Abstract

Corticosteroids are one of the most effective medications available for a wide variety of inflammatory diseases, including rheumatoid arthritis, inflammatory bowel disease, autoimmune diseases, and chronic lung diseases such as asthma; however, 5–10% of asthma patients respond poorly to corticosteroids and require high doses, secondary immunosuppressants, such as calcineurin inhibitors and methotrexate, or disease-modifying biologics that can be toxic and/or expensive. Though steroid-resistant asthma affects a small percentage of patients, it consumes significant health resources and contributes to substantial morbidity and mortality. In addition, the side effects caused by excessive use of steroids dramatically impact patients’ quality of life. Recognition of patients who respond poorly to steroid therapy is important due to the persistent and considerable problems they face in managing their conditions, which bears a significant socioeconomic burden. Along with the recognition of such patients, elucidation of the molecular mechanisms of steroid resistance is equally important, so that administration of a high dosage of steroids, and the consequent adverse effects, can be avoided. This review provides an update on the mechanisms of steroid function and the possible new therapeutic modalities to treat steroid-resistant asthma.

INTRODUCTION

Glucocorticoids (GC), also called glucocorticosteroids or steroids, are the mainstay therapy for numerous inflammatory diseases, such as asthma, dermatitis, rheumatoid arthritis; prevention of graft rejection; and autoimmune diseases. GC are steroid hormones that are synthesised and released by the adrenal cortex. GC have profound effects on various cell processes and organ-specific biological functions.1 The regulation of downstream genes by GC involves either gene repression or activation. While gene activation leads to beneficiary actions of GC, repression of gene signalling is hypothesised to cause adverse effects due to prolonged use of steroids.2 Although the majority of patients with inflammatory diseases and immune disorders respond to oral GC, 10–20% of patients do not respond even to very high doses of GC. Resistance to steroids has also been reported in rheumatoid arthritis and inflammatory bowel disease and has been extensively studied in asthma. Despite the fact that only 5–10% of asthmatic patients do not respond to steroids, this leads to a significant socioeconomic burden and affects their quality of life as a result of the side effects associated with the prolonged usage of high doses of steroids.3 Therefore, it is important to identify the patients with poor responses to steroids and to elucidate the molecular mechanism of steroid resistance.

This review focusses on the features, possible resistance mechanisms known so far, and recent developments in the treatment regimen of steroid-resistant asthma. To understand steroid-resistant asthma, the authors also bring the normal function of the steroids in a cell to the attention of the readers.

THE DIVERSE PHENOTYPES OF ASTHMA

Asthma is characterised by reversible expiratory airflow obstruction or airway hyper-responsiveness and airway inflammation. Approximately 235 million people have asthma worldwide.4 In contrast to the previous Th2 dominant hypothesis, the phenotypes of asthma have been classified into high Th2 (eosinophilic inflammation) and low Th2 types (neutrophilic inflammation with Th1 and Th17 involvement).5,6 Asthmatics with high Th2 phenotypes are responsive to corticosteroids, whereas non-Th2 asthmatics are much less so. The current treatment includes increasing the dosage of corticosteroids or using secondary immunosuppressants that are more toxic. Biologics, such as monoclonal antibodies against proinflammatory cytokines like IL-4, IL-5, IL-13, and IgE, have also been tried.

