Meeting Summary

Revision Notice: This article was first published online on 7th June 2018. It was revised on 8th June 2018. The full list of revisions can be seen here.

This publication covers the first session of Almirall’s 11th Skin Academy meeting in Barcelona, Spain. This year, the meeting theme was ‘The Science of Skin’. The meeting included updates in systemic and biologic therapies for psoriasis and new developments in the treatment of skin cancer, as well as hot topics such as onychomycosis and hair loss. In this first session, Prof Thaçi and Prof Augustin reviewed advances in the systemic treatment of psoriasis and explored how successful development of new treatments has led to an improved understanding of underlying disease processes. With a particular focus on the history of treatment with fumaric acid esters (FAE), the speakers explored the impact of the introduction of dimethylfumarate (DMF) monotherapy on knowledge of psoriasis and its treatment. Other topics included the complexities of treatment selection, the importance of meeting patients’ expectations, and the significant role that biomarkers and personalised medicine will have in future treatment decisions.

Treating Psoriasis

Professor Diamant Thaçi and Professor Matthias Augustin

Treatment History

Psoriasis has been treated by physicians for thousands of years, with evidence suggesting that the use of topical treatments and sunlight therapy dates back as far as the ancient Egyptians and Greeks.1 Despite this long history, the first effective treatments were not identified until the early 20th century. The development of ultraviolet (UV) phototherapy for skin diseases won a Nobel Prize in 1903, with its use in psoriasis first described in 1925; however, it was not regularly used as a treatment until the 1950s.1,2 The prevalence of syphilis during this time meant that dermatologists often also specialised in venerology, and with more patients dying of syphilis than cancer, new treatments were urgently sought. A breakthrough came in 1917 with the identification of arsphenamine, an arsenic-based compound that became the first parentally administered treatment in dermatology and venerology.3 Dermatology has since become a distinct specialism and huge advances have been made in understanding and treating dermatological conditions, including psoriasis.

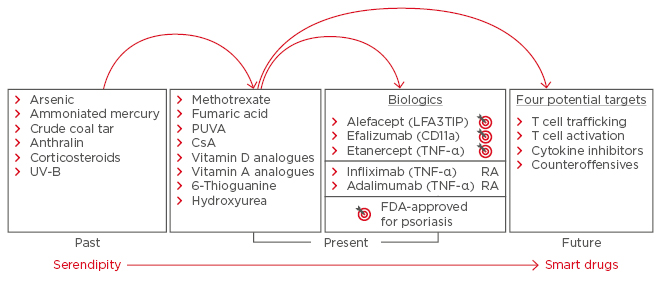

Today, psoriasis is thought to affect between 0.5% and 11.4% of the population;4 however, a wide variation in presentation complicates treatment identification and selection. Differences in severity and location of skin symptoms, and the presence of a variety of related comorbid conditions, means that treatments are not equally effective for all patients. Although environmental factors are involved in the pathogenesis of psoriasis, particularly in older patients, research has revealed an important genetic component. Among cases occurring before the age of 20 years, approximately 50% have a genetic cause, and an abundance of genes are known to be involved, with 16 new loci identified in recent years.5 Most of the identified genes are involved in the differentiation and regulation of lymphocytes, but others are responsible for responses to stimuli, regulation of adaptive immune responses, and other signalling pathways.5 These discoveries have linked psoriasis with other inflammatory diseases, including inflammatory bowel disease and arthritis, and revealed that psoriasis is much more complicated than originally thought.6 In the past 20 years, the introduction of new systemic and biologic medicines has changed the treatment landscape for psoriasis and further improved the understanding of underlying disease processes (Figure 1).7 Treatment with tumour necrosis factor (TNF) inhibitors led to psoriasis being considered as a systemic disorder and broadened understanding of the disease processes.8,9 Today, a wide range of treatment options are available to patients presenting with mild-to-severe disease, including topical therapies, phototherapy, and systemic and biologic medicines.

