Meeting Summary

Immunoglobulin A nephropathy (IgAN) is one of the most common forms of primary glomerulonephritis. In some patients, it can progress rapidly, leading to proteinuria, kidney failure, and death. Standard of care is traditionally with an angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitor (ACEi), or an angiotensin II (Ang II) receptor blocker (ARB). More recently, drugs targeting both endothelin 1 (ET-1) and Ang II receptors have been developed, as overactivation of such is implicated in IgAN. Sparsentan is a dual ET Type A (ETAR) and Ang II subtype 1 receptor (AT1R) antagonist. The PROTECT study compared sparsentan with the ARB irbesartan, in patients with IgAN and with proteinuria of ≥1 g/day despite stable dose of ACEi/ARB for ≥90 days. Data presented at the 2023 American Society of Nephrology (ASN) Kidney Week showed that use of sparsentan led to sustained (>110 weeks) decreases in proteinuria, and a significantly greater preservation of kidney function, compared with irbesartan. The ongoing SPARTAN study is investigating the use of sparsentan in recently diagnosed, treatment-naïve patients with IgAN. Preliminary data in 12 patients showed rapid and sustained proteinuria reductions, with little change from baseline in estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR), body weight, or total body water mean at Week 36. In both studies, sparsentan was generally well-tolerated with, in PROTECT, a comparable safety profile to irbesartan. Data presented at the congress also showed that sparsentan consistently occupies AT1R at levels exceeding ETAR occupancy. This balance is hypothesised to contribute to sparsentan’s limited risk of fluid retention.

Introduction

The immune complex-mediated glomerular disease IgAN is a predominant cause of primary glomerulonephritis,1-4 especially in males,5 with an incidence of 0.2–5.7 per 100,000 persons per year.2,3 IgAN is most commonly diagnosed in patients between 20–40 years of age.2,6,7 Initial presentation of IgAN can range from generally asymptomatic microscopic haematuria, to high levels of proteinuria, and from slow to rapid progression, to kidney decline and death.1,8 Analysis of 2,299 adults with IgAN from the UK National Registry of Rare Kidney Diseases (RaDaR) database found an estimated 5-year survival rate of 0.71 (95% confidence interval [CI]: 0.69–0.73) and 20-year survival rate of 0.28 (95% CI: 0.25–0.31).9

IgAN initially develops due to high circulating levels of galactose-deficient IgA1,10 which can occur following a mucosal infection, and is due to an inherited abnormality in some.11,12 Autoantigens can develop to galactose-deficient IgA1 and, in complex, these can be deposited in glomerular mesangium, leading to mesangial cell activation and ET-1 and Ang II overexpression, complement pathway activation, and inflammatory component secretion, proteinuria, glomerular injury, kidney inflammation, tubulointerstitial scarring, and fibrosis.1,12-14 ET-1 has a wide role in kidney function, including in fluid, sodium, and renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system homeostasis, as well as glomerular arteriolar and vascular tone regulation.15 Increased ET-1 renal expression is predictive of rapid IgAN progression,16 with sustained ETAR activation shown in progressive IgAN, associated with proteinuria, tubulointerstitial inflammation, and fibrosis.17 Ang II, via AT1R, has a role in intraglomerular pressure and cell growth, as well as in renal inflammation, vascular dysfunction, tubulointerstitial fibrosis, and proteinuria development.18,19 It can also stimulate renal release of, and enhanced vasoconstriction by, ET-1.18,20

IgAN treatment is key to slowing progression and increasing survival.21 According to the Kidney Disease Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) Glomerular Diseases Work Group, for patients with proteinuria >0.5 g/day, initial therapy is the highest tolerated dose of an ACEi or ARB. Optimised supportive care may include blood pressure management, strategies to reduce cardiovascular risks, and lifestyle modifications. For patients with proteinuria >0.75–1.00 g/day despite ≥90 days optimised supportive care, immunosuppressive drugs may be utilised, and/or patients may consider entering into a clinical trial, where appropriate. Treatment-emerged toxicity risks with immunosuppressive drugs must be considered in patients with eGFR <30 mL/min/1.73 m2, diabetes, a BMI >30 kg/m2, latent infections, secondary disease, uncontrolled psychiatric illness, severe osteoporosis, or active peptic ulceration.21

