INTRODUCTION

Coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG) is a treatment option offered to a growing population of octogenarians, considering the constant rise in life expectancy.1 The dark side of surgical myocardial revascularisation for octogenarians is the lack of information on follow-up and comparability of mid-term outcomes with younger patients,2 as well as the benefits of tertiary prevention (mid-term management of coronary artery disease after CABG).3 Hence, the purpose of this study is to evaluate the 10-year outcomes of octogenarian patients after isolated CABG included in an Italian nationwide prospective registry.4

METHODS

The PRIORITY project was designed to evaluate the long-term outcomes of two large prospective multicentre cohort studies on isolated CABG.5 Patients younger and older than 80 years were identified. The primary endpoints were all-cause mortality and the overall rate of major adverse cardiac and cerebrovascular events (MACCE) at 10 years. Secondary outcomes included the individual components of MACCE. Baseline differences between the study groups were balanced with propensity score matching and inverse probability of treatment weight (IPTW).6 Time to events was analysed using Cox regression and competing risk analysis.7

RESULTS

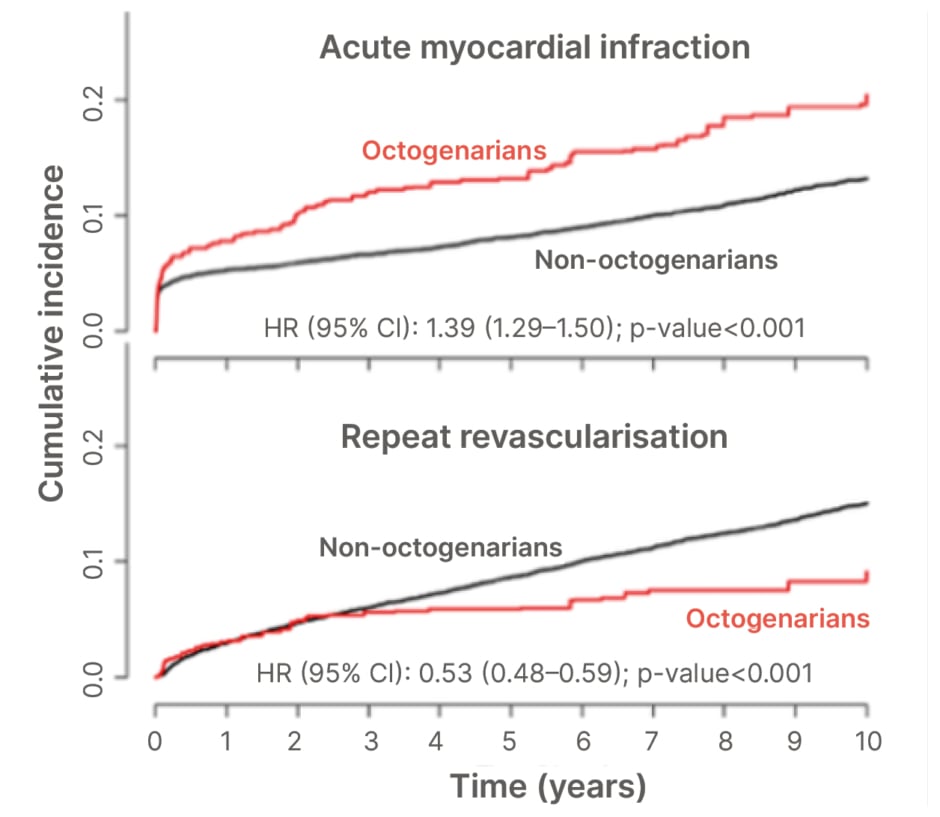

The cohort consisted of 10,989 patients who underwent isolated CABG with complete baseline clinical characteristics, operative data, and administrative follow-up. Of the patients, 872 (7.9%). The median follow-up time was 7.9 years. As expected, octogenarians showed poorer 10-year survival (hazard ratio [HR]: 3.09; 95% CI: 2.93–3.25; p<0.001) and MACCE (HR: 2.13; 95% CI: 2.04–2.22; p<0.001). Interestingly, although experiencing a higher cumulative incidence of myocardial infarction (MI) at 10 years (HR: 1.39; 95% CI: 1.29–1.50; p<0.001), octogenarians underwent a reduced incidence of 10-year myocardial revascularisation (HR: 0.53; 95% CI 0.48–0.59; p<0.001), corroborating the hypothesis of undertreatment for the elderly (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Inverse probability of treatment weight cumulative incidence of acute myocardial infarction and repeat revascularisation at 10 years.

HR: hazard ratio.

CONCLUSION

The main finding of this study was the opposite effect of advanced age on acute MI and repeat revascularisation. Indeed, apart from the expected worse survival and MACCE, the higher incidence of acute MI in octogenarians is not concordant with repeat revascularisation, which is significantly more represented in younger patients. It suggests a tendency for conservative approaches by managing the patient’s signs and symptoms with medical therapy alone.8 This result opens a debate on the choice of treating the elderly with CABG without guaranteeing clinical assistance comparable to younger patients.9 Clinicians should make meticulous considerations of the risks and benefits for each treatment option considering the personalised nature of cardiovascular medicine and surgery.