CLINICAL PRESENTATION OF GLUCOCORTICOID-RESISTANT ASTHMA

The response to steroids can be visualised as a spectrum, with steroid resistance placed at one end. Complete resistance to steroids is a rare case; usually poor response to steroids is observed, so that a high dose of steroids is required to control asthma, a condition termed steroid-dependent asthma. In 1968, Schwartz et al.7 described GC resistance for the first time in six patients with low eosinopenic response, who did not respond clinically to high doses of systemic GC, although they showed reversibility to inhaled β-agonists. Later, a number of studies reported such insensitivity to steroids in asthmatic patients.3 The detailed analysis of these patients revealed that the unresponsiveness was due to the inefficiency in the anti-inflammatory effects of steroids rather than their metabolic or endocrine functions. The thickness of the airway epithelium and basement membrane in steroid-resistant patients was larger than the patients with steroid sensitivity, in spite of having similar epithelial damage.8 GC-resistant asthma is defined by a failure to improve forced expiratory volume in 1 second (FEV1) by >15% even after an adequate dose of prednisolone (40 mg) for 2 weeks. These patients present bronchodilation with inhaled β2 agonists and typical diurnal variation of peak expiratory flow.9 The diagnosis of steroid-resistant asthma is entirely based on the clinical history, symptoms, and lung function in the context of GC use. For a clear diagnosis, one has to rule out other diseases, such as cystic fibrosis and bronchiectasis.10 Currently, there is no available clinical marker or established immune adherence test for the diagnosis of steroid-resistant asthma.

To understand the mechanisms behind steroid resistance in asthma, one should first understand the functioning and the mechanism of steroid receptor action. This will enable the identification of more cues for the failure of its function, leading to steroid resistance.

THE GLUCOCORTICOID RECEPTOR AND ITS FUNCTION

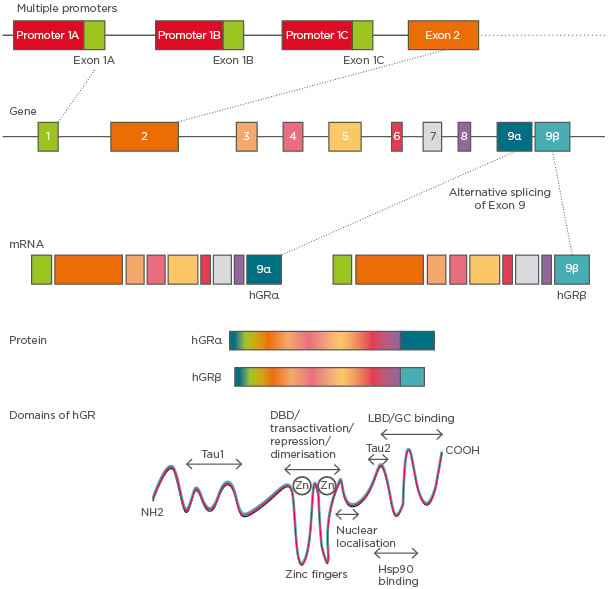

The GC receptors (GR) belong to the nuclear receptor Type I family. The human GR (hGR) gene is located on the chromosome 5q11-q13.11 The hGR gene consists of nine exons, wherein the protein coding region is present between exon 2 and exon 9 (Figure 1). hGR is known to have three alternative promoters: 1A, 1B, and 1C. Although hGR does not have prominent TATA or CCAAT boxes, it contains multiple GC boxes.12

Figure 1: hGR gene structure and its isoforms.

The hGR gene has nine exons and three variable promoters giving rise to several glucocorticoid receptor isoforms that differ in the 5’-untranslated region. Alternative splicing of exon 9 at the 5’ end gives rise to α and β isoforms. Domains of hGR show the LBD to be present at the C-terminal, which differentiates between hGRα and hGRβ in their functionality.

DBD: DNA binding domain; GC: glucocorticoid; hGR: human glucocorticoid receptor; Hsp90: heat shock protein 90; LBD: ligand binding domain.

Alternative splicing of GR pre-mRNA gives rise to two dominant isoforms: GRα and GRβ. GRα is located in the cytoplasm whereas GRβ remains in the nucleus and acts as a dominant negative or decoy receptor for GC13 (Figure 1). hGRβ was identified as having a potential contribution to GC resistance in several diseases. It has been shown that while proinflammatory cytokines such as TNF-α and IL-1 increase the expression of GRβ, the formation of the GRβ/α heterodimer attenuates the function of GRα14 (Figure 1). The GR protein has a modular structure similar to other members of its nuclear receptor family. It has three major domains: a) variable N-terminal domain (421 amino acids), b) central DNA binding domain (65 amino acids), and c) C-terminal domain (250 amino acids). Furthermore, the motif containing the nuclear localisation signals is present in both the DNA binding domain and ligand binding domain.15

