Meeting Summary

This symposium explored the challenges of plaque psoriasis that are more prevalent in, or specific to, women, in terms of burden, treatment needs, and treatment options. This theme was introduced by Prof Augustin who described the social and emotional burden of plaque psoriasis and gender differences in relation to its impact and treatment expectations. Many areas, such as relationships, sexual activity, childbearing, and educational and career prospects can be affected in women, and as well as possible disease progression, need to be considered when discussing therapeutic options with the patient. Dr Egeberg outlined the certolizumab pegol (CZP) plaque psoriasis clinical trial programme. Three-year treatment results from the CIMPASI 1 and 2, and CIMPACT Phase III trials, showed that the clinical responses previously reported for moderate-to-severe plaque psoriasis with CZP 200 mg every other week (Q2W) or 400 mg Q2W for up to 48 weeks were well maintained over 3 years, with no new safety signals observed, underpinning the durability of the efficacy profile of CZP. Aligned with the unique Fc-free structure of CZP, clinical findings of no-to-minimal transfer of CZP from mother to infant or into breast milk, mean that CZP could be used during pregnancy if clinically needed and post-partum. Dr McBride described the profound life-impact of plaque psoriasis specifically in women and why it is essential to understand their needs and life goals when exploring treatment options. She discussed the importance of reviewing family planning and conception plans at every visit in case of changes in treatment needs. Immediate and future life plans, including the impact of pregnancy, childbirth, and the postpartum period, need to be considered when exploring treatment options with the patient. Women with plaque psoriasis face significant challenges and there is a need for long-term, effective treatments that are compatible with pregnancy and breastfeeding.

Introduction

Professor Matthias Augustin

The objectives of this symposium were to understand the importance of planning treatment addressing the specific needs of women living with moderate-to-severe plaque psoriasis throughout their life journey, and to discuss the importance of shared decision making early in the management of plaque psoriasis in women, as well as to identify any particular issues or helpful tools that could aid this decision-making process. A further objective was to share data on the durable efficacy of the TNF inhibitor CZP and its consideration for treating plaque psoriasis in women.

Meeting the Expectations of Patients Living with Plaque Psoriasis

Professor Matthias Augustin

The emotional and social burden of plaque psoriasis is considerable. One in four patients believe that their psoriasis makes it harder to find work and has stopped them following their chosen career.1 Approximately one-fifth of patients are affected by depression, with suicidal ideation reported for between 2.5% and 9.7%.2-5 Most patients reported feeling stigmatised and isolated and many fear passing on their psoriasis.6 Patients with plaque psoriasis are also more likely than the general population to be affected by other chronic and serious diseases including psoriatic arthropathy, anxiety and depression, metabolic syndrome, cardiovascular disease, and inflammatory bowel disease.2,3,7-13 Quality of life across a range of emotional and physical components is negatively affected, with 94% of psoriasis and psoriatic arthropathy patients reporting that their condition was a problem in daily life, 88% that it affected their emotional wellbeing, and 82% that it interfered with their enjoyment of life (n=5,604 patients).14 The emotional impact also increases with disease severity,14 and mental illness, including disorders due to substance abuse, mood and stress-related disorders, is also more frequent in patients with plaque psoriasis.15 In one survey of the burden of skin manifestations of plaque psoriasis, patients (n=17,434) reported negative effects on a number of aspects of their lives including sleep, working life, and sexual activity; in another, 79% of the respondents (n=40,350) reported that their daily life was disrupted for 10% of the time.16

Psoriatic lesions in the abdominal, genital, buttock, and lumbar areas have been associated with an increased likelihood of sexual dysfunction, independent of anxiety or depression.17 Patients with genital lesions had higher Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI) scores (mean 8.5 versus 5.5 without; n=487).18,19 Genital lesions are experienced by >60% of patients at some time,18 significantly impacting quality of life across a range of areas, including symptoms and feelings, personal relations, sexual difficulties, daily activities, and leisure.18,19

