Abstract

Extramammary Paget disease (EMPD) is a rare, cutaneous condition, which can present secondary to underlying carcinoma as an eczematoid rash that often mimics other conditions. Secondary EMPD should, therefore, be considered in the differential diagnosis where there is potential for malignant extension, particularly in post-operative tissue. This report describes a case of secondary EMPD of the peristomal skin in a patient with a distant history of cystectomy with ileal conduit for urothelial carcinoma, who developed an extensive eczematoid rash over 5 years after attempting several ineffective treatments. Early dermatologic referral for persistent inflammatory cutaneous disorders and appropriate histopathologic testing may reduce delays in the diagnosis of EMPD.

INTRODUCTION

Extramammary Paget disease (EMPD) is a relatively rare condition, with a reported incidence of 0.1–2.4 patients per 1,000,000 person years.1 It most commonly presents in the vulvar region of White females between 50 and 80 years of age.1 EMPD clinically presents as an erythematous eczematoid rash that clinically mimics inflammatory cutaneous disorders, which may result in a delayed diagnosis.2 EMPD can be classified into primary and secondary, with the latter representing the spread of non-cutaneous internal carcinoma by direct extension or by epidermotropic metastasis. The most common carcinomas that cause secondary EMPD are anorectal and urothelial carcinomas.2 Here, a case of secondary EMPD of the peristomal skin is reported in a patient with a distant history of cystectomy with ileal conduit for urothelial carcinoma, who developed extensive peristomal eczematoid rash over 5 years.

CASE DESCRIPTION

An 87-year-old male with a history of invasive transitional cell urothelial carcinoma of the bladder, left distal ureter status post-radical cystoprostatectomy, left distal uretectomy with ureteroureterostomy, and an ileal conduit urinary diversion 14 years prior, presented at the authors’ dermatology clinic with complaint of a peristomal rash that had persisted for many years. The patient reported that the rash had been present for at least 5 years and was getting larger and described it as pruritic and tender. The rash was initially attributed to urine leakage and had been treated as eczema and a fungal infection with wound and stoma care, as well as topical antifungals, unsuccessfully for years prior to presentation. The patient had been using wound cleanser spray, normal saline, nystatin powder, and miconazole. The dermatologic exam revealed a large erythematous plaque with areas of maceration around the stoma, involving most of the right abdomen extending to the pubis (Figure 1).

Figure 1: A peristomal, macerated, bright red plaque involving the right abdomen of the patient.

The stoma is seen in the central, lower portion of the image as an erythematous circular depression.

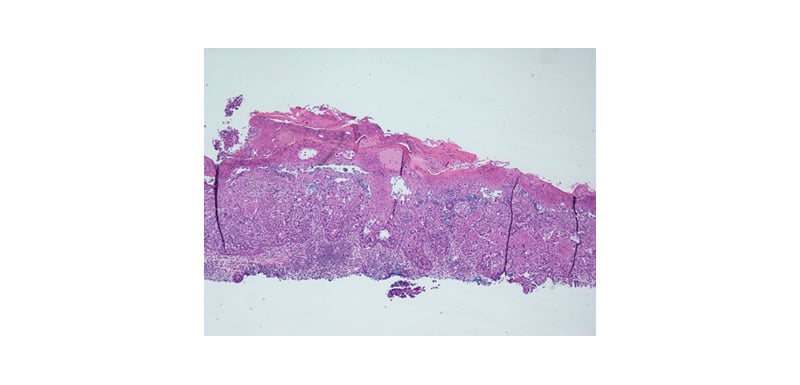

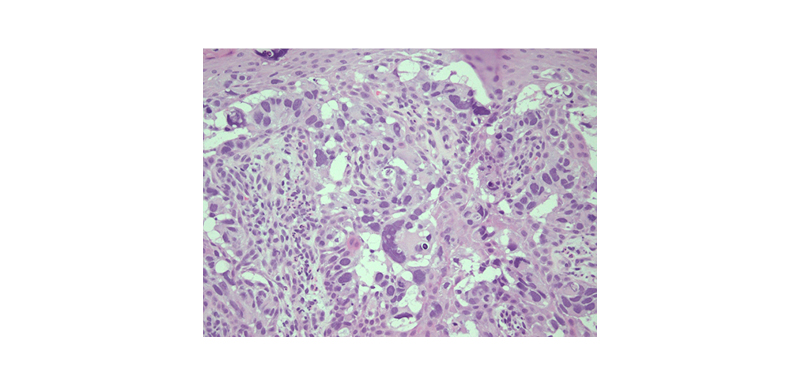

A shave biopsy was performed from around the peristomal lesion for histopathologic diagnosis. The biopsy showed infiltration of the epidermis, with large atypical epithelioid cells with enlarged hyperchromatic nuclei and pale cytoplasms in solitary units and nests (Figures 2 and 3). These cells showed diffuse and strong expression of cytokeratin 7 and GATA3, and focal expression of cytokeratin 20 (CK20), the CDX2 protein, and the BerEp4 antibody. The cells were negative for the proteins p63, carcinoembryonic antigen, Sox10, prostate-specific antigen, and thyroid transcription factor-1. No intracytoplasmic mucin was seen on the mucicarmine stain and a periodic acid–Schiff stain was negative for fungal organisms. The morphologic and immunohistochemical features are consistent with secondary EMPD, and consistent with the involvement of the patient’s known urothelial carcinoma of the bladder.

