Meeting Summary

Antimicrobial resistance (AMR) has increased substantially among community-acquired uropathogens that cause urinary tract infections (UTI), limiting the availability of effective oral antibiotic treatments.

This review includes coverage of an expert-led Learning Lounge, symposium session, and several poster presentations, that took place between 20th–22nd October 2022 as part of IDWeek2022 in Washington, D.C., USA.

An immersive Learning Lounge, sponsored by GSK, opened with Keith Kaye, Department of Medicine, Rutgers–Robert Wood Johnson Medical School, New Brunswick, New Jersey, USA, who illuminated the concerns of AMR in community-acquired UTIs, delivering contemporary surveillance data, and outlined how in vitro data may translate into practical advice. This led fittingly to Erin McCreary, Division of Infectious Diseases, Department of Medicine, University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine, Pennsylvania, USA, who enquired whether enough is being done in clinical practice regarding community-acquired infections, highlighting the importance of antimicrobial stewardship (AMS), and galvanising the audience to adapt healthcare settings to the changing landscape.

The scientific programme also included three data-rich posters that showcased Kaye’s surveillance data on Escherichia coli and Klebsiella pneumoniae co-resistance, along with the geographical distribution of K. pneumoniae. An insightful poster by Claire Trennery, Value Evidence Outcomes, GSK, Brentford, UK, considered the patient perspective of UTI symptoms in defining antibiotic treatment success, and two posters presented by Rodrigo Mendes, JMI Laboratories, North Liberty, Iowa, USA, examined in vitro global surveillance data of emerging antimicrobial treatments.

Introduction

Community-acquired UTIs are associated with infections arising in community settings, and are categorised in patients who attend primary care settings such as an outpatient clinic or the emergency department without being admitted.1,2

In recent years, there has been a notable increase in AMR and multi-drug resistance (MDR) among community-acquired uropathogens causing UTIs, predominantly associated with E. coli,3-5 and K. pneumoniae.6-8 The number of effective oral treatments limited by AMR is of growing concern.9 Organisations such as the World Health Organization (WHO) and Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) in the USA prioritise several critical drug-resistant pathogens for new antibiotic treatments, including carbapenem-resistant, third-generation cephalosporin-resistant, and extended-spectrum β-lactamase (ESBL)-producing Enterobacterales.10-12

This congress review describes the epidemiology of AMR in community-acquired UTIs, the importance of AMS, and the emergence of prospective antimicrobial treatments.

Antimicrobial Resistance in Community-Acquired Urinary Tract Infections: Are We Doing Enough in Practice?

Keith Kaye and Erin McCreary

An interactive GSK-sponsored ‘Learning Lounge’ educational session, attended by a range of healthcare professionals, opened with Kaye highlighting the concerns of AMR in the community setting and positing the question: “What is the issue and why should we care?” He positioned this with an audience polling question: “Do you believe antimicrobial resistance is currently an increasing problem in community-acquired infections?” Despite respondents acknowledging AMR as a public health issue, several respondents did not believe the issue concerned them in their practice.

The Global Surveillance of Antimicrobial Resistance in Community-Acquired Urinary Tract Infections

Until recently, little was known about AMR prevalence in community-acquired UTIs due to limited public health surveillance data.13 Treatment approaches for UTIs often use empiric antibiotic therapy, where requests for urine cultures are low (approximately equal to 17% of patient cases),14 as they are not routinely recommended.

An increase in community-associated ESBL-related infections was seen between 2012–2017,12 and according to CDC data,11 major pathogenic threats are ESBL-producing Enterobacterales. Kaye stated this was “driven primarily, almost exclusively, by E. coli in the CTX-M ESBL, which has become the single-most common ESBL in the world in a very short period.”