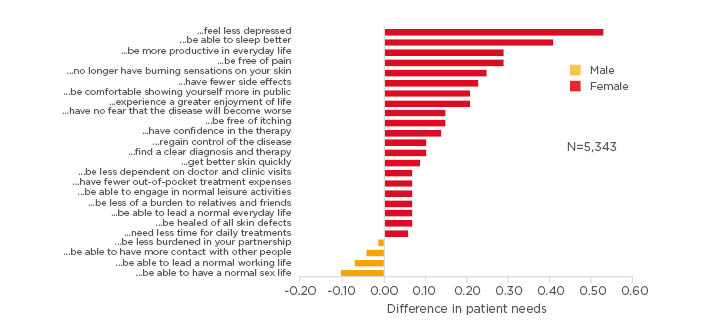

The emotional and social burden is clearly apparent when looking at patients’ treatment expectations beyond skin clearance and control, with gender differences in the burden experienced also reflected in these expectations. Women express a greater need to be free of pain and discomfort and to feel more in control of their disease and treatment, particularly with respect to emotional and social wellbeing (Figure 1).20 Furthermore, in a Swedish Registry study (n=2,450), although more men than women had Psoriasis Area and Severity Index (PASI) 75 scores >10 (35% versus 27%), more women had DLQI scores >10 (38% versus 28%).21 In this same registry, only one-third of patients receiving treatment with a biologic agent (n=589) were women, in spite of the higher impact on quality of life.21

Figure 1: Differences in patients’ plaque psoriasis treatment needs by gender.

Patients were recruited from the German and Swiss psoriasis registries PsoBest (n=4,894) and Swiss Dermatology Network of Targeted Therapies (SDNTT) (n=499).

Adapted from Maul et al 2019.20

Looking further at what drives gender-specific psoriasis experiences and treatment expectations, the 2017 World Psoriasis Happiness Report (n=121,800) found that women with plaque psoriasis experience a greater happiness gap from the general population than affected men, and were more likely to experience stress (>60% versus 42%) and loneliness than men (25–28% and 19–24%, respectively).22 Women experience greater stigmatisation because of their psoriasis than men, reporting significantly greater anticipation of rejection, feelings of being flawed, sensitivity to others’ opinions, and secretiveness.23 Women also reported a greater degree of suffering associated with genital lesions than affected men, including itch, pain, stinging, burning, and dyspareunia, as well as less frequent sex as a result of the lesions.18

Hormonal fluctuations during a woman’s lifetime can affect disease activity.24 A study of >150,000 women with plaque psoriasis illustrated clearly the various ways in which the disease can affect their life and disease journeys,25 with irregular versus regular menstrual cycles and a surgical menopause rather than a natural menopause being more likely in women with plaque psoriasis; whereas, women without plaque psoriasis were likely to breastfeed their infants for longer and showed a nonsignificant trend towards a higher likelihood of multiple births.25 While it is often stated that plaque psoriasis improves with pregnancy, in a prospective study of pregnant women (n=47), 44% had no change or worsening, and, strikingly, postpartum, 65% experienced worsening.26

In summary, there are gender differences in how patients experience plaque psoriasis. Female patients have different expectations and needs from therapy compared with men. Many areas, such as relationships, sexual activity, childbearing, and educational and career prospects,27-31 can be impacted by the disease or can cause worsening. These need to be considered when discussing therapeutic options with the patient.

Achieving Long-term Impact in Patients Living with Plaque Psoriasis with Certolizumab Pegol

Doctor Alexander Egeberg

The TNF inhibitor CZP differs in molecular structure from other antibody-based anti-TNF and anti-IL biologic therapies, as it is a PEGylated humanised anti-TNF Fab’ fragment without an Fc region.32-35

The Certolizumab Pegol Plaque Psoriasis Clinical Development Programme

A Phase III efficacy and safety programme in patients with moderate-to-severe plaque psoriasis was conducted across 11 countries in North America, western Europe, and eastern Europe. The three randomised, double-blind, parallel group Phase III trials (CIMPASI 1, CIMPASI 2, and CIMPACT) included >1,000 patients and comprised blinded, maintenance, and open-label periods.36-39 A Phase III study has also been completed in Japan.40

In CIMPACT, patients were randomised to either CZP 400 mg Q2W; CZP 200 mg Q2W, preceded by a CZP 400 mg loading dose at Weeks 0-2-4; etanercept (50 mg twice-weekly); or placebo. The primary endpoint was a 75% reduction in PASI 75 at Week 16. This was followed by a maintenance period up to Week 48, and then open-label treatment with possible dose adjustment (see CIMPASI-1 and 2) up to Week 144 .38,39 From Week 16, patients who had responded with a PASI reduction ≥75% were rerandomised to CZP 200 or 400 mg to explore dose optimisation. Patients with a PASI reduction <75% in all treatment groups received ‘escape’ treatment with CZP 400 mg Q2W.38,39