Sparsentan for the Treatment of IgAN

Analysis of the RaDaR data showed that, for patients with IgAN, higher proteinuria was significantly associated with worse kidney survival.9 As such, treatment includes drugs that can lower proteinuria.21 One such therapy is sparsentan, a novel, non-immunosuppressive, single-molecule, dual ETAR and AT1R antagonist (DEARA).18 This drug received a European Medicines Agency (EMA) orphan designation for IgAN,22 and accelerated approval by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA).23 Sparsentan’s action as a DEARA is key to its role in controlling IgAN.18

The PROTECT Study for Sparsentan

Sparsentan received accelerated FDA approval23 based on interim results from the double-blind, randomised PROTECT study (NCT03763850), which included the AT1R-only antagonist irbesartan as an active comparator.24 PROTECT included adults (≥18 years old) with biopsy-proven IgAN and, at screening, proteinuria of ≥1 g/day, and eGFR ≥30 mL/min/1.73 m2. Participants were on stable, maximally tolerated ACEi or ARB doses for ≥12 weeks prior to screening. The double-blind treatment period was 110 weeks, with the primary efficacy endpoint of change in urinary protein-to-creatinine ratio (UPCR) from baseline to Week 36. After 110 weeks, there was a 4-week study drug withdrawal period, and resumption of optimised supportive care.24

In total, 404 participants were randomised and treated with either sparsentan (200 mg/day initially, titrated to 400 mg/day from Week 3; n=202) or irbesartan (150 mg/day initially, titrated to 300 mg/day from Week 3; n=202). For both drugs, these are the maximum label doses.25,26 All participants discontinued ACEi/ARB treatment 1 day prior to study start. For the majority of participants, the study drug target dose was reached (sparsentan 95%, irbesartan 97%), with 17% of participants taking sparsentan and 11% taking irbesartan requiring dose reduction after reaching target. By Week 110, 19 participants discontinued sparsentan due to an adverse event (AE), and five due to participant decision. For irbesartan, 18 discontinued due to an AE, and 28 due to physician or participant decision.27

Mean age (±standard deviation [SD]) was similar between groups (sparsentan 46.6 years [±12.8] versus irbesartan 45.4 [±12.1] years), with both groups having a mean time of initial biopsy to informed consent of 4 years. Both groups had more males (sparsentan 69%, irbesartan 71%) than females, in line with epidemiology findings.5 The majority were White (sparsentan 64%, irbesartan 70%), or Asian (sparsentan 33%, irbesartan 24%). Groups had similar median (interquartile ranges) urine protein excretion values (sparsentan 1.8 g/day [1.2−2.9] versus irbesartan 1.8 g/day [1.3−2.6]), and mean eGFR (sparsentan 56.8 [±24.3] mL/min/1.73 m2 versus irbesartan 57.1 [±23.6] mL/min/1.73 m2), as well as similar blood pressure levels and haematuria occurrence.27,28

Results from the Phase III PROTECT Trial

Brad Rovin

In PROTECT,28 sparsentan significantly reduced UPCR by 49.8% from baseline to Week 36, compared with 15.1% for irbesartan (p<0.0001).29 As presented by Brad Rovin, Ohio State University Wexner Medical Center, Columbus, USA, and recently published, this reduction was sustained at Week 110 (Figure 1) when reductions from baseline were 42.8% with sparsentan, and 4.4% with irbesartan.27,28 A greater proportion of the sparsentan group (31%), compared with the irbesartan group (11%), achieved complete remission (<0.3 g/day; relative risk: 2.5 [95% CI: 1.6–4.1]).28

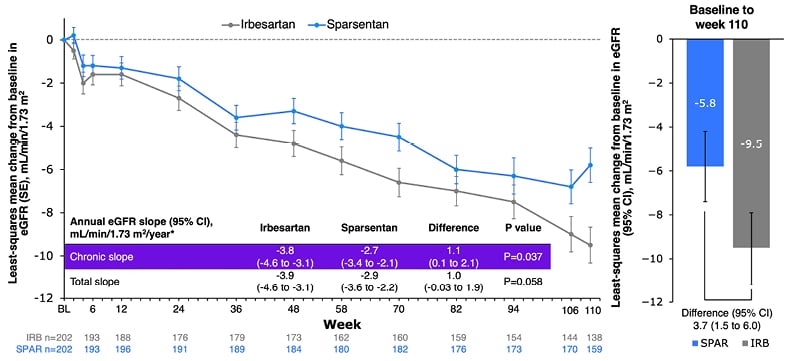

To ascertain whether changes in proteinuria translated into kidney function benefits, eGFR was also tracked over 110 weeks, with overall decline shown to be consistently lower with sparsentan than with irbesartan (Figure 1).27,28 A significant difference, favouring sparsentan, was shown in chronic slope (Weeks 6−110; p=0.037), with difference in total slope (Day 1−Week 110) narrowly missing significance (p=0.058; Figure 1).28

Figure 1: Change from baseline in estimated glomerular filtration rate.28

*Analysis includes eGFR data for patients on treatment; off-treatment and missing data imputed using the multiple imputation procedure.