Kaye identified that regardless of global location, AMR of community-acquired E. coli isolates is of concern, particularly for fluoroquinolones (FQ) and trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazoles (TMP-SMX).15-21

A study of community-acquired urinary E. coli isolates identified an elevated and persistently prevalent AMR to commonly prescribed antimicrobials, with 25.4% to TMP-SMX and 21.1% to FQ. Of the isolates, 6.4% were ESBL-positive (+), and 14.4% had ≥2 drug-resistant phenotypes.22 Likewise, Kaye emphasised the disconcerting increase in AMR among K. pneumoniae urine-isolates, with high resistance to β-lactams (>80%), nitrofurantoin (NFT; >50%), TMP-SMX (11.3%), FQ (6.8%), and 7.2% ESBL-producing phenotype.15

Kaye stipulated that raising awareness of current regional patterns of non-susceptible E. coli and K. pneumoniae isolates from community-acquired UTIs is important for guiding physicians empiric treatment decisions, and demonstrates the need for AMS efforts and use of appropriate surveillance data in community settings.

The Rising Prevalence of Co-Resistance in Community-Acquired Urinary Tract Infections

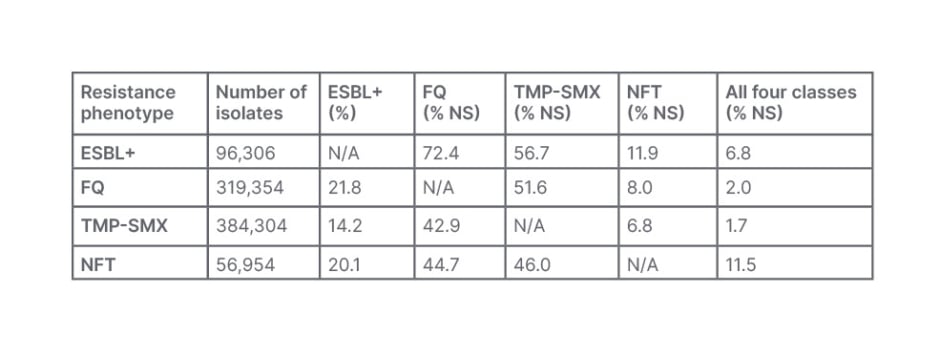

Considering co-resistance in community-acquired UTIs, Kaye referred to surveillance data, showcasing two data-rich posters. Co-resistance was defined as the presence of two or more of the four resistance phenotypes assessed (ESBL+, FQs, NFT, and TMP-SMX).

These surveillance datasets indicated a high prevalence of co-resistance in E. coli,23 and K. pneumoniae isolates.24 For E. coli, this was particularly towards ESBL+ isolates where 6.4% were ESBL+; while 21.1% were not susceptible to FQ, 25.4% to TMP-SMX, and 3.7% to NFT, with co-resistance to FQ (>70%) and 6.8% co-resistant to all four phenotypes observed (Table 1).23

Table 1: Co-resistant phenotypes in community-acquired Escherichia coli urine cultures from females aged ≥12 years, taken in 2011–2019 in the USA.23

ESBL+: extended-spectrum β-lactamase-positive; FQ: fluoroquinolone; NFT: nitrofurantoin; N/A: not applicable; NS: not-susceptible; TMP-SMX: trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole.

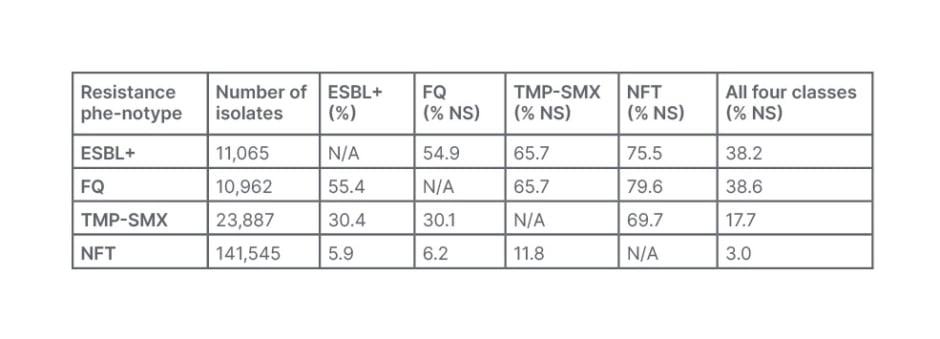

For K. pneumoniae, similar trends were shown, with co-resistance towards NFT (70–80% of isolates).24 Of the isolates, 4.4% were ESBL+; while 4.4% were not-susceptible to FQ, 9.5% to TMP-SMX, 56.5% to NFT, and 38.2% were co-resistant to all four phenotypes (Table 2).24

Table 2: Co-resistant phenotypes in community-acquired Klebsiella pneumoniae urine cultures from females aged ≥12 years, taken in 2011–2019 in the USA.24

ESBL+: extended-spectrum β-lactamase-positive; FQ: fluoroquinolone; NFT: nitrofurantoin; N/A: not applicable; NS: not-susceptible; TMP-SMX: trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole.

