BACKGROUND AND AIMS

The burden of prediabetes appears to be increasing worldwide. According to the International Diabetes Federation (IDF), low and middle-income countries have the highest prevalence of prediabetes.1 If left untreated, individuals with prediabetes have an elevated risk of progressing to Type 2 diabetes mellitus. Thus, identifying prediabetes early may help to implement effective intervention strategies targeting diabetes prevention. While non-European populations have an increased risk of developing diabetes, it is unclear if trends in prediabetes incidence and prevalence over time differ according to ethnicity and age group.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Linked health, laboratory, and immigration data were used to identify adults aged 20–84 who immigrated to Ontario, Canada, who were free of diabetes. Data from hospital and commercial laboratories were used to identify individuals who underwent diabetes screening between 2011 and 2017. Prediabetes cases were defined using World Health Organization (WHO) criteria (fasting plasma glucose: 6.1–6.9 mmol/L, 2-hour plasma glucose: 7.8–11.0 mmol/L on a 75 g oral glucose tolerance test, or HbA1c: 6.0–6.4%). Immigrants were classified into distinct world region of origin based on validated algorithms using country of birth, mother tongue, and surnames. The authors used direct age and sex standardisation methods with 2011 Canadian census data to calculate prediabetes incidence over time among adults aged 20–34, 35–49, 50–64, and ≥ 65 years, across different ethnic origins.

RESULTS

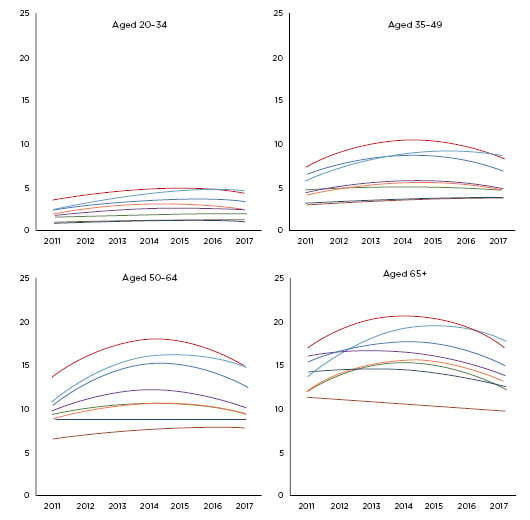

Overall, the prevalence and incidence of prediabetes in Canadian immigrants rose between 2011 and 2014, followed by a subsequent decline in 2017. The largest increases in the prevalence and incidence of prediabetes between 2011 and 2014 were observed among South Asian, Southeast Asian, and Sub-Saharan African/Caribbean populations. Over the 7-year period, the age-adjusted and sex-adjusted prevalence of prediabetes decreased only slightly from 20.0%, 17.0%, and 14.1% in 2011 (N=510,144) to 16.7%, 17.8%, and 13.8% in 2017 (N=600,437) among South Asians, Southeast Asians, and Sub-Saharan African/Caribbeans, respectively. Similar trends were observed for age-adjusted and sex-adjusted incidence of prediabetes across most non-European ethnic groups and ages (p<0.001). However, among European populations, prevalence and incidence of prediabetes only declined to a lesser degree over time. The incidence and prevalence of prediabetes rose sharply by age for immigrant populations across all ethnic groups. However, South Asians had the largest increases in prediabetes incidence by age. For instance, the incidence of prediabetes was highest among South Asians, ranging from 3.8 per 100 person-years at ages 20–34, 7.6 per 100 person-years at ages 35–49, 14.2 at ages 50–64, and 18.1 per 100 person-years at ages ≥ 65 years in 2011 (Figure 1). Similar observations were made for prevalence of prediabetes by ethnicity and age group over the study period (data not shown).

Figure 1: Age/sex standardised incidence of prediabetes (with 95% confidence intervals) between 2011 and 2017 among immigrants by ethnicity and age group.

*All lines based on line of best fit using a polynomial equation, R2>0.99 for each.

*Age-adjusted and sex-adjusted rates are directly standardised with the 2011 Canadian Census data.

*Ethnic groups were derived based on country of birth, mother tongue, and a validated algorithm that identifies ethnic groups based on surnames for South Asian and Chinese populations only.

DISCUSSION

The incidence and prevalence of prediabetes appears to be generally declining in Ontario among adults of different ethnicities and age groups, which may be attributed to screening and prevention practices, adoption of health promotion strategies, and other health care system interventions. We may also be observing an overall decline in diabetes risk factors or a combination of these factors in our population. Nonetheless, close surveillance and access to lifestyle interventions is important for reducing the burden of Type 2 diabetes mellitus in these high-risk populations. As well, further research is necessary to understand the trends of prediabetes prevalence and incidence among immigrants by ethnicity and age groups.