Figure 1: Developments in psoriasis treatment, from arsenic to biologics.

CsA: cyclosporin A; FDA: U.S. Food and Drug Administration; PUVA: photochemotherapy; RA: rheumatoid arthritis; TNF: tumour necrosis factor; UV-B: ultraviolet-B.

Adapted from Nickoloff and Nestle.7

Treatment Selection and Guidelines: Meeting Patient Expectations

The increase in the availability of effective therapies in recent years has improved the outlook for patients, but it poses a challenge for dermatologists in selecting the most appropriate treatment for each patient and has resulted in a need for frequent updates to treatment guidelines. Analysis of the German PsoBest registry, the main registry of systemic treatments for psoriasis, found that during 2015–2016, the most frequently prescribed systemic treatments were FAE, followed by methotrexate and then biologics (PsoBest registry data, 4/2018).

The advent of more effective treatments has led to a change in patients’ and physicians’ expectations of treatment outcomes. As a result, drug developers are now bound by more stringent measures of efficacy than in the past, with corresponding updates to treatment guidelines. For patients with severe psoriasis, treatment goals in 2004 were for a 50% improvement in Psoriasis Area Severity Index (PASI) 50.10 The introduction of TNF inhibitors opened up the potential for PASI 75 as a realistic treatment target for patients with severe disease.8,9 More recently, development of anti-interleukin (IL)-17 agents has changed the field of expectation for severe psoriasis once again, with PASI 90 achieved by >70% of patients and PASI 100 achieved by more than one-third of patients.11,12 The better response rates observed in these clinical trials could translate to revisions of treatment guidelines to include >90% improvement in PASI score as a realistic treatment goal for patients with severe psoriasis.

The most important issues for patients, in terms of treatment outcomes, are fast and sustainable improvements in skin symptoms without the fear of a subsequent relapse.4 As discussed, systemic and biologic medicines have transformed the treatment landscape for patients with severe disease, while patients with mild psoriasis often have excellent responses to topical treatments or phototherapy. However, patients with moderate disease often fall somewhere in between, with symptoms that are too severe to respond to topical treatment or phototherapy but too mild to be treated with systemic agents. In these cases, treatment choice may be guided by the presence of comorbidities.

Approximately 30% of patients presenting with psoriasis develop psoriatic arthritis.13 For a patient with moderate skin symptoms displaying evidence of arthritis, it is essential to initiate early intervention with systemic treatments to prevent radiographic progression of arthritis, which can result in irreversible joint damage.13 Treatment goals for patients with psoriatic arthritis are focussed on improvements in tender and swollen joints and enthesitis, alongside improvements in skin symptoms (PASI score and body surface area) and quality of life.14 Conventional TNF inhibitor treatments only achieve <60% response rates for American College of Rheumatology (ACR) 20% improvement criteria (ACR20) in patients with psoriatic arthritis, leaving much room for improvement.15-18 More recently, phosphodiesterase-4 and IL-17 inhibitors have shown more promising results.19 Recent guideline updates differentiate psoriatic arthritis from psoriasis for the selection of biologic treatments.20,21 Future guideline updates must consider optimal treatments for disease severity and comorbidities, as well as patients’ expectations for treatment outcomes.

Understanding Disease Processes

A broader understanding and better treatment of systemic inflammation are improving outcomes for a wide range of diseases with an inflammatory component, including psoriasis.22,23 For example, the presence of low-grade systemic inflammation in psoriasis, involving a variety of cytokines, may explain why phototherapy focussed solely on the skin is not effective in some cases. In addition, low-grade chronic systemic inflammation is thought to be responsible for a range of diseases, including nonalcoholic fatty liver disease, psoriasis, and cardiovascular disease.24 Thus, while patients with psoriasis have an increased risk of developing cardiovascular disease, adequate treatment and disease control can reduce this risk, a finding which has led to psoriasis being used as a model to explain inflammatory artherogenesis.25 Similarly, research into psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis has identified the fundamental similarity of these diseases at the molecular level. Variation in the levels and location of expression of cytokines in the IL-17/IL-23 pathway is associated with a wide range of pathological processes, including enthesitis and bone formation, differentiation of osteoclasts (leading to bone erosion), proliferation of fibroblasts (leading to matrix destruction), and proliferation of keratinocytes (leading to skin inflammation and plaque formation).26 Data from patients enrolled in psoriasis registries have also shown improvements in other comorbidities, such as depression, following systemic treatment for skin symptoms.27