Figure 2: The epidermis displaying infiltration by large atypical epithelioid cells at low magnification (haematoxylin and eosin stain; original magnification: x40).

Figure 3: A high magnification (haematoxylin and eosin stain; original magnification: x400) view of lesion-displaying cells in solitary units and nests with enlarged hyperchromatic nuclei and pale cytoplasms.

These findings could represent local extension from recurrent cancer in the stoma itself, or metastasis. A biopsy of the stoma and urothelial tract, as well as CT scans of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis with and without contrast, were planned to assess for metastatic disease. However, soon after the diagnosis was made, the patient stated that they did not want to receive any invasive treatment or procedure and opted for do-not-resuscitate status. The patient was offered palliative therapy with topical imiquimod and radiotherapy, which they denied. This patient passed away years later from other systemic complications.

DISCUSSION

Currently, the exact mechanism underlying EMPD is unknown, but two widely known theories exist, namely the epidermotropic and transformation theories. The epidermotropic theory is more commonly accepted and suggests the migration of adenocarcinoma cells into the epidermis, while the transformation theory postulates the in situ malignant transformation of basal keratinocytes.3 However, there remains a lack of evidence for either theory and the pathogenesis of EMPD is considered controversial. There have been several studies that have sought to identify biomarkers and signalling pathways in an effort to guide the development of EMPD treatments. Specifically, the Musashi-1–mammalian target of rapamycin pathway has been cited as promoting the Paget cell conversion of keratinocytes, suggesting that the utility of rapamycin as a novel therapy would be effective in patients expressing this phenotype.3 Similarly, human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (and downstream molecules in the Ras–Raf–mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase and phosphoinositide 3-kinase–protein kinase B–mammalian target of rapamycin pathways have been identified as potential targets for treatment.4 Although the current understanding of EMPD is improving, more research is needed to determine the implication of these findings on treatment options for patients with EMPD.

EMPD largely affects body areas with a high concentration of apocrine glands, most commonly the genitals; EMPD has rarely been reported to occur in body areas that are less populated with apocrine glands such as the trunk and the cheeks.2 A literature review composed by the authors revealed one similar case of secondary EMPD around a cutaneous ureterostomy stoma after radical cystectomy in an 85-year-old male.5 This patient, presented by Kanda et al.,5 similarly developed refractory dermatitis around a stoma on the abdominal skin. The time after the radical cystectomy and cutaneous ureterostomy were performed to the development of cutaneous manifestations was 4 years in this patient, which represents a similar time frame to that of the case study outlined in this article. The patient’s cutaneous malignancy was cured by skin excision around the cutaneous stoma; however, they ultimately died of metastatic urothelial carcinoma.5 Other cases exist of EMPD secondary to urothelial carcinoma, although the cutaneous manifestations presented on the apocrine-rich genital skin in these cases.6,7

Many different modalities of treatment exist for EMPD, depending on the presence or absence of metastatic disease and the surgical candidacy of the patient. In patients with primary EMPD, treatment typically consists of surgery with wide-local excision or Mohs micrographic surgery combined with adjuvant or neoadjuvant imiquimod.8 In patients with secondary metastatic EMPD, such as the one presented here, systemic chemotherapy is typically used. However, the most effective regimen for metastatic disease has not yet been established; secondary EMPD is difficult to treat and is associated with poorer outcomes. Proposed chemotherapeutic regimens include utilising antimetabolites such as 5-fluorouracil, alkylating antineoplastics like cisplatin or carboplatin, and alkaloids, including paclitaxel or docetaxel.8 Due to the patient’s poor surgical candidacy and do-not-resuscitate status, they were offered topical imiquimod therapy for palliation only, which the patient denied.

The dermatologic exam of EMPD most commonly demonstrates a well-demarcated, erythematous plaque, with or without overlying secondary skin changes. Due to the variation in clinical appearance, the initial differential for EMPD may include many different infectious and non-infectious entities, including dermatophytosis, irritant or allergic contact dermatitis, and inverse psoriasis. Adding to the diagnostic difficulty is the fact that patients may be asymptomatic or present with non-specific symptoms such as pruritus, tenderness, and burning.1 Given its ability to mimic several inflammatory conditions, the diagnosis of EMPD is often delayed by many years. Early recognition of EMPD is paramount given its tendency to demonstrate multifocal and discontinuous subclinical extension. It is, therefore, recommended that all patients with pruritic eczematous lesions on areas of apocrine gland-bearing skin who fail to respond to standard topical treatment after 4–6 weeks receive a skin biopsy of the affected area for diagnosis.1,2

CONCLUSION

In summary, it is important for the urologist and stoma care team to consider secondary cutaneous involvement by malignancy, regardless of the time passed postoperatively. Dermatology referral should be considered for most dermatological conditions that fail to improve or resolve as expected despite treatment, and this is particularly true of treated cancer patients with persistent peristomal rashes.