Mechanism of Glucocorticoid Receptor Action

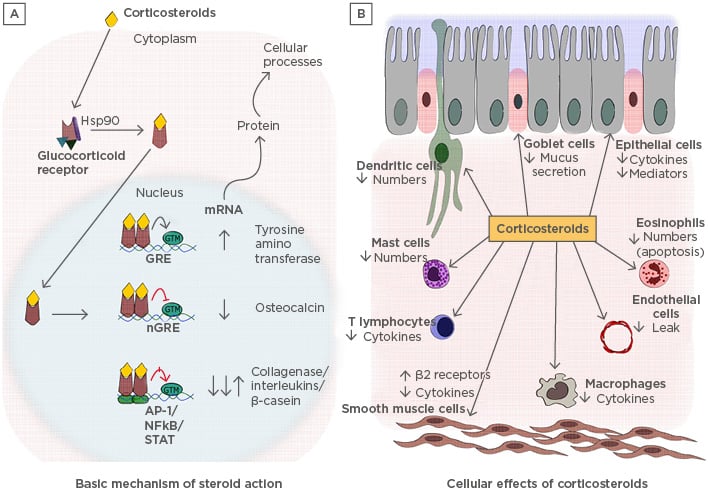

Endogenous GC participate in various physiological processes in a variety of cells, including hepatocytes, epithelial cells, neurons, immune cells, and cardiomyocytes (Figure 2). GC regulate multiple pathways, including carbohydrate metabolism, programmed cell death, amino acid metabolism, and inflammation.1 They have three basic modes of action: first, the binding of heterodimerised receptors to the GR element (GRE) in the target genes to activate the transcription; second, inhibition of target gene expression by binding of GR heterodimer onto the negative GRE (nGRE); third, transactivation or transrepression by physical interaction with other transcription factors.16 The GR bind with ligands and translocate into the nucleus. The GRα usually resides in the cytoplasm as part of a large multiprotein complex composed of chaperones such as Hsp90, Hsp70, p23, and immunophilin p59. These proteins bind to the unliganded GR and maintain its conformation in the cytoplasm without compromising the ligand binding efficiency.17 When the ligand binds to the receptor, the protein complex dissociates, causing a conformational change in the receptors and exposing the nuclear localisation signals. This leads to the translocation of the GR into the nucleus through nuclear pores.16

Figure 2: A) Basic mechanisms of steroid action and B) cellular effects of corticosteroids: pleiotropy in various cells.

A) The descriptive figure illustrates how glucocorticoids induce their effects in the cells. B) The cellular effects that are brought about in different types of cells due to the various gene regulations carried by corticosteroids.

AP-1: activator protein-1; GRE: glucocorticoid receptor element; GTM: general transcription material; Hsp90: heat shock protein 90.

Once GR enters the nucleus, the activated hormone-bound receptor dimerises and binds to the GRE via a zinc finger motif containing a DNA binding domain. Binding of GR to GRE leads to conformational changes in the receptor, which allow it to interact with several coactivators, such as cyclic adenosine monophosphate response element binding protein, p300, steroid receptor coactivator-1, p/CIF, SWI/SNF, and NcoA-1, which are critical in modulating the chromatin structure.2 These coactivators activate gene transcription by unwinding the chromatin structure. Corticosteroids suppress inflammatory responses by activating the expression of anti-inflammatory proteins such as annexin-1, secretory leukoprotease inhibitor, IL-10, and IκBα. To generate this response, a large steroid concentration is required, but in a clinical scenario, a very small dose of corticosteroids is enough to generate the anti-inflammatory response.18 Therefore, it is a controversial suggestion that the activation of genes would lead to the fruitful functioning of steroids. Hence, it is thought that an increase in transcription might generate systemic side effects, such as osteoporosis, growth retardation in children, skin fragility due to increased apoptosis, and metabolic effects observed due to overuse of steroids. To support this hypothesis, it was shown that mutant GR, which was unable to bind to GRE, did not show any loss of anti-inflammatory properties of steroids and was capable of suppressing NFκB-activated genes. This could also mean that GR has a different pathway of inhibiting NFκB-mediated inflammation19 (Figure 2).