CI: confidence intervals; eGFR: estimated glomerular filtration rate; SE: standard error.

Subgroup analyses of annualised change in eGFR by baseline eGFR (<60 or ≥60 mL/min/1.73 m2) or proteinuria (≤1.75 or >1.75 g/day) using the chronic or total slope demonstrated consistent treatment effects across disease severity. Sensitivity analyses of annualised change in eGFR (chronic or total slope models) included either the intention-to-treat population (all eGFR measurements to study end), or discounted eGFR measurements after initiation of rescue immunosuppression for renal disease (3% with sparsentan, 8% with irbesartan).28 These analyses also showed differences in favour of sparsentan. An additional finding was that 9% of the sparsentan group and 13% of the irbesartan group had a confirmed 40% reduction in eGFR, kidney failure, or death, with a relative risk for this composite kidney failure endpoint of 0.68 (95% CI: 0.4–1.2).27,28

Over 110 weeks, 93% of the sparsentan group and 88% of the irbesartan group reported a treatment-emergent AE (TEAE). The most common was COVID-19, followed by hyperkalaemia, peripheral oedema, dizziness, headache, hypotension, and hypertension. Percentages for each were similar between groups. There was a low, comparable incidence of elevated liver enzymes, and there were no cases of drug-induced liver injury. TEAEs led to treatment discontinuation in 10% of the sparsentan group and 9% of the irbesartan group. There was one TEAE leading to death, in the irbesartan group.27,28

Rovin concluded that the clinical benefit of sparsentan with regard to significant, rapid, and sustained proteinuria was confirmed by findings of significant differences in chronic eGFR slope between treatments, which they proposed to be an accurate measurement of the long-term nephroprotective effect of sparsentan and irbesartan. Sparsentan was generally well-tolerated, and the safety profile was comparable to irbesartan.27,28

Sparsentan Receptor Occupancy Modelling, Clinical Actions, and Safety Implications

Bruce Hendry

Two other findings in the PROTECT study were minimal changes in body weight in either group, and a low incidence of peripheral oedema (15% of the sparsentan group, 12% of the irbesartan group). Among participants with no oedema at baseline, 1% treated with sparsentan developed moderate oedema, and 1% treated with irbesartan developed severe oedema. New diuretic use was prescribed in 24% of the sparsentan group and 27% of the irbesartan group. No events of oedema led to sparsentan discontinuation, and there was no treatment-related fluid retention or heart failure.27 “These observations,” said Bruce Hendry, Travere Therapeutics, Inc., San Diego, California, USA, “are consistent with a benign safety profile of sparsentan in regard to fluid status.”

Hendry hypothesised that the action of sparsentan on maintaining normal fluid balance may be related to properties as a DEARA. IgAN mouse models show that blocking ETAR can lead to significant decreases in proteinuria and glomerulonephritis.31,32 However, use of drugs that target ETAR alone can lead to fluid retention, which, in some patients, has led to heart failure and hospitalisation.33 Conversely, AT1R antagonists can lead to decreased sodium retention and promote fluid excretion.34 Hence, with regard to fluid levels, the AT1R antagonist in sparsentan is proposed to balance the actions of the ETAR antagonist.19,29,35