In CIMPASI 1 and 2, patients were randomised to CZP 400 mg, CZP 200 mg preceded by 400 mg loading dose at Weeks 0-2-4 or placebo (all Q2W). The primary endpoint was PASI 75 or a Physician’s Global Assessment (PGA) score of 0 or 1 at Week 16.37 From Week 16, patients who had responded on placebo with a PASI reduction ≥50–75% were re-randomised to CZP 200 mg. Nonresponders (PASI reduction <50%) were switched to ‘escape’ treatment as above in all treatment groups. From Week 48, open-label CZP 200 mg Q2W was continued to Week 144, but with the option of the higher dose if PASI reduction was <50%. During the open-label phase, dose adjustment between 200 mg to 400 mg Q2W could occur, and escalation was either mandated if patient response was <PASI 50 or permitted at the clinician’s discretion if the response was between PASI 50 and 75. De-escalation was also permitted for a response >PASI 75.37,39

Across CIMPACT and CIMPASI 1 and 2 (n=850), patients had quite severe plaque psoriasis at baseline (PASI ~20; mean affected BSA ~25%) and 25–30% had previously been treated with another biologic. Demographic and baseline characteristics of the pooled patients were well-balanced between CZP treatment arms and placebo.41

What May We Expect of a Biologic in the Treatment of Plaque Psoriasis?

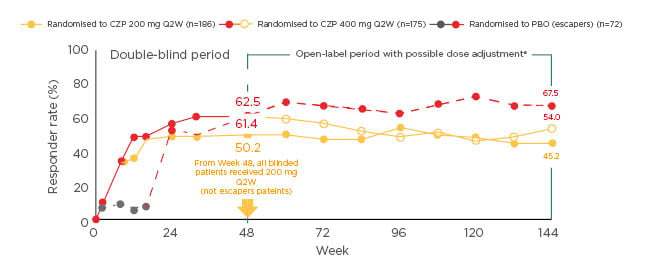

There were consistent clinical responses (PASI 75) in the Phase III trials after 16 weeks’ treatment with CZP 200 mg (<75%; n=351) or 400 mg (<80%; n=342) Q2W.37,38 In the long-term analysis of CIMPASI 1 and 2, the PASI 75 response rate was approximately 70% (n=186) after one year’s treatment with 200 mg Q2W, and the PASI 90 rate was approximately 50%. These rates remained stable over the remainder of the study up to Week 144, with most patients staying on 200 mg Q2W.39,42

With the 400 mg Q2W dose, >60% of patients had a PASI 90 response after 1 year (PASI 75 84%; n=175). When the dose was lowered to 200 mg Q2W, response rates decreased slightly, but stabilised at >70% for PASI 75 and >40% for PASI 90.39,42 For patients originally randomised to placebo, but who crossed over to 400 mg Q2W, PASI 75 at 1 year was 83% and PASI 90, 60% (n=72). Most patients (63%) then continued on the 400 mg dose, but the remainder switched to the lower dose; similarly, response rates remained stable over the remainder of the study.39 These findings show that dose adjustment could be practical in real-life clinical practice. Evaluating quality of life impact, more than 50% of patients (n=361) treated with CZP had a DLQI of 0 or 1 after 1 year (>60% with 400 mg Q2W [hl]Figure 2[/hl]), demonstrating that they were effectively normalised with respect to DLQI.39 No new or unexpected safety signals were identified during long-term treatment when compared to previously reported data for CZP in psoriasis and in other indications as well as other TNFi agents approved for psoriasis. The most frequently reported adverse events were nasopharyngitis (IR 14.2) and upper respiratory Infections (IR 7.9) with an overall similar profile and discontinuation rate for both doses. There was no sign of an increased risk of infections with continued exposure over time.39

Figure 2: Percentages of patients with mild-to-moderate plaque psoriasis who had Dermatology Life Quality Index scores of 0 or 1 when treated with certolizumab pegol 400 mg every other week for up to 144 weeks.39

Markov Chain Monte Carlo imputation. Missing values were imputed based on all data available for a given patient. This was repeated several times, and logistic regression applied to generate a single estimated responder rate for each visit. Results for the escape arm patients and the certolizumab pegol-randomised patients originate from two independent models.

aDose adjustments were mandatory in patients with Psoriasis Area and Severity Index (PASI) <50 and at the investigator’s discretion in patients with PASI 50–74. Patients who received 12 weeks certolizumab pegol 400 mg every other week could dose-reduce at the investigator’s discretion if they achieved PASI 75 and were withdrawn if they did not achieve PASI 50. PASI 75/90: ≥75/90% improvement from baseline in PASI.