At the promoter level, GR can also inhibit the expression of its target gene through nGRE.20 The inhibition in the transcription of genes takes place typically through two mechanisms; first, GR competes for its binding site on nGRE and hinders the binding of the other transcription factors, inhibiting the transcription of the downstream genes such as osteocalcin.21 The second mechanism is via composite GRE, wherein the GR dimer bound with nGRE interacts with adjacent transcription factors and results in either gene repression or activation, which is dependent on the subunit of the composition. nGRE have been identified in the promoters of genes encoding for glutathione S-transferase, insulin, and vasoactive intestinal polypeptide receptor 1.

The GR can also regulate the expression of genes independent of direct binding to GRE. The GR exerts its anti-inflammatory role mainly through interacting with other transcription factors, such as NFκB and AP-1, binding to each other via the leucine zipper interaction.23 NFκB is the master regulator of many proinflammatory cytokines and immune genes, and it seems intuitive that GR might reduce inflammation by inhibiting NFκB.24 Another indirect way that GR inhibits protein synthesis is by reducing the stability of RNA encoding granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF) and cyclo-oxygenases. The GR receptor also represses proteins of the MAPK family by inhibiting the phosphorylation essential for their activation.

The capability of GC to produce anti-inflammatory actions also stems from their ability to induce apoptosis in inflammatory cells, such as thymocytes, eosinophils, and monocytes, and provide protection against apoptotic stimuli in cells with non-lymphoid origin.25 GC have also been recently reported to inhibit mucus secretion in airways by repressing the expression of mucin genes such as MUC2 and MUC5AC.26 In addition, GC are efficient at reducing neurogenic inflammation by inhibiting the synthesis of tachykinins and tachykinin receptors, which amplify the inflammatory responses.27

MOLECULAR MECHANISMS OF STEROID RESISTANCE

With more than a decade of studies attempting to identify the molecular mechanisms of steroid resistance, a lot of pathways and mechanisms have been explored; however, there are four overarching steps that are essential in GC dysfunction: a) reduced GR expression, b) defective binding of steroids to the receptor, c) reduced ability of the receptor to bind to the DNA, either due to competition or reduced nuclear translocation, and d) increased expression and antagonism from proinflammatory transcription factors (AP-1 and NFκB).3 In addition, a number of other mechanisms, like increased GRβ expression, defective histone acetylation, and involvement of immune cells have also been demonstrated. Here, a few key mechanisms of steroid resistance are described.

Defective Glucocorticoid Receptor Binding and Nuclear Translocation

Reports indicate that cytokines such as IL-2, IL-4, and IL-13 are overexpressed in the airways of steroid-resistant asthma patients.3 In T cells and inflammatory cells, these cytokines are presumed to reduce GR affinity and elicit a local resistance to the anti-inflammatory action of GC.28 These cytokines reduce steroid functioning by preventing phosphorylation of the GR. Impairment in GR phosphorylation and subsequent impaired translocation of the receptor into the nucleus and reduced binding to GRE have been reported in large proportions of patients with steroid unresponsiveness. p38 mitogen activated protein kinase (p38MAPK) is thought to participate in the phosphorylation of GR, which does not allow for nuclear translocations, and this effect is blocked upon addition of a p38MAPK inhibitor.29,30 IL-2, IL-4, IL-5, and IL-13 are known to induce the phosphorylation of serine 226 on GR, which is inhibited by p38MAPK inhibitor. Selective inhibition of p38MAPK isoforms alpha, beta, and gamma increases the responsiveness to steroids in alveolar macrophages and peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) of severe asthma patients in response to IL-2 plus IL-4.31