Systemic Psoriasis Treatments: Fumaric Acid Esters and Dimethylfumarate

While much attention is given to new biologic treatments, advances in other systemic therapies have also improved treatment options and outcomes for patients with psoriasis. FAE have been used to treat psoriasis for almost 60 years,28 and they also have diverse applications beyond psoriasis, both within biomedicine and even in the food, agriculture, and green chemistry industries.29 Historically, it was thought that psoriasis was caused by a fumaric acid deficiency that could be cured by conversion of FAE to fumaric acid in the body. While FAE are indeed converted to fumaric acid, it is now known that fumaric acid deficiency is not the cause of psoriasis but that multiple inflammatory pathways are responsible.5,6

All FAE treatments contain DMF as the main active component.30,31 When administered orally, as with most psoriasis treatments, DMF is primarily metabolised via the citric acid cycle and eliminated as CO2 during exhalation.30 One of the stages of this process, occurring following absorption from the gut, is the partial conversion to monomethylfumarate (MMF), which, unlike DMF, can be detected in the circulating blood. It is believed that DMF and MMF act at different body sites, including the mucosa, skin, and the central nervous system.30 Although further research is needed to uncover the full effects of DMF and MMF, they are known to have multimodal activity, influencing multiple cytokine and lymphocyte pathways, including glutathione modulation and signalling via nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor (Nrf2), nuclear factor kappa B (NFκB), and the Janus kinase/signal transducers and activators of transcription (JAK/STAT) pathway.30,32-34 This activity results in broader effects in the body beyond skin symptoms; FAE have been shown to affect endothelial and cardiovascular functions,35-37 restore apoptosis sensitivity, and reduce melanoma growth rate and progression to metastases.38,39

Since their introduction in the 1950s, FAE have been and remain widely prescribed.40,41 In psoriasis, FAE act relatively slowly but week-by-week improvements in skin symptoms are usually noted. Combining FAE with topical treatment or phototherapy can result in more rapid improvements and allow for dose reduction compared to FAE treatment alone.42,43 The speakers highlighted that FAE are a suitable treatment option for a large proportion of patients since they tend to have similar efficacy regardless of the location of psoriasis; notable exceptions are nail psoriasis or psoriatic arthritis, which do not respond as well to FAE treatment. German treatment guidelines indicate FAE as a first-line systemic treatment prior to biologic therapies for all but the most severe psoriasis cases, and for those with evidence of arthritis.20 A discussion of dosing strategies indicated that while there is no severity threshold for treatment with FAE and dosing strategies can be flexible to meet patient needs, faster-acting treatments should be considered for patients with severe disease. When it is appropriate to use FAE, dosing usually starts low, increasing gradually until a response is achieved or adverse events trigger a dose reduction. Treatment can then continue providing it remains safe and effective, and dosing can be gradually increased, decreased, or stopped and restarted according to response. Following a response, the dosage can be reduced every 4 weeks by reducing the number of tablets taken daily by one.

The importance of discussing potential side effects with patients when considering FAE therapy was also raised, since this represents the best route to ensuring that patients adhere to treatment. Gastrointestinal complaints and flushing can be common and of particular concern to patients; however, they are often temporary and mild in severity. Patients who develop side effects might temporarily reduce their daily dose. If this approach is unsuccessful, it may be necessary to discontinue treatment.