CZP: certolizumab pegol; PBO: placebo; Q2W: every other week.

Other Elements to Consider in Clinical Practice

There are several reasons why patients with plaque psoriasis may switch between biologics, including life events and lack of response to treatment. In patients who were responsive to etanercept (n=74), responsiveness was maintained after switching to CZP (200 mg Q2W), with an increase in PASI 90 from 30% to 78%.43 Nonresponsive patients who were switched to CZP (400 mg Q2W), had improvements in PASI 75, PASI 90, and PGA 0/1.44 In psoriatic arthritis patients with plaque psoriasis (BSA ≥3%) treated with CZP, improvements in PASI 75 scores and complete resolution of nail disease were sustained over 216 weeks.45 Patients treated with CZP also showed stable response rates across a range of BMI subgroups.46

The expectation that the unique Fc-free structure of CZP prevents its active placental transfer32-35 aligns with pharmacokinetic findings of no-to-minimal (<0.1%) transfer from mother to infant;47 similarly, there was minimal transfer of CZP in breast milk.48 Unlike several other biologic agents, CZP treatment can therefore be considered during pregnancy if clinically needed and in breastfeeding mothers.49

In summary, CZP showed durable efficacy over 3 years in plaque psoriasis. Responder rates were higher with 400 mg Q2W and gradually decreased with dose reduction to 200 mg Q2W, suggesting that continued treatment at 400 mg Q2W may be needed to maintain optimal response. No new or unexpected safety signals were revealed in the long-term study. There was also no-to-minimal placental transfer of CZP from mother to infant or into breast milk.

Unique Patient Challenges and How to Address Them

Doctor Sandy McBride

The everyday reality for many women with plaque psoriasis is very far from the aspirational images of female beauty promoted in the media. In a study in which women with severe plaque psoriasis wrote postcards to express their feelings towards their disease, many expressed feelings of distress, such as feeling separated from other women and alone because of their psoriasis, as well as low self-esteem and self-denigration.50 Women have also been reported to experience higher stigmatisation than men because of their psoriasis.23

When analysed by gender, World Psoriasis Happiness Surveys data for >50,000 women and >35,000 men with plaque psoriasis, showed that affected women had lower life satisfaction than affected men and the general population. They were also more likely to experience feelings of loneliness and higher levels of stress, with differences greatest in younger women.51 For women with plaque psoriasis, anxiety and depression can be an everyday occurrence throughout their lifetime.50

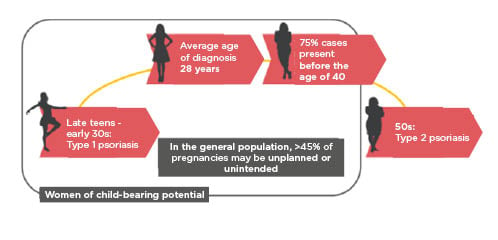

Women usually develop Type 1 psoriasis when they are at the age of child-bearing potential, generally from their late teens to early 30s, with 75% of cases presenting before age 40 years (Figure 3).52,53 It is an everyday reality of clinical practice that almost half of pregnancies are unplanned or are unintended,54 which presents a considerable challenge when treating plaque psoriasis in women of childbearing age. Questions to the symposium audience showed that while most participants asked their patients about family planning before initiating treatment, this was rarely asked about again after treatment initiation. Furthermore, although family planning partnership with their dermatologist is critical to successful outcomes,22 in a USA study of 141 women with plaque psoriasis, 88% sought advice from the internet, 7% reported that their dermatologist initiated family planning discussions, and 21% did not even inform their dermatologist they were pregnant.55 A snapshot clinic audit found that family planning was discussed with 62.5% of patients before treatment, but with only 12.5% at subsequent visits (Dr McBride and colleagues, through personal communication). These findings led to the introduction in the clinic of a brief questionnaire for completion by female and male patients at every clinic visit on pregnancy, fathering a child, and contraception use, so that patients’ needs could be reviewed and addressed if they had changed (Dr McBride and colleagues, through personal communication).

Figure 3: Plaque psoriasis: A woman’s journey.