As affirmed by Kaye, these findings indicate limited effective oral antibiotic treatment options for community-acquired UTIs and emphasise the need for ongoing surveillance and improved clinician awareness of current AMR patterns to help inform appropriate empiric prescribing practices.23

Furthering this work, Kaye presented another poster regarding K. pneumoniae isolates, where the prevalence of all phenotypes increased over time, except NFT, which declined by 0.3%.25 Overall, ESBL+ increased 4.6%, and the prevalence of resistance was highest for NFT (56.6%), followed by TMP-SMX (9.6%) and FQ (4.4%), with trends of increasing resistance seen in older patients.25

Kaye emphasised the need for appropriate antibiotic prescribing, demonstrating treatment failure in 34.3% of patients (n=5,395) treated empirically with an antibiotic to which the pathogen was not susceptible.26 Treatment with FQ in non-susceptible isolates resulted in 36% re-prescriptions (or additional antibiotic prescriptions), and a two-fold increase (17%) in hospitalisation, compared to treatment of a susceptible pathogen.26

Kaye concluded that AMR in community-acquired UTIs is likely to get worse, and that healthcare professionals should pay more attention to the importance of AMR and AMS.

Implications for Rising Antimicrobial Resistance and Implementing Antimicrobial Stewardship

Continuing the Learning Lounge session, McCreary proceeded with a discussion addressing this global health priority through the role of AMS. With passion for this issue, McCreary discussed the importance of shifting focus to the community setting, with a focus on risk factors for non-susceptible pathogens.

The biggest risk factors for AMR in community-acquired UTIs include being over 55 years, residing in a nursing home, or being bedridden. Other risk factors include having a history of recurrent UTIs, multiple medical comorbidities, multiple hospitalisations, and antibiotic exposures.13,27,28 Those with UTIs caused by drug-resistant pathogens may often have a urinary catheter or neurogenic bladder.29,30

McCreary presented an interesting insight, that AMR transmission is greatest in the community setting, such as residential care31-33 and household transmission.34,35 A lack of community-based AMS programmes results in less controlled antibiotic use, supporting the notion of Kaye that efforts to decrease the spread of AMR are clinically important.36

Ambassadors of Antimicrobial Stewardship in the Community

In 2019, the Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA) guidelines affirmed that AMR was driven by unnecessary antibiotic use, and that community stewardship initiatives should tackle this.37

McCreary expressed the importance of not treating asymptomatic bacteriuria or non-specific symptoms with antibiotics, asking “are we causing harm to patients in the community [such as those presenting only with altered mental status] if we do not give them an antibiotic?” The ImpresU study38,39 highlighted that reducing antibiotic prescriptions in frail elderly patients by recommending a watchful waiting strategy over antibiotic prescriptions had no impact on secondary outcomes (complications, hospitalisations, mortality rate), but was able to significantly decrease antibiotic exposure.

McCreary also stipulated that for patients with legitimate infections, selecting an appropriate first-line empirical antibiotic with in vitro activity against the causative pathogen as soon as possible is important.29,40 McCreary also emphasised the use of local antimicrobial susceptibility rates, as highlighted by Kaye, when determining the appropriate empiric agent for one’s practice. McCreary extended this by referring to a UK-based primary care study that found 85.7% of UTI cases had received a prescribed antibiotic on the day of diagnosis, with 4.1% receiving a re-prescription for the same UTI episode.41 Thus, over 4 years, approximately 20,000 patients had received a second antibiotic due to failure to appropriately treat the infection empirically.41

McCreary also reminded the audience of the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) warning to avoid FQ42,43 due to highly-prevalent E. coli resistance in community-acquired upper UTIs (uUTI), and more toxicities compared to other antimicrobial classes authorised for the treatment of uUTI. Following this warning,42,43 FQ prescribing has significantly reduced (19.2% versus >40% prior), yet approximately one in five prescribers still recommend FQs first-line, signifying the ongoing need for AMS in the community.44