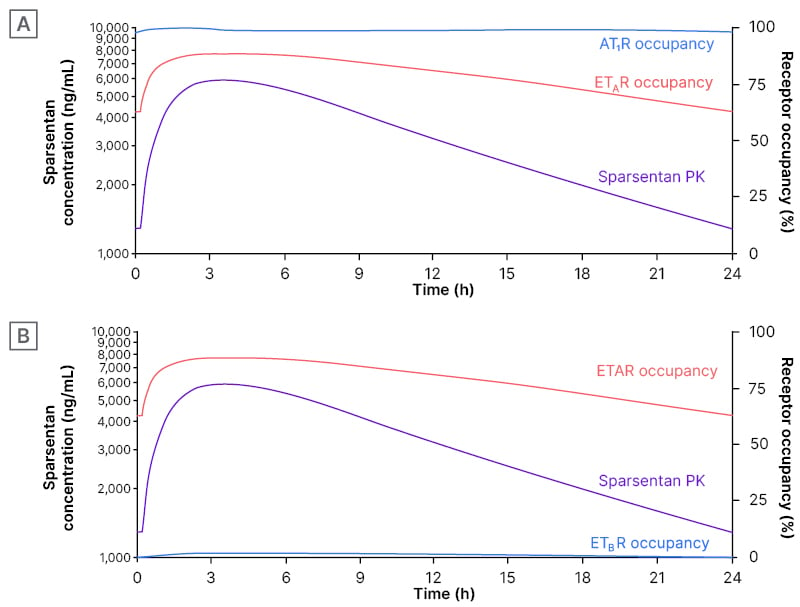

To examine the relationship between the clinical actions of sparsentan in IgAN, and its molecular, pharmacological properties, radioligand binding assays were used to determine 24-hour receptor affinities (inhibitory constant [Ki]) of sparsentan for ETAR, ETBR, AT1R, and AT2R, with population pharmacokinetic (PK) modelling used to derive 24-hour PK and receptor occupancy profiles. This utilised data from PROTECT participants.30

Steady-state PK parameters of sparsentan (Figure 2) included minimum/maximum plasma concentrations of 1,266/5,936 ng/mL, a half-life of 9.6 hours, and an area under the curve of 80,000 ng.h/mL. Receptor affinity (Ki) of sparsentan was highest for AT1R (0.36 nmol/L) and ETAR (12.8 nmol/L), and much lower for AT2R (190 nmol/L) and ETBR (6,582 nmol/L). Protein binding was 99%. “The data show that sparsentan creates a fully occupied AT1R throughout the 24 hours, at >0.95% occupancy,” said Hendry, “and substantial occupancy of the ETAR, varying between 60% and 90% that, importantly, is always less than AT1R occupancy. Occupancy of the ETBR is very low, <2%, and therefore, the selectivity for ETAR versus ETBR plays out as a clear effect in the clinical setting” (Figure 2).30 “When a drug solely targets ETAR, on top of AT1R blockade,” said Hendry, “periods of relatively unaccompanied ETAR antagonism may occur, representing a risk for fluid retention. If AT1R consistently exceeds ETAR antagonism, as seen with sparsentan, risk appears to be minimised or avoided.” The data shown here, continued Hendry, “are consistent with this hypothesis.” In summary, said Hendry, the results here “could partly explain the fluid retention seen with ETAR antagonists and the minimal changes in fluid status seen with sparsentan.”30

Figure 2: Sparsentan steady-state concentration (left axis)* and receptor occupancies (right axis) over 24 hours following administration of a single 400 mg oral dose in PROTECT.

A) AT1R and ETA B) ETAR and ETBR.30

*PK data are based on population PK model prediction for a patient with IgAN.

AT1R: angiotensin II receptor type 1; ETAR: endothelin receptor type A; ETBR: endothelin receptor type B; h: hours; IgAN: immunoglobulin A nephropathy; PK: pharmacokinetics.

Sparsentan as First-Line Treatment for Incident Patients with IgA Nephropathy: Preliminary Findings from the SPARTAN Trial

Chee Kay Cheung

In the RaDaR data analysis, survival rate was lowest, and mean eGFR slopes greatest, in patients with proteinuria ≥1.76 g/g. This was vice versa in those with proteinuria <0.44 g/g.9 As such, the actions of sparsentan on lowering proteinuria and eGFR slope shown above may, over time, lead to greater survival benefit.30 However, in PROTECT, the average time between diagnosis of IgAN and age at initial biopsy was around 4 years, with nearly one-third of participants receiving an ACEi or ARB at time of enrolment.27

Sparsentan’s rapid, sustained reduction in proteinuria, with corresponding nephroprotective properties,27,28 means it may be appropriate for newly diagnosed patients. The ongoing SPARTAN study (NCT04663204), a Phase II, open-label, single-arm trial, is investigating the safety, efficacy, and mechanistic actions of sparsentan as first-line therapy for patients with IgAN.37 Participants receive sparsentan 200 mg for the first 2 weeks, up-titrated to 400 mg, which they receive until Week 110, followed by a 4-week off treatment period. Key eligibility criteria include age ≥18 years, biopsy-proven diagnosis of IgAN within ≤6 months, proteinuria ≥0.5 g/day, eGFR ≥30 mL/min/1.73 m2, and no ACEIs/ARBs within ≤12 months. Key endpoints are change from baseline in proteinuria, eGFR, and blood pressure; complete remission of proteinuria (<0.3 g/day); and safety.37