Onset and diagnosis frequently occur when women are of child-bearing age. The patient’s wishes to plan for a family and also the high risk of unintended pregnancy therefore need to be considered when planning treatment.52–54,56

Plaque psoriasis impacts pregnancy and its outcomes. Women <35 years of age with plaque psoriasis (n=7,400) have a 22% lower likelihood of pregnancy than the general population,56 with those with moderate-to-severe plaque psoriasis having ≤50% fewer children.57 The risk of complications such as gestational hypertension and diabetes, pre-eclampsia, and the need for caesarean section are increased in moderate-to-severe plaque psoriasis, which has also been linked to increased likelihoods of preterm birth and low birth weight.58 Women with psoriatic disease may suffer Koebnerization at their nipples from infant suckling and may therefore be less likely to breastfeed.59 Dr McBride also referred to findings that almost half of women with plaque psoriasis reported no change or worsening during pregnancy, and post-partum, two-thirds experienced worsening.26 It is therefore important that women are followed up closely after giving birth. Dr McBride suggested that a lack of treatment options during pregnancy and breastfeeding leads to treatment being stopped during pregnancy, which may result in disease flares and effects on psychological wellbeing. For example, the prevalence of depression in women with plaque psoriasis is doubled during pregnancy.60,61 Treatment and support for women with plaque psoriasis during and after pregnancy therefore needs to improve. In summary, plaque psoriasis has a profound life-impact in women. Women with plaque psoriasis face unique challenges and there is a need for long-term, effective treatments that are compatible with pregnancy and breastfeeding.

AUDIENCE QUESTION AND ANSWER SESSION

The panel were asked if they treat men and women with plaque psoriasis differently. Dr McBride replied that in their clinic they now ask their patients about their plans for conception and pregnancy at every visit. When biologic therapies are discussed with women, their long-term treatment journey and pregnancy plans should be considered. Dr Egeberg commented that this should be the case as men and women with plaque psoriasis have differing expectations of treatment and are affected differently by the condition; additionally, some treatments such as acitretin should not be used in fertile women. It was also asked if male and female dermatologists treat their patients differently. Dr McBride suggested that from personal experience she might have a better understanding of pregnancy and breastfeeding, and therefore post-partum treatment needs, than a male colleague, and also might be more likely to consider the likelihood of pregnancy during treatment. Dr Egeberg concurred, commenting that everyone has their own reference points, for example, a male dermatologist may not fully appreciate how risk averse pregnant women might be when thinking about treatment. Prof Augustin added that it is important that male and female colleagues learn from each other.

Dr McBride was asked about the implementation of the family planning and pregnancy questionnaire in clinical practice and if these have been helpful. She explained that these questionnaires are given to all patients for completion and review before the patient is seen by the dermatologist. They have been found to be very helpful. The panel also noted the value of telephone clinics as an aid to extending the intervals between clinic visits.

It was asked if DLQI was useful in clinical practice. Dr Egeberg described how, in their practice, a system of colour coding patient records by DLQI score was used to track changes in wellbeing and helped dermatologists focus on managing specific issues before they arise or worsen. Asked about stopping and restarting CZP treatment, Dr Egeberg commented that in his opinion he would prefer that CZP was not stopped during pregnancy if clinically needed; however, if it is stopped, it would be the patient’s decision to restart. He added that after a long pause in treatment, it may be difficult to regain control of symptoms. The panel agreed that there was a need to ensure that the obstetrics and gynaecology team caring for the patient during pregnancy are aware of their psoriasis and CZP treatment.

It was asked if unconscious gender bias and inequality affected the treatment of plaque psoriasis in women. Dr McBride replied that she wished that both women and men with plaque psoriasis were more able to talk to others about their condition. Dr Egeberg added that dermatologists needed opportunities for reflection and supervision on how gender might impact their practice. It was asked if the CZP clinical trial and registry data have been analysed by gender. Dr Egeberg replied that the 3-year data have not yet been analysed, but registry data are being evaluated. After the meeting, it was noted that analysis of pooled 16-Week Phase III data found no significant difference in efficacy between male and female patients.62

CONCLUSION

It is essential to understand the needs and life goals of women with plaque psoriasis, and clinicians should ask them how they think their lives would be different without the condition. Treatment should be chosen with the patient after considering both their immediate and future needs. Family planning and conception plans need to be reviewed at every visit to ensure that current treatment is aligned with the patients’ life plans. The long-term clinical data for CZP in plaque psoriasis showed a durable efficacy following dose adjustment, which will aid effective treatment in real-world clinical practice. All biologics are, however, not the same, and CZP has particular characteristics and promising clinical data that physicians may wish to consider early in the treatment journey of their female patients. Women’s and men’s requirements and expectations from treatment differ in many areas and clinicians need to be aware of the specific and changing needs of women with plaque psoriasis throughout their life.