BACKGROUND

Infection with hepatitis C virus (HCV) increases the risk of extrahepatic manifestations, including cardiovascular disease (CVD).1 Cardiac magnetic resonance (CMR) remains the gold standard test for non-invasive structural and functional assessment of the heart, and can be used to detect CVD. Using CMR, the authors sought to determine the CVD risk in patients with HCV prior to therapy.2

METHODS

Individuals with chronic HCV infection were prospectively enrolled in the CHROME study (NCT03823911).3 A subset of 10 individuals infected with HCV were enrolled in the MRI sub-study from March–September 2019. HCV antibody assays, HCV RNA levels, liver fibrosis scores, and markers of inflammation and myocardial damage were obtained.

CMR was performed prior to the initiation of direct-acting antiviral treatment. Extracellular volume (ECV) fraction was calculated using the equation: ECV=100% x (1-hematocrit) x [(1/T1myocardium post-contrast) – (1/T1myocardium pre-contrast)]/[(1/T1blood post-contrast) – (1/T1 blood pre-contrast)]. An ECV fraction >30% was considered abnormally increased. Ten age-matched, HCV-negative volunteers were included in the analysis so that T-test was used to compare ECV fraction in both groups.

RESULTS

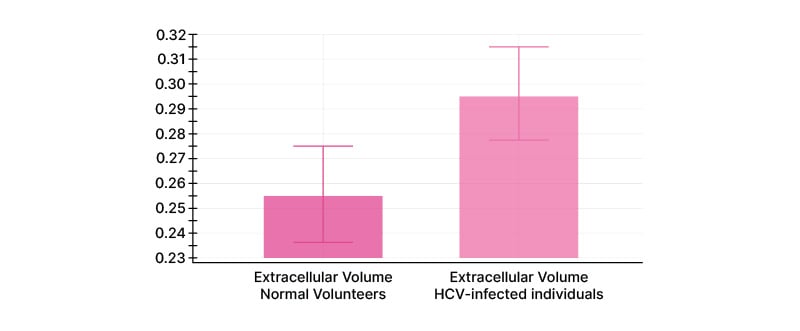

Demographics are shown in Table 1. CMR showed that 8/10 individuals infected with HCV had an abnormal ECV fraction (>30%;4 average=0.30; range 29–38%). When compared with age-matched healthy volunteers, ECV fraction in the individuals infected with HCV was significantly increased (0.30±0.03 versus 0.26±0.03; p=0.0036; Figure 1). Three of the 10 individuals infected with HCV had non-ischemic patterns of gadolinium enhancement on the late gadolinium enhancement images (Figure 2). For individuals infected with HCV, markers of inflammation and myocardial damage were within laboratory reference ranges for all subjects in the CMR cohort, and ECV fraction was elevated regardless of myocardial damage markers or liver fibrosis stage.

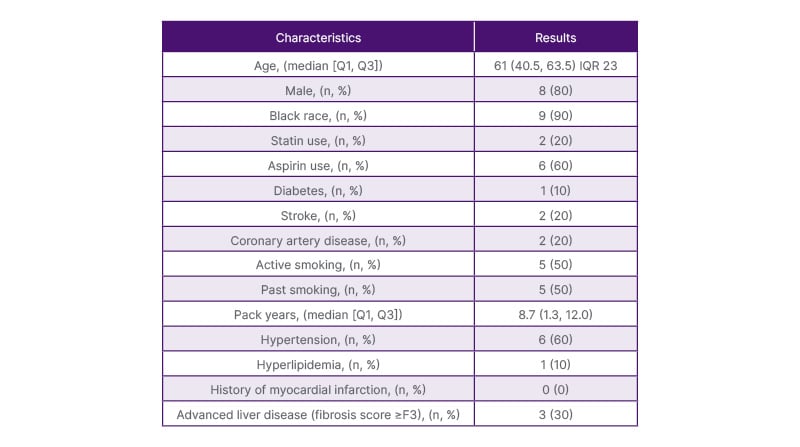

Table 1: Baseline demographic features of hepatitis C virus cardiac magnetic resonance cohort.

IQR: interquartile range.

Figure 1: Extracellular volume of individuals infected with hepatitis C virus and healthy volunteers.

Figure 2: Inflammatory changes seen on cardiac magnetic resonance in patient with hepatitis C.

A) Short axis late gadolinium enhancement image shows a midwall pattern of enhancement within the basal septal wall (arrow), compatible with an area of midwall fibrosis. B) Native T1 map, and C) Post-contrast T1 mapshow a corresponding area of abnormal T1 measurements within the basal septum (arrows).

CONCLUSIONS

The findings suggest that myocardial changes secondary to HCV infection can occur without measurable changes in inflammatory or myocardial biomarkers, and that ECV fraction via CMR may be a sensitive screening tool to detect these changes. This has important implications for the necessity of early HCV treatment, since cardiovascular changes can precede the development of advanced liver fibrosis in individuals infected with HCV.