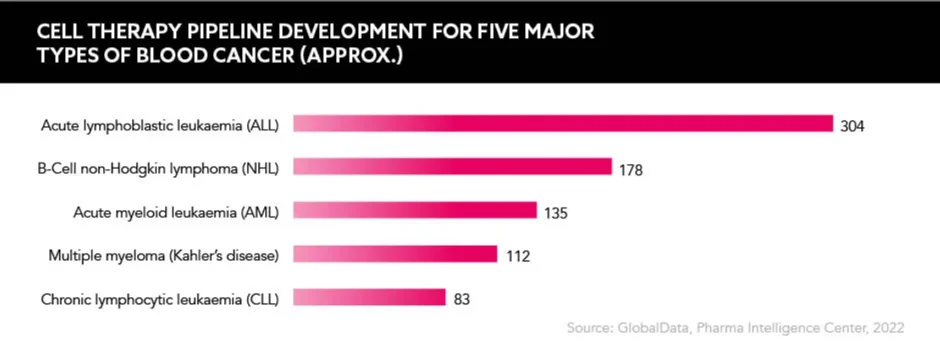

The surge of cell and gene therapy (CGT) is impressive; more than 800 cell therapy products are in development for the blood cancer market alone, and more than 500 CAR-T clinical trials are running in this space. But this success is ringing alarm bells on how approval, reimbursement and commercial models will be impacted.

A report from GlobalData warned that the blood cancer market could not sustain an oversaturated cell therapy pipeline. “Cell therapies have seen some strong successes in the oncology market, with Gilead’s Yescarta and Novartis’ Kymriah paving the way for other developers to build upon the success of their chimeric antigen receptor T cells (CAR-T) cells,” states Sakis Paliouras, Managing Oncology and Haematology Analyst, GlobalData.

Success has brought about an abundance of products in development

“However, this success has brought about an abundance of products in development,” he continues. “Oncology is unlike other therapy areas such as cardiology or immunology, where the commercialisation of a large number of products with similar attributes is the norm. If all of the in-development drugs for blood cancer got the go-ahead from the FDA, competition would be much too fierce.”

Navigating concerns

GlobalData forecasts that the market for cell therapies in oncology will reach $37bn globally by 2028. The challenge is to create a platform for transformative science; easy in sentiment but much harder in practice, particularly with the manufacturing processes needed to take complex and personalised chemistry through to a medicine that can be stable enough to deliver.

The ‘Horizon: Cell and Gene Therapy’ report, compiled by the life science design, engineering, construction and consulting firm CRB, highlights concern among leading manufacturers around how they can navigate the regulatory environment, design new production lines, pivot to small batch delivery – sometimes for just one patient – finance new lines and secure a skilled workforce.

A critical choke point will be cost as CGTs are expensive to research, develop and produce and the returns, as they often apply to small patient populations, are limited. “High costs make CGTs economically unviable and inaccessible to patients. Government and insurers are expected to pay for these therapies, and, in the value-based model, manufacturers share the burden,” explains Surbhi Gupta, Senior Industry Analyst, Healthcare and Life Sciences, Frost & Sullivan. “However, as a growing number of CGTs are expected to enter the market, the financial burden will increase on the government and payers, and it will become increasingly difficult for manufacturers to demonstrate value and achieve financial viability.”

Significant investment is still raining down on the market with big players swooping for start-ups and small-to-medium-sized biotechs who are trail-blazing technology, but Gupta detects a “weaker investor sentiment” this year.

Cream of the crop

Funding issues will become increasingly evident as projects are paused or pulled because their similarity to other products limits revenue potential, according to Paliouras, who adds: “It is likely that moving forward investors will choose to only fund the absolute cream of the crop of cell therapies, rather than taking a larger number of bets with predictable or me-too approaches.” Patient groups are hoping that the promise of transformative treatments, and in some cases cures, does not get clogged up in the rush to market.

A dominance of blood cancers in CGT is expected because the current main treatment option is chemotherapy, says Sarah McDonald, Deputy Director of Research, Blood Cancer UK – the charity that has invested more than £500 million in blood cancer research.

I wouldn’t say cell therapy is a victim of its own success, but it depends on which metrics we are looking at

“In the majority of cases, you can’t take it out or zap it with radiotherapy so the only progress for patients is new treatments and we are now in a zone where there is more and better science and therefore more treatments,” she says. “But it is important to recognise that blood cancer is not just one disease. It is a category of its own with many sub-types.”

The blood cancer market will be watched with acute interest as its pipeline passes through Phase 3 trials and regulators refine approvals and reimbursement protocols that will dictate which products get to market.

Is it boom then bust? “I wouldn’t say cell therapy is a victim of its own success, but it depends on which metrics we are looking at,” Paliouras observes. “If you look at it from a patient perspective, patients have already benefitted and will continue to benefit from amazing drugs that have offered new options in hard-to-treat cancers with many patients going all the way to being cured. If you look at it from a market perspective, or investor funds perspective, then yes, early cell therapy success has led to a mini-frenzy of R&D activity that has no other option than to settle down over time as the market cannot sustain it.”