TNF-α-induced p38MAPK, c-Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK), also phosphorylates GR at serine 226, inhibiting its binding with GRE in PBMC isolated from severe asthma patients.32 To combat the phosphorylation-induced inefficiency of GR, corticosteroids and long-acting β2 agonists (LABA), like formoterol, activate MKP-1 and protein phosphatase 2A (PP2A), endogenous inhibitors of the JNK and p38MAPK pathways.33 In alveolar macrophages of patients with a poor response to steroids, it was observed that MKP-1 expression was significantly reduced and was negatively corelated with p38MAPK activity. PP2A expression and activity was found to be reduced in PBMC of steroid-resistant asthma patients and knockdown of PP2A or inhibition reduced steroid responsiveness by inhibiting nuclear translocation and increasing JNK1 phosphorylation.

Inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS) has been reported to be increased in severe asthmatic patients, and high levels of nitric oxide have been reported to modify the GR ligand binding site by nitrosylating the GR at the Hsp90 interaction site, thereby inhibiting the translocation of GR into the nucleus. Whether this is relevant to steroid-resistant patients or not remains to be studied.28,34 Intriguingly, iNOS is increased by smoking,35 and steroid insensitivity in smokers with asthma may be attributed to this mechanism.

Increased Glucocorticoid Receptor-β Expression

The dominant negative isoform of GR, GRβ, has been described to be increased in the lymphocytes, neutrophils, and PBMC of steroid- resistant patients.36,37 As previously explained, GRβ is induced by proinflammatory cytokines and competes with GRα for the GRE, and hence it acts as a dominant negative inhibitor. GRβ also acts as a decoy receptor as it does not have any ligand binding sites.14 Microbial super antigens, such as Staphylococcal enterotoxins, also increase the expression of GRβ and this leads to steroid resistance in nasal explant models.37 Another possible mechanism was discovered in alveolar macrophages of steroid-resistant asthmatic patients, where knockdown of GRβ with siRNA resulted in GRα nuclear translocation and increased steroid responsiveness.37

Defective Histone Acetylation

In a different group of steroid-resistant asthmatic patients, compromised anti-inflammatory action of steroids was observed along with reduced side effects. This was attributed to the inability of GR to acetylate lysine residue (K5) and hence transactivation of genes, which is required both for anti-inflammatory action and side effects. Repression of gene expression is also mediated by recruitment of histone deacetylase 2 (HDAC2) to deacetylate the chromatin and cause structural changes. HDAC2 expression has been reported to be reduced in alveolar macrophages, airways, and peripheral lungs in patients with severe asthma and steroid resistance.38-40 The mechanism for this has been elucidated: oxidative and nitrative stress led to the formation of peroxynitrite, which nitrates tyrosine residues on HDAC2, resulting in ubiquitination, degradation, and inactivation of HDAC2. Oxidative stress also phosphorylates PI3Kδ, which further leads to phosphorylation and inactivation of HDAC2.40-42

Immune Mechanisms

Th17 cells have been shown to be the hallmark cell type as they not only increase in number but also induce neutrophilic inflammation in steroid-resistant patients. In mice, adoptive transfer of Th17 cells leads to steroid resistance. In addition to this, IL-17 increases the expression of GRβ in airway epithelial cells more than in other cell types and is not suppressed by corticosteroids in vitro. When Th17 is increased, Treg cell response is reduced as they fail to secrete IL-10 in response to steroids; however, it was recently shown that oral administration of vitamin D3 enhanced ex vivo Treg response to steroids.43 This suggests that vitamin D3 could be used as a potential therapeutic drug along with steroids.