Lymphopenia is a particularly important adverse event associated with FAE treatment, since prolonged lymphocytopenia is associated with the development of progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy, a rare adverse event.44 Identification of lymphopenia and careful monitoring and management is important to minimise the risk of developing progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy.45

Lessons from Real-World Registry Data

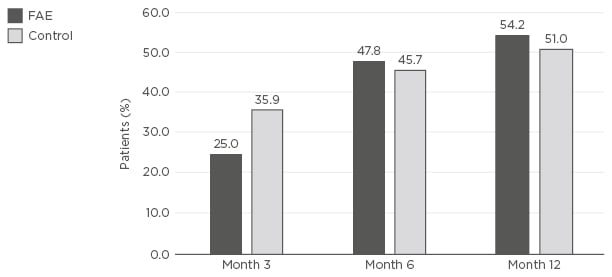

Efficacy, safety, and treatment patterns with FAE therapies have also been assessed in real-world studies, including patient registries. The German PsoBest Registry includes 7,600 patients with psoriasis under the care of >850 dermatologists.46 The registry employs robust methods, with the researchers analysing treatment patterns, efficacy, and safety for patients every 3 months from the first systemic treatment dose.46 A total of 10 years of follow- up data are now available for the first patients enrolled. Analyses of the data have suggested that patients treated with FAE have a greater need for improvement in skin symptoms and lesser need for improvement in pain than patients receiving biologics or alternative systemic therapies.47 This could be explained by the lower prevalence of arthritis among these patients. Efficacy comparisons with other agents based on achieving PASI 75 have suggested that although they have slower onset of efficacy, FAE have similar or greater efficacy compared with nonbiologic systemic therapies, the most common of which being methotrexate, over the longer term (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Proportion of patients achieving Psoriasis Area Index Severity 75 at Month 3, 6, and 12 after enrolment to the PsoBest registry and treatment with the first systemic agent.

A comparison was made between FAE and other nonbiologic systemic agents (control). The control group represents all available systemics prescribed to enrolled patients, most commonly methotrexate (PsoBest registry data, 4/2018).

FAE: fumaric acid esters.

Safety analyses using PsoBest data indicated that FAE were associated with higher rates of skin reactions (erythema and flushing), lymphopenia, and gastrointestinal disorders (e.g., cramps, diarrhoea), and lower rates of infections and infestations, when compared with other nonbiologic systemic therapies (PsoBest registry data, 4/2018). However, these adverse events were generally considered to be manageable and there were no significant differences in serious events in any system organ class between FAE and other systemic therapies.48 Similar event profiles were reported for FAE and DMF during the Bridge study,49 although this study compared both FAE and DMF with placebo, rather than with other nonbiologic systemic drugs. Drug survival for FAE is good, with 60% of patients remaining on treatment after 2 years. This is comparable to the drug survival observed with other nonbiologic systemic agents but is lower than the drug survival levels observed with the biologic agents adalimumab and ustekinumab. (PsoBest registry data, 4/2018).

The Effects of Drug–Drug Interactions and Coexisting Medical Conditions in Treating Psoriasis