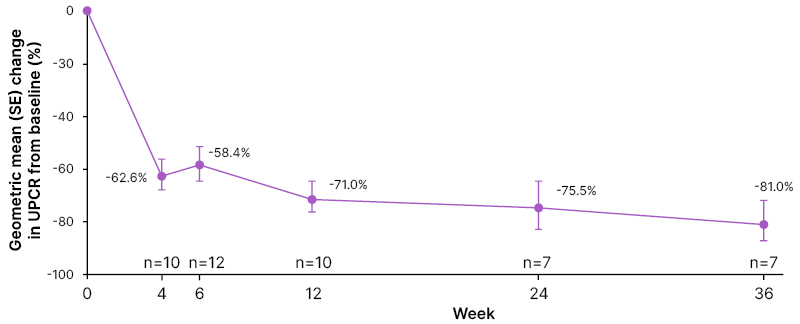

Chee Kay Cheung, University of Leicester, UK, reported preliminary clinical findings to Week 36 of SPARTAN for 12 participants, seven of whom were male (58.3%), 10 (83.3%) were White, and the mean age at informed consent was 35.8 years (±12.2). At data cutoff (September 26th 2023), seven participants had received sparsentan for 36 weeks, three for 12 weeks, and two for 6 weeks.36 At baseline, median (interquartile range) urine protein excretion rate was 1.4 g/day (0.6–3.2), and median UPCR was 1.3 g/g (0.4–1.7).36 Similar to PROTECT findings,27 following sparsentan initiation, UPCR decreased rapidly by Week 4, with reductions sustained over 36 weeks (Figure 3).36 Cheung reported how, “at baseline, four patients had protein excretion >2 g/day, three of which had proteinuria reductions of more than 75% during treatment. Overall, 67% achieved complete remission of proteinuria at any timepoint during the first 36 weeks.”

Figure 3: Proteinuria change (urine protein-to-creatinine ratio) from baseline.

SE: standard error; UPCR: urine protein-to-creatinine ratio.

Also shown in this analysis were relatively stable eGFR levels (baseline mean: 70.2 mL/min/1.732 [±25.0]) over 36 weeks.36 Mean systolic/diastolic blood pressure (125 [±10]/78 [±10] at baseline) decreased slightly until Week 4, but then remained stable (mean 114/70 at Week 36, SD not reported). Mean office and ambulatory 24-hour blood pressures also showed a systolic/diastolic decrease from baseline to Week 6: −12 mmHg (±8)/−7 mmHg (±8), −13 mmHg (±13)/−10 mmHg (±9), respectively. At baseline, mean BMI was 27.5 kg/m2 (±7.2), and weight was 83.1 kg (±24.7). The latter fluctuated mildly over 36 weeks, with mean changes ranging from −0.3 kg (±0.7) to 0.8 kg (±3.0). Total body water mean was 47.1 L (±7.4) at baseline. At Weeks 6, 12, and 14, this decreased slightly by −2.0 L (±7.2), −1.9 L (±7.9), and −3.6 L (±9.1), respectively.36 One participant discontinued after 6 weeks’ treatment due to hypotension. There were three serious AEs, none of which were treatment-related.36

Cheung concluded that “as first-line treatment in patients newly diagnosed with IgAN, sparsentan led to a rapid and sustained reduction in proteinuria and control of blood pressure, and was generally well-tolerated. Body weight was maintained, with no evidence of fluid retention.”36 These initial findings are similar to those shown in PROTECT.27 Of note, this was a treatment-naïve population.36 As higher proteinuria levels at diagnosis and over time are associated with worse survival and kidney failure outcomes,9 lowering proteinuria early following diagnosis could contribute to better outcomes.

Conclusion

IgAN can, in some patients, progress rapidly to kidney failure or death; hence, effective treatment is key to preserving kidney function and sustain survival.1,8,38 The strong antiproteinuric effects of sparsentan shown in PROTECT27 and SPARTAN36 arise, according to Hendry, from the properties of sparsentan as a DEARA.35,39 There is also evidence to suggest that minimal to no rates of clinically relevant fluid retention observed with sparsentan may be due to consistent occupancy of AT1R at levels always exceeding ETAR occupancy.27,30,36 The PROTECT27 and SPARTAN36 trials show the utility of sparsentan in both treatment-experienced and treatment-naïve patients, with regard to both sustained proteinuria decreases and renal protection. Sparsentan was generally safe and well-tolerated.