TODAY, the average American is twice as likely to be diagnosed with knee osteoarthritis than in the years leading up to World War II, according to a study by Dr Ian Wallace and Prof Daniel Lieberman, Harvard University, Cambridge, Massachusetts, USA. Research was carried out on the largest sample ever studied of older-aged individuals from three historic time periods.

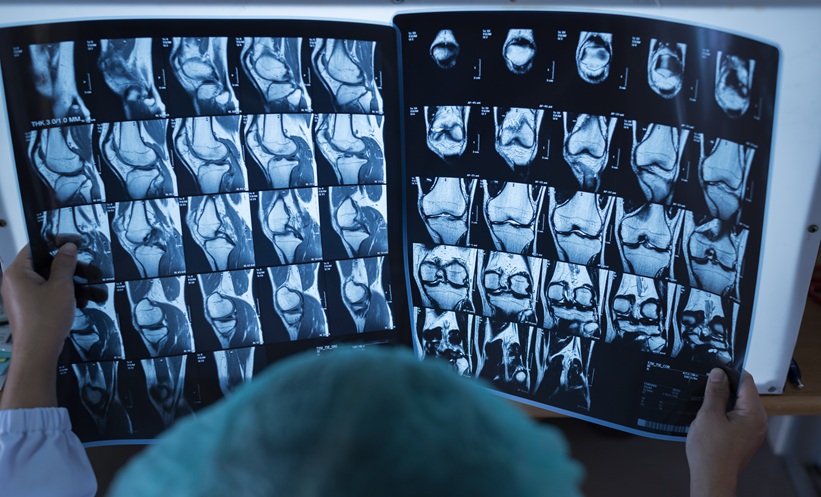

The authors examined >2,000 skeletons from >6,000 years of human history to search for tell-tale signs of osteoarthritis to understand the historical presence of the disease and whether incidence is on the rise. Dr Wallace explained: “When your cartilage erodes away, and two bones that comprise the joint come into direct contact, they rub against each other causing a glass-like polish to develop. That polish, called eburnation, is so clear and obvious that we can use it to very accurately diagnose osteoarthritis in skeletal remains.”

The most important comparison of data collected was between the early industrial and modern samples. More information could be gathered about individual samples at this time because data were available regarding age, sex, body weight, ethnicity, and occupation. After statistical analysis, taking into account all varying factors, the study concluded that individuals born after World War II have approximately twice the likelihood of developing osteoarthritis at specific ages or body weight, compared to individuals born before the war.

Previously, it was believed that knee osteoarthritis is a wear-and-tear disease and thus its frequency was increasing because people are living longer and are more commonly overweight or obese. However, this new study challenges that notion. It not only showed that the condition is twice as common today as it was in recent history, but, as Dr Wallace explained: “the even bigger surprise is that it is not just because people are living longer or getting fatter, but for other reasons likely related to our modern environments.”

Dr Wallace and Prof Lieberman hope these new data will enable researchers to now focus on what environmental changes there have been post-World War II and how they may contribute to the condition, which could lead to new prevention strategies. “Our society is barely focussing on prevention in any way, shape, or form, so we need to redirect more interest towards preventing this and other so-called diseases of ageingconcluded Prof Lieberman.

(Image: freeimages.com)