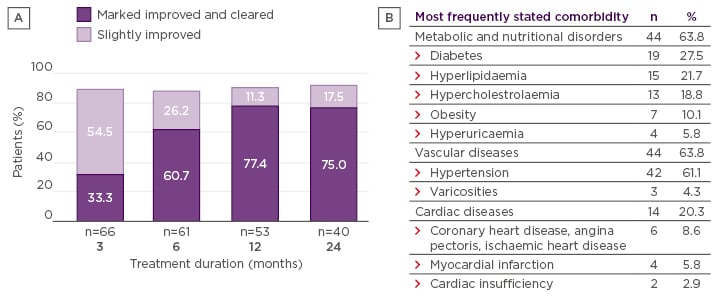

The underlying systemic inflammation associated with psoriasis means that patients are likely to present with at least one medical condition for which they are receiving other medications. The most common comorbidities include metabolic and nutrition disorders (e.g., diabetes and hyperlipidaemia) and cardiac disease.50 Due to this, drug–drug interactions are an important consideration when determining optimal treatment for psoriasis, and methotrexate, for example, is known to interact with other drugs.51 FAE are not metabolised via common pathways, e.g., via cytochrome 450, and coadministration with medications used to treat the most common comorbidities does not appear to have a large impact on their efficacy (Figure 3).41,50 In addition, patients receiving FAE are able to mount an effective immune response to vaccinations during therapy.52 Reported changes in laboratory parameters are often insignificant, rarely requiring dose modification of FAE.50 However, patients with psoriasis should be screened for medical conditions, including pregnancy, prior to starting medication to ensure they are receiving the optimum treatment strategy.

Figure 3: A) Improvement in skin symptoms among patients comedicated with fumaric acid esters and agents to treat comorbidities, according to the Physician’s Global Assessment. In the FUTURE study, 67% of patients at 6 months and 78% at 24 months who received FAE had a response of markedly improved or clear (21% of patients comedicated);41 B) The most common comorbidities in the FACTS study.

Adapted from Thaçi et al.50

Future Perspectives

While the active component of FAE treatment is DMF, many agents include additional FAE in combination with DMF. Recent research has focussed on isolating DMF for use as a monotherapy and clinical trials have demonstrated similar efficacy and safety of FAE combination and DMF monotherapy,49 as well as no negative effects on immunisation or seroprotection.52 In June 2017, Skilarence® (Almirall, Barcelona, Spain), a DMF monotherapy, became the first FAE to be licensed by the European Medicines Agency (EMA) for the treatment of moderate-to-severe plaque psoriasis in adults in need of systemic medicinal therapy.53,54 Prior to this approval, Fumaderm® (Biogen Idec GmbH, Ismaning, Germany), a combination of four FAE, was the only FAE treatment approved in Europe; however, Fumaderm was only licensed for use as a psoriasis treatment in Germany. DMF monotherapy has been available in Germany since October 2017, during which time data from the PsoBest registry have shown that most patients receiving Fumaderm have since been switched to receive DMF monotherapy (PsoBest registry data, 4/2018).

Many new biologic treatments have recently been approved for the treatment of psoriasis and/or psoriatic arthritis, and several more are in development. To date, biologic medicine development has focussed on the IL-17/IL-23 pathway, for which promising results have been shown in both diseases.11,12 Future research is likely to focus on maintenance of remission after treatment withdrawal. Recent trial data suggest that long-term remission (PASI 75 and PASI 90) could be possible following anti-IL-23 treatment, even when treatment is stopped.55,56 Future improvements in treatment availability and selection will rely on the identification and monitoring of biomarkers, leading towards personalised medicine and precision healthcare, ensuring patients’ individual needs are met.

Conclusion

Understanding of the complexities of psoriasis has greatly improved over the past 20 years, coinciding with improvements in disease control and management. The advent of systemic and biologic therapies has revolutionised treatment for patients but has also led to higher expectations for treatment outcomes. The drug development pipeline for psoriasis is very promising and dermatologists should expect ongoing changes to treatment guidelines in response to future drug approvals. Since their introduction >50 years ago, FAE have become a valuable and cost-effective systemic treatment choice for moderate-to-severe psoriasis. FAE are suitable for the short and long-term treatment of patients receiving comedication, provided that the dose is individually tailored to the patient’s needs regarding severity of disease and comorbidities. As such, FAE are now recommended as a first-line treatment option in new German treatment guidelines.20 Recent advances have led to the European approval of Skilarence, a DMF with similar efficacy and safety to FAE, which has increased patient access to this important treatment. Future developments in psoriasis treatment will focus on long-term maintenance of response and identification of biomarkers for a personalised approach to treatment.