Possible Therapeutic Strategies to Control Steroid-Resistant Asthma

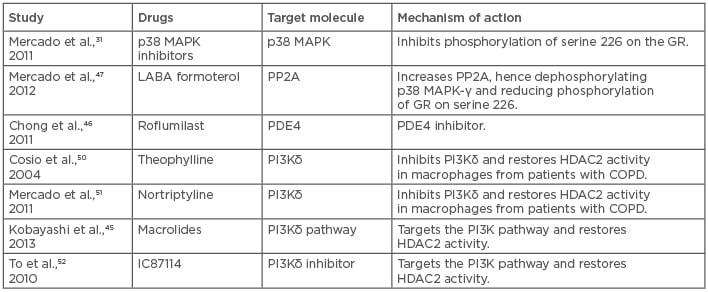

With the present studies and insight into the mechanism of action of steroids, many potential strategies have been identified to control steroid- resistant asthma. One of the most common strategies is the use of broad-spectrum antibiotics.44 This is due to the fact that most cases of neutrophilic asthma that are resistant to corticosteroids are because of bacterial infections.44 Interestingly, solithromycin, a novel macrolide, improved oxidative stress-mediated steroid insensitivity, and, when it was given along with steroids, also inhibited neutrophilia.45 In this respect, phosphodiesterase 4 inhibitors and oral roflumilast are in clinical development as an anti-inflammatory regimen; however, these oral uses are limited by their side effects, such as nausea, diarrhoea, and headaches, and inhaled drugs have proven ineffective so far.46 p38MAPK inhibitors look promising based on the theoretical and experimental studies in steroid-resistant asthma.31,47 However, in rheumatoid arthritis, prolonged administration of p38MAPK inhibitors led to the development of tolerance for the drug, suggesting that this might not be the only essential pathway.48 HDAC2 restoration with plasmid vectors has been reported to improve steroid responsiveness in macrophages of severe asthma patients, but administration of plasmids to patients does not seem clinically viable.49 In such a case, selective activation of HDAC2 could prove beneficial; drugs like theophylline and nortriptyline are known to increase HDAC2 expression and increase HDAC2 activity by inhibiting PI3Kδ.50-52 Similarly, sulforaphane and curcumin have been found to increase the expression of HDAC2 and reduce oxidative stress. Inhaled LABA are usually prescribed for asthmatics, and it is now well established that, when given alongside steroids, they improve the action of steroids by increasing the nuclear translocation of GR necessary for its anti-inflammatory actions. LABA achieves this by inhibiting the phosphorylation of GR at serine 226, inhibiting JNK1 and p38MAPKγ.53-55 This benefit is mutually shared as GR increases the expression of β2 agonist receptors, increasing receptor turnover and preventing receptor blunting3,30 (Table 1).

Table 1: List of possible drugs and novel therapeutic strategies for the treatment of steroid-resistant/severe asthma by interfering with the pathways that cause it.

COPD: chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; HDAC2: histone deacetylase 2; PDE4: phosphodiesterase type 4; PP2A: protein phosphatase 2A; GR: glucocorticoid receptor; p38 MAPK: p38 mitogen activated protein kinases.

CONCLUSION

Although quite a few therapeutic strategies have been identified, a more concrete approach is required that ensures the side effects are reduced. For instance, blocking pathways and proteins that might also play a role in basic cell homeostasis could prove to be futile and even dangerous. With this premise, one can think of therapeutic agents, such as vitamin D3, which have been shown to be beneficial. However, recent studies raise the concern that the function of vitamin D3 is ambiguous as it did not show any protective effects against upper respiratory tract infections in adults with asthma along with stable doses of corticosteroids.56,57 This indicates that any further complications in asthma, such as viral load, could alter the expected effect of vitamin D3. Not only vitamins but dietary supplements, such as omega-6 fatty acid, are also known to be correlated with asthma prevalence. Our group has shown that one such omega-6 fatty acid metabolite, 13-S-HODE, leads to severe asthmatic symptoms in mice and is resistant to steroid therapy.58 This study is also relevant as it has been shown that 13-hydroxyoctadecadienoic acid increases in the sera of asthmatics compared to controls. This indicates that 13-hydroxyoctadecadienoic acid is an intrinsic parameter that may lead to steroid resistance in asthmatics if left unchecked. Thus, dietary supplementation may also prove to be important in genesis of the steroid-resistant features in asthmatics. Keeping this in mind, it is essential to identify and study more pathways to give rise to a more promising therapeutic with minimal side effects. This can be done by developing efficient mice models and studying molecular mechanisms from a new point of view.