The Springboard for Antimicrobial Stewardship – Taking Responsibility

Antibiotic stewardship was making good progress until the COVID-19 pandemic, which led to a shifting of stewardship resources to pandemic response, resulting in more indiscriminate antimicrobial use in hospitals, an increase of ESBLs during hospitalisation, and more community-prescribed azithromycin, indicating a heightened threat to AMR.45

McCreary recapped a survey of general care community practitioners based in the USA (n=1,550), which elucidated most community providers acknowledged the importance of AMR (94%), but that only around half (55%) recognise the issue as their problem.46

The majority of the providers (93%) identified that inappropriate outpatient prescribing accelerates the emergence of AMR, yet only 37% identified that the problem exists in their own practice.46 When it came to taking responsibility for AMR in the community, most (91%) recognised that inappropriate outpatient prescribing was a problem, yet 60% felt that they prescribed antibiotics more appropriately than their peers.46 Lastly, despite 72% supporting the use of AMS programmes to address AMR, over half (53%) believed all they needed to do was talk with patients about the value of an antibiotic for their symptoms.46

McCreary concluded that there is a communal need for AMS ambassadors to educate and engage all healthcare practitioners in taking responsibility to decrease the spread of AMR in community-acquired UTI.46

The Learning Lounge highlighted the importance of surveillance data to drive decision-making in clinical practice, where outcomes data is crucial for demonstrating improved practice. Finally, community stewardship to address rising AMR in the community setting requires regional approaches, including public health campaigns to educate practitioners and patients to decrease antibiotic use.

POSTER PRESENTATIONS

Patient Experiences of Urinary Tract Infection: The Expectation of Complete Symptom Resolution

Claire Trennery

Determining UTI antibiotic treatment success requires assessing microbiological and clinical resolution (i.e., the complete resolution of symptoms [dysuria, urinary frequency, urinary urgency, and suprapubic pain]).47,48 However, the meaningfulness, and definition of treatment success, is rarely explored from the perspective of the patient experience.

A poster presented by Trennery, which garnered a lot of interest, determined what antibiotic treatment success meant to patients.49 The cross-sectional study conducted interviews with females with a confirmed uUTI diagnosis.49 Before treatment, the most common symptoms were urinary urgency (97%), retention (87%), frequency (83%), and dysuria (80%). Nearly all (97%) reported that the uUTI had impacted their mood or emotions, describing feelings of sadness, irritability, and aggravation.49

Almost all (90%) defined treatment success as when they no longer experienced any clinical symptoms by the end of the treatment period. Most (80%) scored each symptom as ‘none’ (zero), and reported this was meaningful or important.49 Participants who felt their treatment was successful reported that their day-to-day lives returned to normal.

These findings indicate patients experience a range of UTI symptoms that impact their quality of life. This insightful work supports the need to include complete clinical resolution endpoints, as well as valid scales of assessment in regulatory guidelines.

Emerging Antimicrobials for Community-Acquired Urinary Tract Infections

Rodrigo Mendes

With the continued threat of E. coli resistance and MDR in community-acquired UTIs, an alternative urgent treatment is required. Mendes presented a poster that garnered interest on in vitro data of emerging prospective antimicrobial treatments.

The study investigated the activity of oral antibiotics against E. coli subsets from community-acquired UTIs which observed high rates not susceptible to commonly used oral agents (e.g., FQs and TMP-SMX).50 A presumptive ESBL phenotype further compromised the activity of oral agents, including oral cephalosporins.

This data supports the need for further clinical development of novel antibiotic therapies as a treatment option for uUTIs caused by E. coli, including resistant isolates against which other oral treatment options are limited.

CONCLUSION

Across IDWeek2022 the fight against AMR in community-acquired UTIs was highlighted. Reflecting on the impact of surveillance data, a key recommendation was advocating community-based AMS, and fulfilling the patients’ desire for clinical resolution. Additionally, the development of new antimicrobial treatments has promise, but responsibility for appropriate empiric treatment decisions is needed at the practitioner level.